Brian Nicholson | August 19, 2025

Christophe Blain possesses one of the finest qualities a person can have, and I’m sure many of his fans resent him for it. The only reason why a cartoonist as skilled as Blain would direct his talents towards collaborating with non-comics people, like a chef in his previous book In The Kitchen With Alain Passard, is that he’s curious about the world around him. In his new book, he collaborates with essayist Jean-Marc Jancovici, and I am surely not alone in thinking, come on man, why aren’t you telling made-up stories about lovelorn cowboys? Presented with a book as serious in its subject matter as World Without End, with its subtitle An Illustrated Guide To The Climate Crisis, it is easy to imagine a Comics Journal reader citing a formalist aversion to nonfiction comics to justify a desire for escapist fiction. Why are we getting this book in English, when Blain has a book about a hot chick on a motorcycle still untranslated?

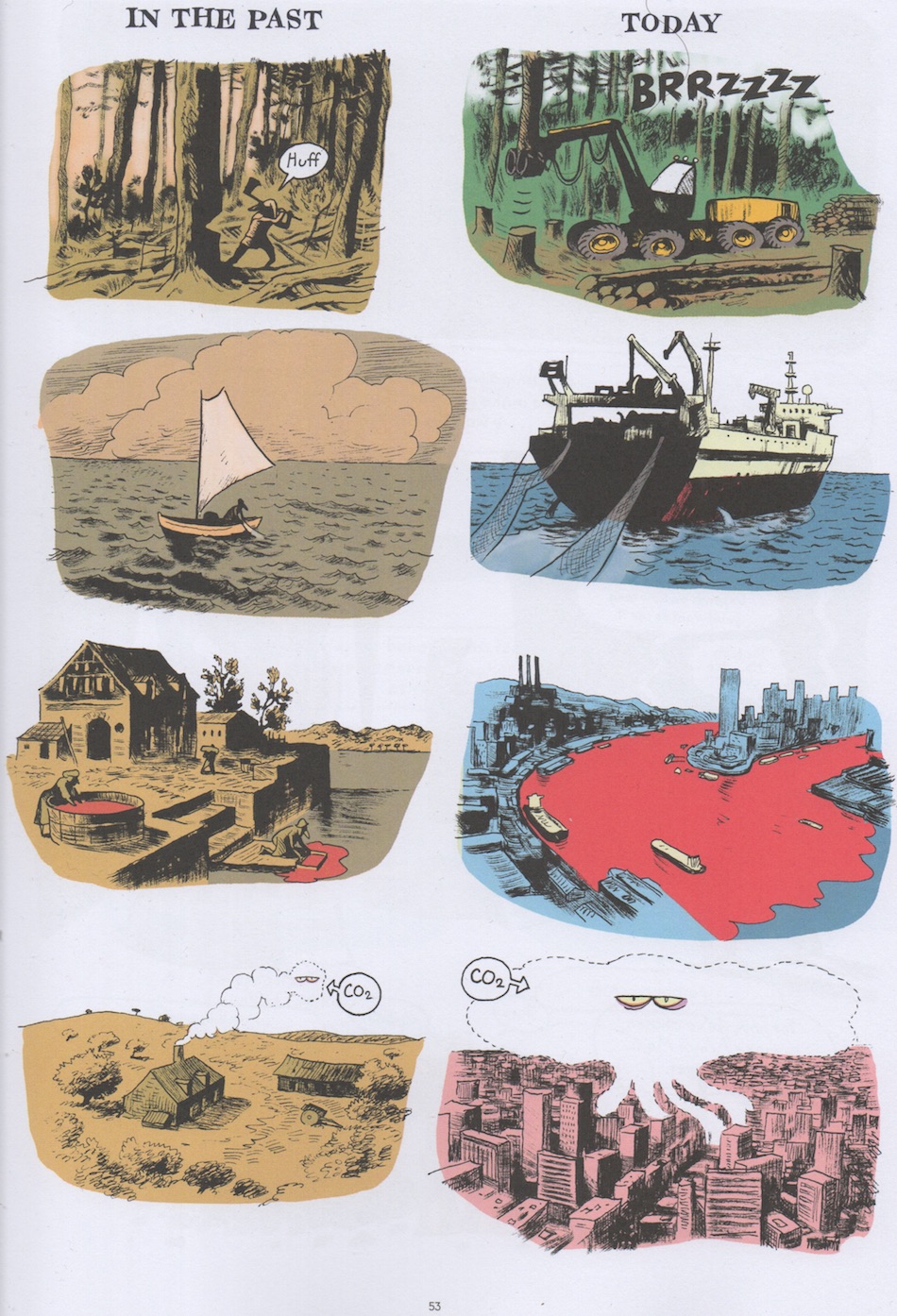

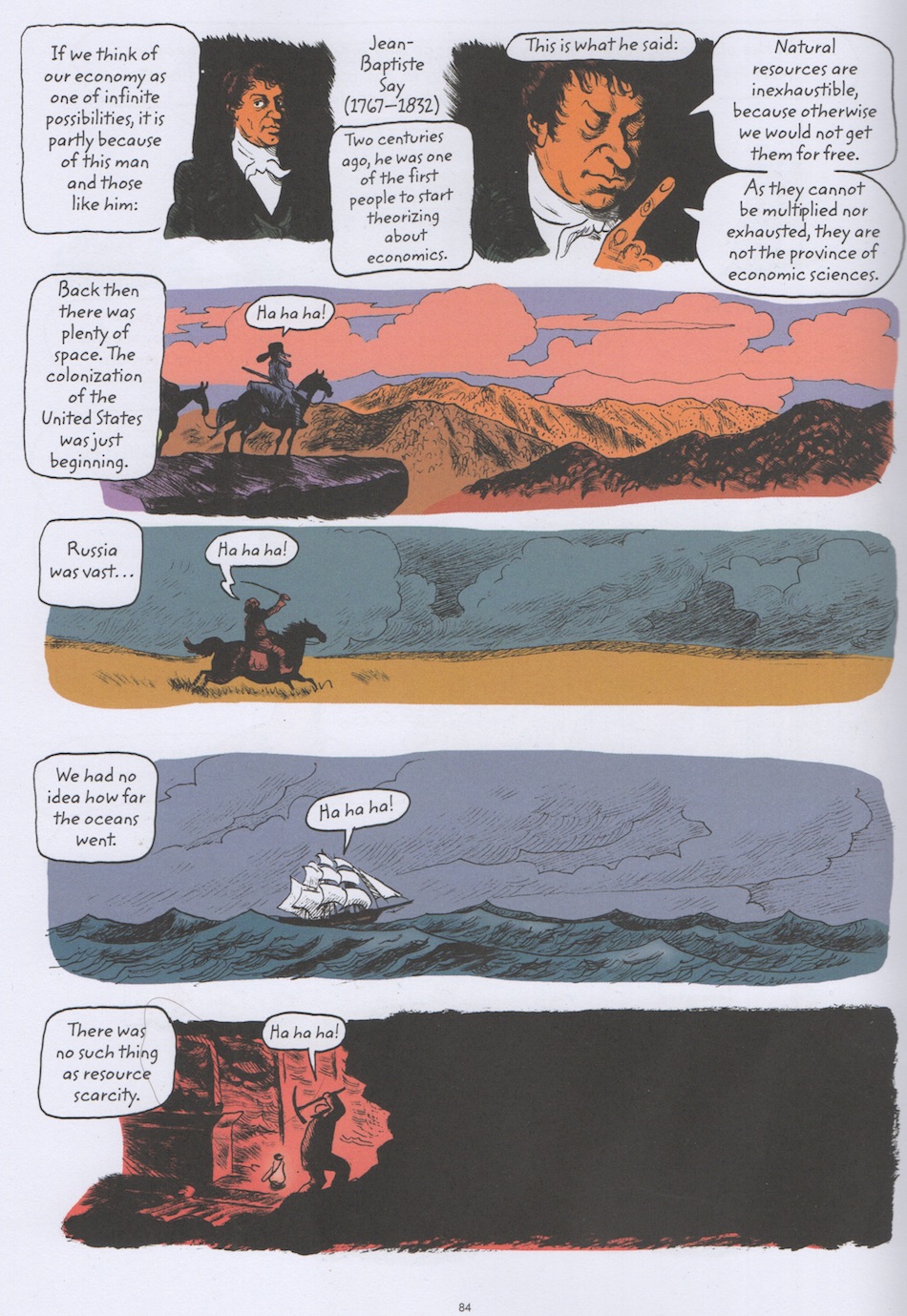

The import is evident, of course, and Jancovici lays out the facts of how we got here plainly enough. Jancovici is not a scientist per se; he’s described as a “science communicator” or “science popularizer.” One thing distinguishing this book from the longform essayistic editorial comics of Darryl Cunningham or the collected works of The Nib is that by collaborating with a writer who is used to making speeches, there is an increased degree of argumentative clarity, a reduced word count that can only come from someone who knows their material and can state it with efficiency. Blain’s smooth cartooning ensures the illustrations of these ideas follow one another with their own persuasive flow. Drawings of cities growing and transforming over time do not inherently owe a debt to Robert Crumb’s "Short History Of America," but Blain can think through the same idea on paper in a way lesser talents cannot.

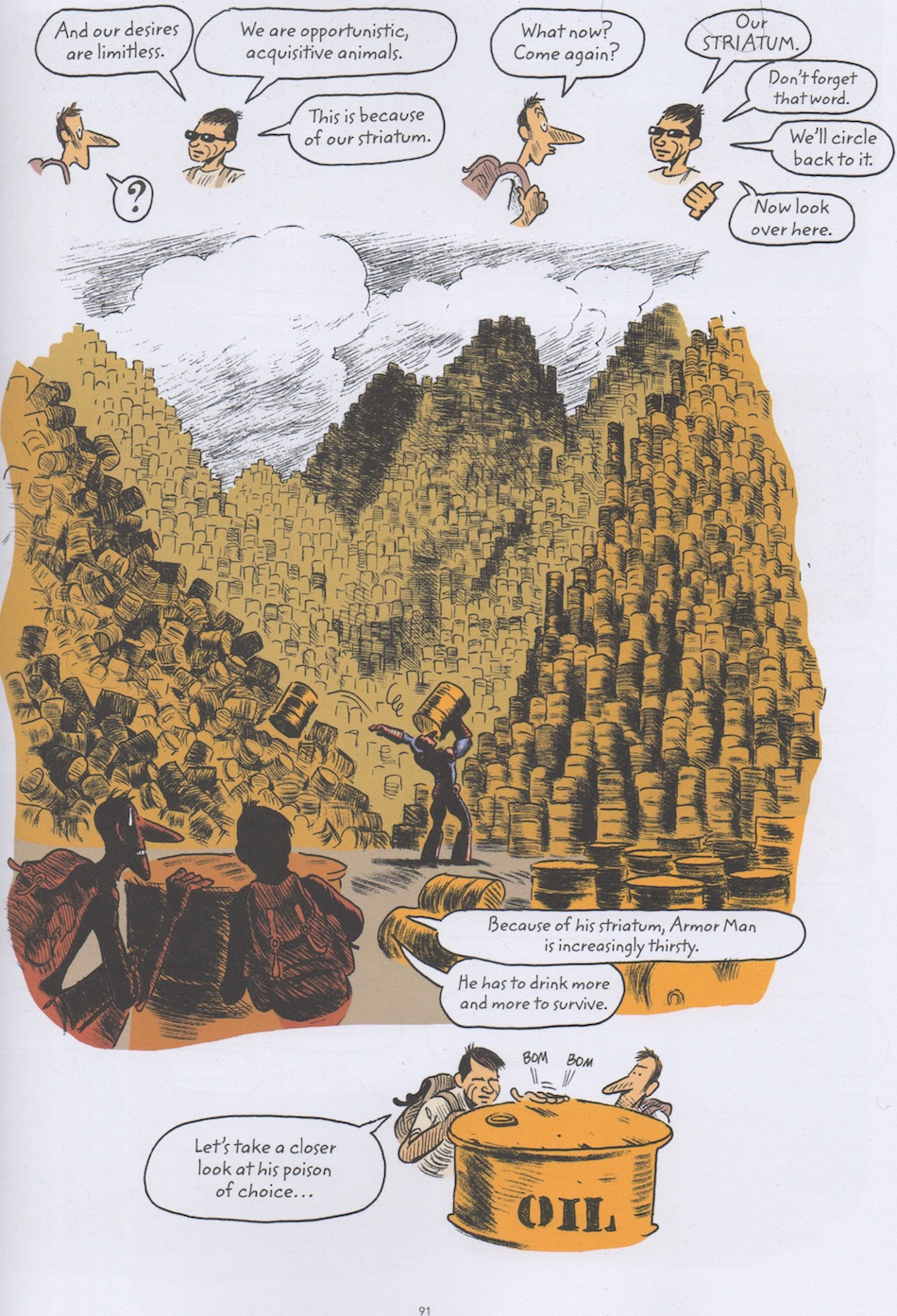

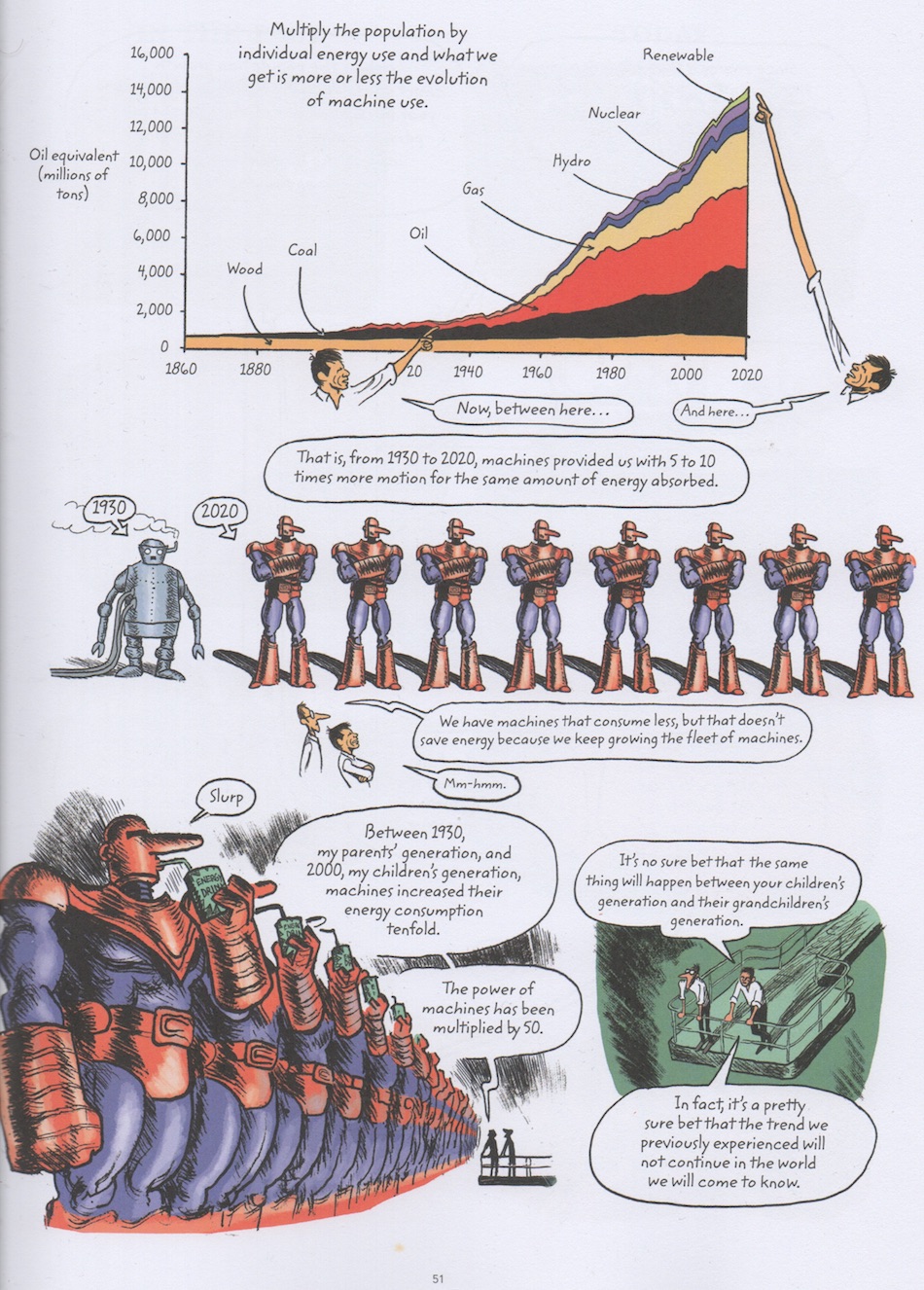

We are given the visual shorthand of “Armor Man,” a superhero who stands in for our reliance on technology to do the things our bodies alone cannot, through expending vast amounts of energy. Our ability to provide food, housing, healthcare and temperature control for an ever-increasing population is attributable to Armor Man. The first half of the book, before we get to discussing greenhouse gases and their role in climate change, is dedicated to reminding us of how much power we use: Not just the computer I’m typing this on, and the lightbulb in my room, but the construction of the house I’m in, the chair I’m sitting in, the mining of the materials so that the city can have wiring and plumbing, the fuel to get the wireless satellite overhead aloft; not just the energy cooking the beans on the stove but the machinery that plowed the fields, transported the food to a store itself constructed by machines running on gasoline. All this to review a book printed and bound on a different continent than both the author of the book and myself the reader, who are in turn located on different continents. All of this creative activity and consumption is often thought of as not taking a lot of energy, because it is not as environmentally destructive as, say, blockbuster film production, a NASCAR rally, the pressing of vinyl records, a highway commute of an hour to work, or a decadent restaurant dinner. It is very easy for a consumer to think of oneself as better than other people and avoid realizing the extent they too are implicated.

This, then, is why Blain draws what could perhaps be conveyed in a Youtube lecture — because the illustration of ideas brings the reader that much closer to actively thinking about something other than the passive act of listening. The information presented demands a response, and presumes an invested audience. That the book was a bestseller in France speaks to both that country’s higher degree of comics literacy and healthier ecosystem for political discussion. Now it appears in America, the country which arguably needs the book more. The U.S. comes up quite a bit as a point of reference, because its energy usage is so much greater than other countries, in no small part due to its greater size creating a more car-dependent culture, and importing a greater amount of its goods from other countries.

Jancovici, speaking to a French audience in 2021, could not anticipate the current moment, with the U.S. ruled completely by grotesque degenerates motivated solely by the death drive. It is to his credit that he doesn’t make partisan appeals. Any world leader worth electing should be invested in averting a rise in global temperatures, as all citizens should want themselves and their children to live in a habitable world. Unfortunately, there’s been a surge in right-wing demagogues coming to power that ignore this pressing problem as part of a larger ideological commitment to making human behavior worse and the enrichment of oligarchs by building ethnostates. Recent developments make it easy to imagine a dismissal rooted in a kind of nihilism of immediacy, where climate change’s salience as an issue of immediate concern is diminished by the presence of state violence on one’s doorstep. The zone is flooded such that you might not be concerned with rising water levels.

I don’t know what to do about the way that we’re wired. I suspect there is only so much space the brain can hold for actionable fears before it brims over into ambient anxiety, dread and despair, but I’m not a scientist, just guided by voices. World Without End concludes on a note of neuroscience, defining “striatum” after alluding to it a few times throughout. Beneath the part of the brain that contains our intelligence, closer to the core of us, is where our want lies, rewarding us with dopamine when we follow our base desires to keep ourselves alive, through eating food or propagating our genes. This, it is suggested, is what got us this far, and it’s not an evil thing to possess the hungers that got us where we are now, even if that place is a precipice. Jancovici believes that, with disciplined sobriety, our world doesn’t have to end. We can no longer view growth of an economy as a measure of success, as that’s a model of economics premised on resources being infinite. We would need to scale back the amount of energy we use, orienting our communities to be more centralized, so that we are not wasting energy transporting resources across great distances. We will also need to get over our fear of nuclear power, as that is the only energy source efficient enough that it can be scaled up to create the amount of energy we need so there isn’t mass death. Much time is then spent addressing the well-publicized objections to nuclear power, which he sees as mostly an issue of optics: The steam emitted from cooling towers may look like plumes of toxic smoke, but it is not. The disaster of Chernobyl would not have occurred were the reactor designed only to generate power and not plutonium for nuclear bombs. Such disasters create fear, which make governments less likely to invest in projects despite any long-term rewards.

More visually appealing renewables, like wind energy, are not efficient enough to rely on, and require such large amounts of space that they are environmentally damaging themselves due to their impact on biodiversity. Blain is often tasked with drawing line graphs, and these delineate the most important facts. No fuel has ever declined in usage; solar panels have not curbed our use of oil. It’s just a heap getting higher, the constant growth we demand of an economy manifesting in increased usage for the most surefire moneymaker there ever was. Jancovici makes no mention of generative AI, whose constant churn of computing power has moved the line upward in the years since the book's French publication. Nor is mention made of the preceding much-hyped waste of computing power, crypto on the blockchain. To maintain a sense of optimism, or speak in terms of our actual needs, one must ignore the existence of these short-term scams best understood in terms of their boiling the oceans.

I certainly would not speak aloud the hope of Pulitzer winner Elizabeth Kolbert, whose front-cover blurb asks, “Can a graphic novel save the planet?” It’s informative even if you still walk away feeling we’re doomed, illuminating even if you still feel our times are at their darkest. There’s value to the act of learning something, or even just being reminded of what you already unconsciously knew. I’m trying to remember if I retained anything about cooking from the Alain Passard book. The fact that I’m cooking beans right now suggests I did not. This is not the fault of Christophe Blain, one of the best of the 1990s vanguard of French cartooning, long elevated to premier status in one of the world’s top cartooning traditions. Here he illustrates what is surely one of the best examples of an informative, essayistic graphic novel you’re likely to see. Hopefully the world will learn something from it.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·