Leonard Pierce | September 4, 2025

Dutch cartoonist Erik Kriek has been mining a narrow but rich vein of comics over the last few years that places him in the same cultural space as certain film directors who do not choose to cast their nets wide or their sights exceptionally high, but rather chisel away at the same basic shapes, refining them, creating works in which the differences are minor but nevertheless are where the excellence of their labor resides. His latest effort, The Pit, can be read as the final installment of a dramaturgical triad that began with his folky backwoods murder ballad In the Pines and continued with the bloody, guilt-soaked Viking adventure The Exile.

Set in the Netherlands in the present day, The Pit introduces us to Hugh Pittman, a successful architect, and his wife Sara, an artist. A haut-bourgeois couple who move in sophisticated bohemian circles, their lives hang under the shadow of the loss of their only child, Ruben, who was killed by a passing truck. I've had people with children tell me that the death of a child in fiction is their only artistic trigger, and it's easy to understand why; almost any horror can be imagined except the notion of outliving a child you brought into the world. It's curious how this sort of accident is so common in fiction, but it lacks the savageness of a death by crime and the lingering heartbreak and injustice of a death by illness. It's no one's fault, really, and it's sudden and violent without seeming evil. But it nonetheless has strained their marriage, their work, and their lives.

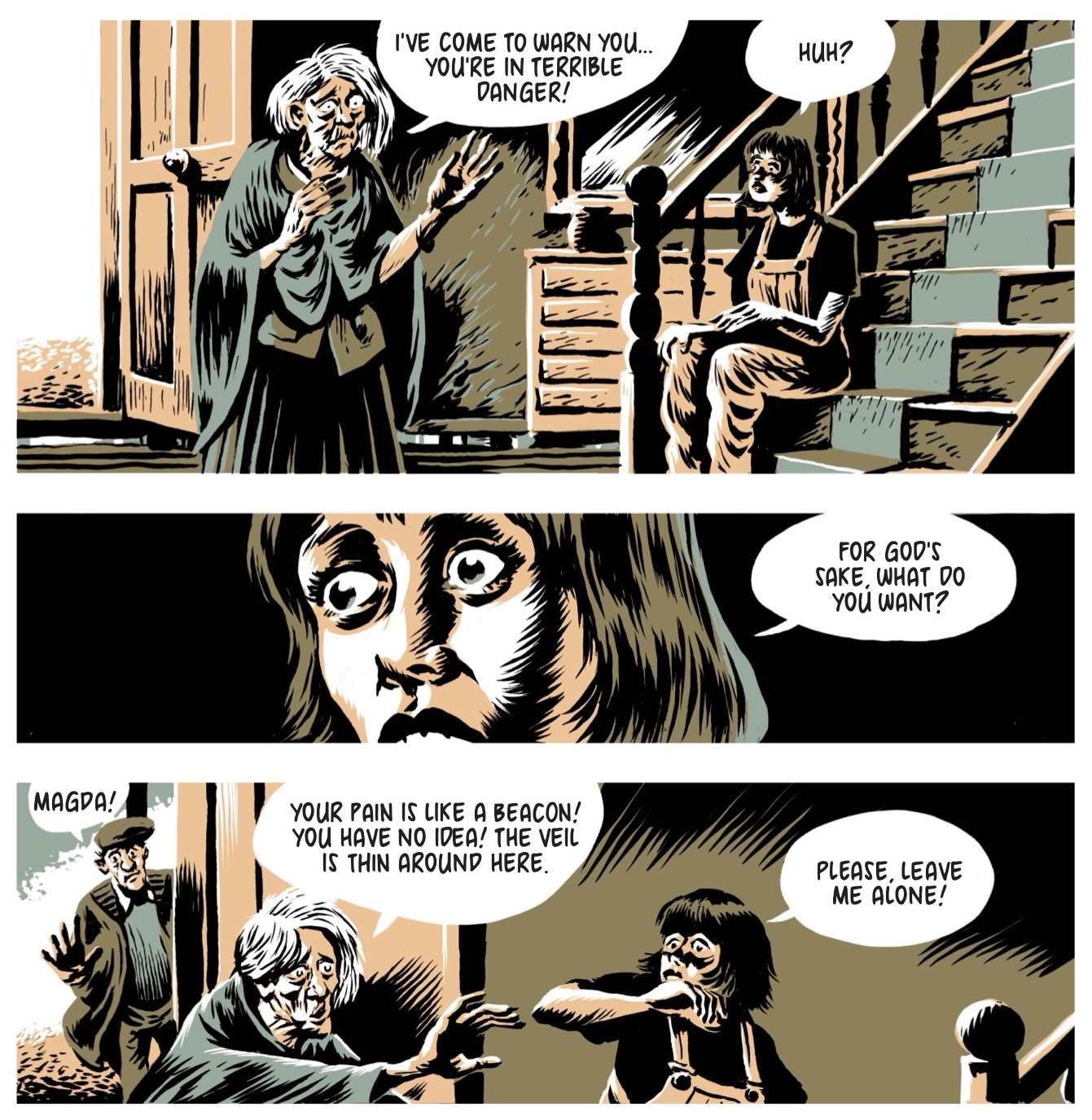

A sliver of hope appears, however, when a well-off relative of Hugh's passes away and leaves them a spacious, well-equipped house in an exurban part of the countryside. Hugh might get the chance to advance at work, Sara may finally get the peace she needs to start painting again, and the two of them could repair their broken marriage (though some conversations, full of recrimination and doubt, indicate that it may not have been on much sounder footing when young Ruben was alive). The place is isolated, spooky, and filled with ominous signs that are almost a little too much on the money, including some eerie carvings on the trees (“Someone's playing Blair Witch out here,” Hugh notes unnecessarily) and the requisite crazy old lady from the village who sees what others can't.

There's nothing particularly unique or unprecedented in what happens next. Old wrongs are unearthed, ancient texts are discovered, dreams are disturbed by frightening portents, and domestic bliss is gained only to be shattered. It's not the originality of the story that draws readers in to the world that Kriek lays out; it's at the craft and skill with which it's accomplished. We've seen this story before, but we've not often seen it told with the precision and care we see in The Pit; it's the difference between a visionary tyro and a dedicated professional, and that's a difference we should see highlighted more often.

The dialogue and story here are well-assayed, but neither are particular stellar; the storytelling is well above average for a horror comic, but isn't particularly transcendent, and the dialogue simply communicates information and mood without frills or embellishment, and doesn't leave much behind that might be memorable. But it's in the silences that The Pit's scares really work: the insinuations that tell more than we get out of the exposition, the quick and economical jump-scares and facial expressions that sell the tone as well as any good folk-horror film, and the increasingly disturbing quality of the art — both in the book itself and in Sara's work — that builds tension until the inevitable end.

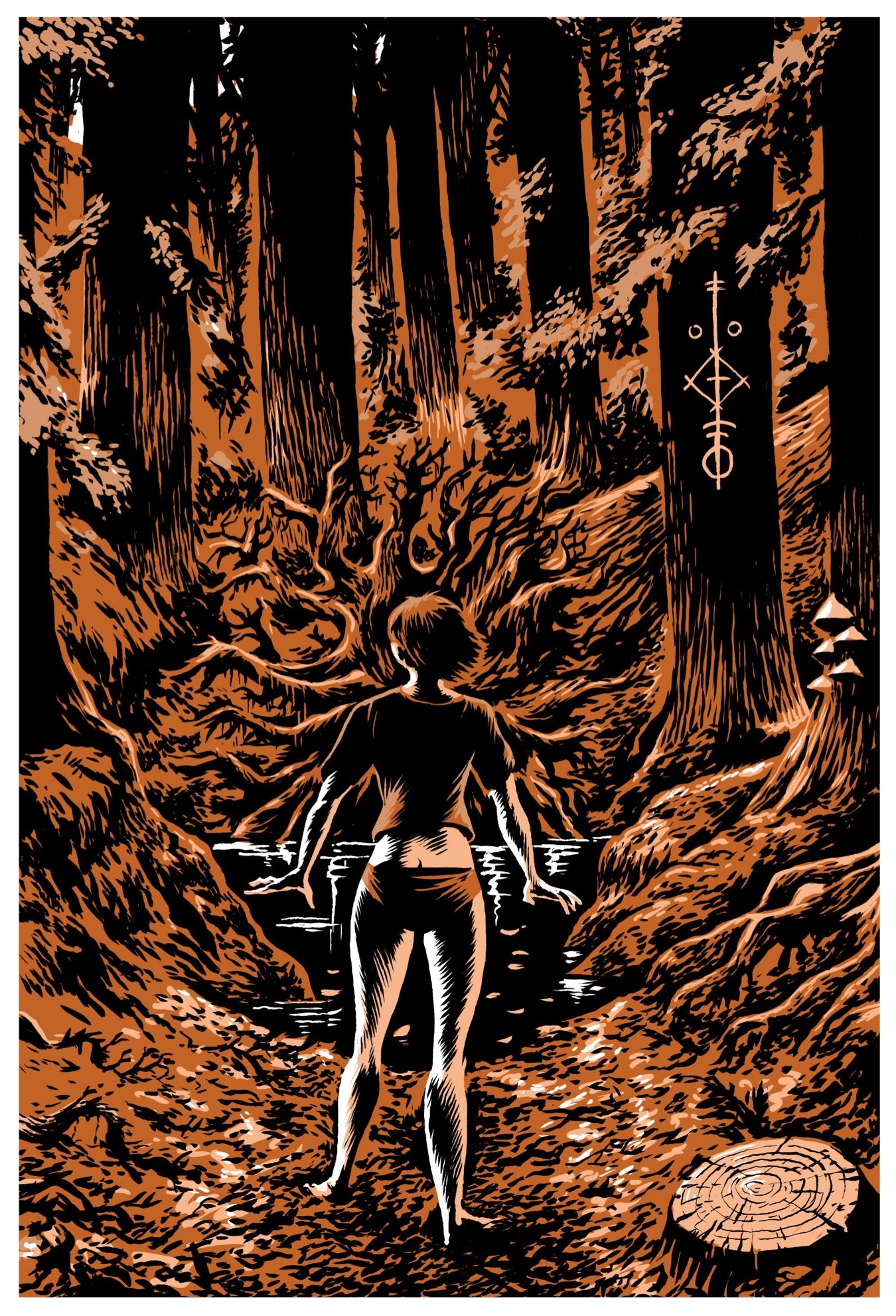

Kriek is a decent enough writer, but he's an exceptional artist, and most of the reason this book is a success is in the visuals. It manages to connect thematically to his previous big efforts by dint of a strong through-line of guilt, bad decisions, and regret among its protagonists, but the rural fatalism of In the Pines and the grand gothic sweep of The Exile gives way to a more claustrophobic throwback of domestic terror and the intrusion of spiritual danger through the medium of the family. But where it truly shines is in Kriek's steady hand and gradual refinement of his technique, and The Pit features some of his best art to date.

His work has always benefitted from the judicious and careful use of color, and The Pit is no exception: Most of the book, from its gorgeously evocative cover to its final pages, is all dark pools of green and gold and impenetrable swaths of blackness. Happy memories — even the ones that turn out to be not so happy — are bathed in a nostalgic orange twilight, aside from the cold grayish blue of Sara's recollections of her son's death. Scenes where the couple are not present are drained and filtered and washed away, as if their absence saps the scene of its vitality, and the subtle gradations of hue and shadow help set the suggestions of dread that build throughout the book.

His inks rival and often surpass the colors to make for an experience that is always satisfying, in spite of a few rocky storytelling moments. From close-ups to nicely framed two-shots, Kriek's characters, even when they're a bit thin, have never been so expressive, emotional, and present. Because of the "something bad is in the forest" component of The Pit, it's important that the natural surroundings in the story do a lot of heavy lifting, and Kriek is again more than up to the task; simple panels of Sara jogging down the empty roads to clear her head are gorgeously composed, and something as simple as the lower roots of a downed tree assume the terrible, fearful demeanor of a nightmarish creature.

Lacking the tonality of In the Pines and the scale of The Exile, The Pit — whose stakes seem lower even if they aren't, and the contemporary setting of which robs it a little of its sense of otherness — might seem like a lesser effort. But it's a fine addition to Kriek's body of work, and his determination to whittle away at his creations, infusing them with more and more expertise with every iteration, makes it read less like an individual work that suffers in comparison to others and more like a variation, a late addition to an artist's period that shows progression and evolution, an arrow that might not be sharp but is pointing the reader in the right direction.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·