Brian Nicholson | October 1, 2025

Bigfoot, Cartoonist. Photo by Phil O'Connell III.

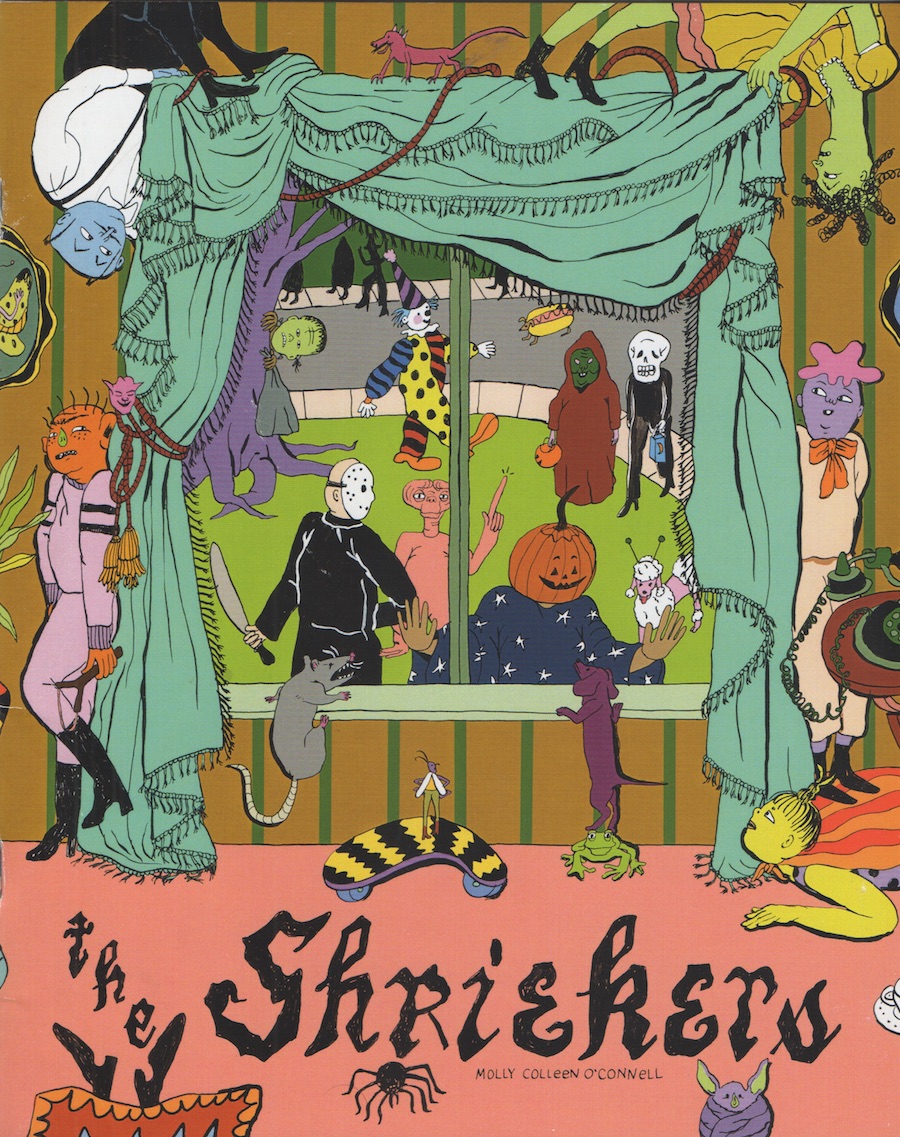

Bigfoot, Cartoonist. Photo by Phil O'Connell III.For the past few years, Molly Colleen O’Connell has been making two of the best comics series. In 2023, she debuted two issues of Pebbles, as well as the initial installment of The Shriekers, and the years since have brought follow-up issues of both. The Shriekers is a Halloween-special-style collection of spooky goofies that's clean enough for kids, but so beautifully drawn the childless adult would not think twice about devouring it themselves. Owing to its family-friendly nature, with issue 2 it was labeled under the pseudonym Mally Wood Lundgren, distancing it from O’Connell’s adult work, which Pebbles announces itself as being by depicting its title character with her tits out and flopping about on each issue’s cover to date. Pebbles is the story of one woman’s life, as relayed through a future technology where, as she is dying, is sent back into her memories to retrieve some bit of information, seemingly related to her interest in ornithology. Much time is spent on Pebbles’ nineties-to-aughts childhood. Both series are visually rich in a way that’s been O’Connell’s longstanding hallmark, yet in their accessibility display a leveling up from the work O’Connell was doing over a decade ago, published with the Closed Caption Comics collective during her days at MICA in the late aughts. Her 2012 solo comic book Difficult Loves, published by Domino Books, was reviewed on TCJ by Sean T. Collins, as was her later zine, Don’t Tell Mom, in 2014.

After a single issue of Stripp Mall, which seemed like the start of a longer work, new comics from O’Connell seemed thin on the ground, at least from my perspective, as they left Baltimore for Chicago to attend graduate school in 2015, studying multidisciplinary art, and making a great deal of non-comics work, much of it documented in the risographed monograph Who’s Afraid Of A Florida Woman, published by Colorama. Chicago is an appropriate home for O’Connell, as so much of the cities’ hand-painted signage and window displays bears the influence of H.C. Westermann and The Hairy Who. O’Connell’s work most recalls the work of Gladys Nilsson, not coincidentally the best of that lot. It is also famously a big comedy city, and O’Connell’s voice and affect recalls for me the comedian Amy Poehler. I have heard, and this is perhaps apocryphal, that Poehler, like Jack Black, is one of the comedians whose success enabled them to buy original comic book art from '90s alternative comics greats. O’Connell strikes me as an artist whose sense of humor and point of view would connect with people who engage with the form through means of high-profile public performance. A few years ago, I suggested she reach out to the people involved in the Chicago comedy night Helltrap Nightmare, led by Sarah Sherman, now a Saturday Night Live cast member specializing in plying body horror for laughs. O’Connell, who just last year made a Halloween costume of Aylmer from Frank Henenlotter’s Brain Damage, would seem like a kindred spirit.

In a bit of audio lost to my phone unexpectedly restarting, O’Connell spoke excitedly about traveling to Mardi Gras, describing it as being like Halloween on steroids, and how it felt like the the way humans were meant to live, parading in the streets and playing drums. A costume of the moon made for the event led to a performance at a comics reading wherein the Moon talked about the comic it had made. This comic is not in print, but rather a live performance exclusive. There are plans, alluded to on the cover of Shriekers 2, to return to the world of Stripp Mall, and in the another chunk of audio lost from the transcript, it was revealed this might be done under yet another pseudonym, just for fun. That was ten minutes lost after talking for two hours, but O’Connell has such an omnidirectional practice that there is much we didn’t get around to talking about. We didn’t talk about her hand-painted t-shirts, bits of wearable original art that are another way O’Connell contributes to the visual culture of the larger world. This is most in evidence in Chicago, where a few years ago O’Connell painted a mural to the wall of a social club in exchange for being able to host her wedding there. More recently O'Connell designed the poster for Pretty Good Fest, a comics expo taking place on Oct. 4. O’Connell will not be in attendance, but their books will be available, sold by her husband Chris Day, who will be debuting his own book published by Perfectly Acceptable Press, XO, while O’Connell will be tabling at Philadelphia’s Philly Comics Expo. Owing to their ability to occupy multiple places at once, this interview had to be edited significantly for linearity and legibility to those not occupying quantum states.

BRIAN NICHOLSON: When did you start meditating?

MOLLY COLLEEN O’CONNELL: I’ve been attempting to have a meditation practice for over a decade. But taking it seriously and doing it every single day started in February. Doing it multiple days a week but not super-strict, maybe like two, three years or something.

What do you get out of it?

I really need that time. My brain wants to be firing. I feel like normally with teaching and just being present, I’m always spinning a couple tables at once. That’s my instinct. I think I had a hard time sitting in silence. With meditation I have to sit down. You’re just letting the steam out of your brain, like a little vent. I think it’s really good as a visual person too, because we’re all taking in so much visually all day and so to close your eyes and let your brain reset is very very helpful.

Would you identify with Buddhism or any kind of larger spiritual framework for meditating, or is it more just something you need to do physically?

I wouldn’t affiliate myself with any one thing. I went to Catholic school for two years and it really fueled a cynicism and a skepticism of religion for a long time, but I think now I have a real appreciation for however people find structure and community. It makes sense in a different way why people go that path. For me it’s more for my body, my brain. But I think it helps me be a better community member.

When did you go to Catholic school?

I went for Pre-Kindergarten and Kindergarten, but I have siblings who went to Catholic school all the way, like pre-K to graduation from high school. But my family couldn’t afford Catholic school anymore and I think my dad was finding himself at odds with the theology too. They just put me, and my siblings right above me, into public school. I was at an age where I was just playing games with nuns, I was kind of in the cool part of catholic school, but for my older siblings it was much more traumatizing. And my dad was brought up super-strict Catholic. I mean, I’m an O’Connell, you know? I felt a real freedom, but I inherited a lot of their issues. I was the youngest of seven. I was taking in a little bit of everyone’s interests. When I was teeny-tiny, and all of my siblings were there, I had a goth sister, and a brother super-into Frank Zappa, and I had a preppy sister who was into super-explicit Miami booty bass. The first things that were really inspiring to me were musicals.

What do you mean by musicals? We talking movie musicals or original Broadway cast recordings?

Some Andrew Lloyd Webber, some real eighties, Les Mis, Cats, Jesus Christ Superstar. It wasn’t the music necessarily. It was the PBS specials, you could watch the tapes. Or seeing traveling productions. It was just cool to see people making something in the moment, and costumes and makeup and sets. It seemed more “I get how this was done,” than how movies were made. They were just really exciting. I saw a production of Cats where they crawled through the audience. A classic.

Hand-painted Cats t-shirt from 2020

Hand-painted Cats t-shirt from 2020

I also heard on your Thick Lines interview that you were more of a kids book person than a comics person. What are some good kids books? What should people be looking for?

I love an old newsprint book with simple spot color. I got a huge haul not long ago from a church sale, one woman’s collection from the sixties, seventies. Comics were one of the main things that didn’t feel super-accessible when I was young. Going to comic stores and CD stores as a young femme-presenting person, it never felt very comfortable. I loved Betsy-Tacy, you know that series?

I don’t know any kids books, I didn’t read them that much. I would be reading chapter books that didn’t have that heavy visual element.

It wasn’t really to read, it was to look at the drawings. It was my version of spending a lot of time looking at art and drawings. What’s that couple that did the Greek myths books? [D’aulaires Book Of Greek Myths by Ingri and Edgar Parin d’Aulaire] Maybe it had something to do with a lot of the artists were women too. It was just more exciting. I just liked the way they were drawn. Everything was really soft. [Molly holds up Caps For Sale by Esphyr Slobodkina, as well as Maurice Sendak’s In The Night Kitchen.] I was at Max Morris’ house last night and he had this Richard Scarry box set I was really jealous of. [Holds up a book called Peter Churchmouse by Margot Austin.] She’s one of the ones I’m talking about that does really soft, pencil or litho crayon texture. They’re beautiful. There’s something really satisfying about the seriality of kid’s books, you can reread them a bunch of times. I also nannied quite a bit, so I was reading kids books a lot longer than someone would, even aloud. You have to get the kid to enjoy it, so you have to get into it, you have to make it come alive a little bit. Petunia, Beware! by Roger Duvoisin. Look at these insane color separations. The printing was exciting. The drawings were exciting. I kept collecting children’s books for a long time just because of looking at them as artworks. When I started making work that would I guess be called comics I didn’t even know what to call it. I called it children’s books for adults. I was so much more influenced by that work and that look. This was in in high school. I realized they’re just comic books.

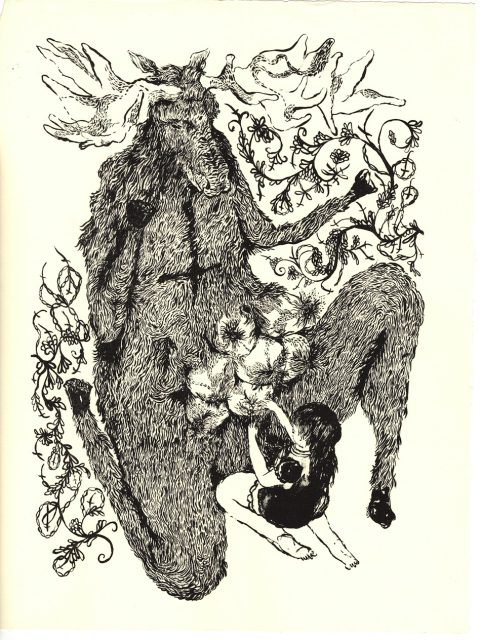

Moose Mother lithograph, 2007

Moose Mother lithograph, 2007I have this Windy Corner Magazine, you’re in issue 3, (drawing the table of contents, which is dated as “drawn from summer 2008 to winter 2009”) but also all of them have Austin English talking about children’s book illustrators. This one is talking about Garth Williams. [Issue two has an article about Lois Lenski, the artist of the first four Betsy-Tacy books O’Connell mentioned, although the illustrations in the later books are by Vera Neville.] Your bio in the back, [dated summer 2009, and seemingly written by Austin] starts with “Molly Colleen O’Connell is the artist behind many of the best minicomics from the last two years: BBB’s Diary Summer and Peechiesa Fall.” I don’t think I ever saw those.

I didn’t print that many of them.

When I met you and would talk to you about your comics, at shows where you were selling them, everything was an artifact from a fictional world and there wasn’t anything that was a straightforward comics narrative. You had this whole mythos in your head that maybe you were one day going to do as a comic, but maybe it was always going to be only this thing. What do you think about that stuff now?

I still like some of the concepts, it’s hard to like the drawings from this distance. But that work, I think at the time I just had a hard time accepting and liking my writing. So I tried to work on it through visuals. I really liked the planning. But I didn’t understand where to put my labor in comics yet, and I think it’s because I was reading a lot of that material for the first time. I was learning comics from Brian Ralph, who was a Fort Thunder alum, though he was of the more traditional cartoonists [from that group]. I wasn’t quite resonating with that work yet, I was interested in the really dense visual stuff.

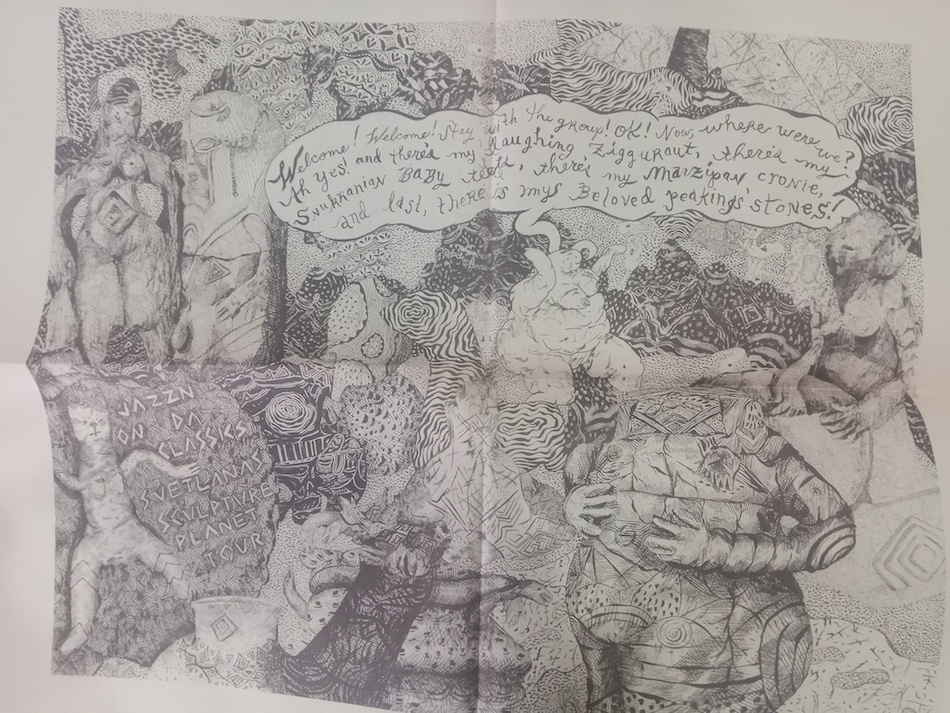

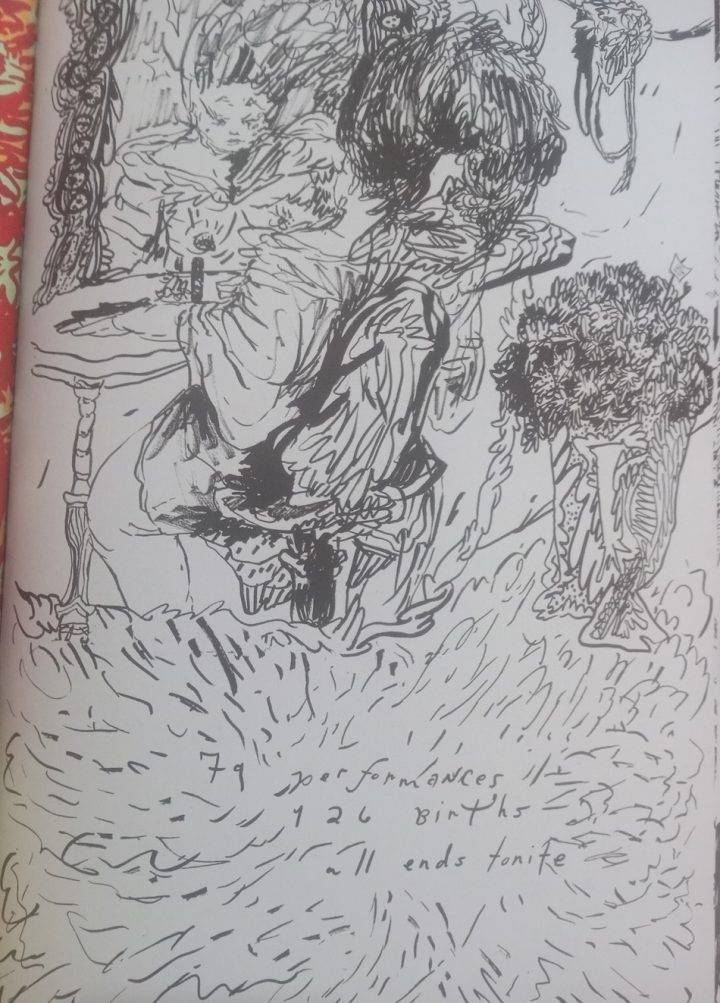

Greatly reduced spread from the oversized newspaper Vajazzlin, circa 2011

Greatly reduced spread from the oversized newspaper Vajazzlin, circa 2011When you were getting into comics, what was the stuff that started to connect with you?

I loved Ron Rege’s work, because I liked the sensibilities of how the text and image merged or blurred. Everything felt animated and alive. They’re just beautiful doodles. The stories felt more of the present time. It was easier to ease into reading that stuff. I think there is something about being introduced to comics at a young age, where it's exciting if you understand how the marks are being made. The intensive rigidity of some classic comics work is a little bit alienating. I don’t know how they made this. But the Kramers that has Shary Boyle’s work was super-inspiring

That’s in Kramers Ergot 6.

I would fall asleep holding that sometimes. I wasn’t thinking of being a cartoonist yet, but I wanted to make kids books that were more risque and not for kids, that were a bit transgressive or subversive. But I also think I was nervous to write that stuff, but I didn’t mind drawing it at all. Like Lost Girls, that Melinda Gebbie book with [Alan] Moore, was a tome that just made sense.

That also came out right in that era.

Yeah, I started going to SPX. Picturebox, Buenaventura, that’s where I would spend most of my time and money. But also meeting a lot of folks, I always felt like I didn't quite fit in because I still didn’t know if I was even making comics. I was making this weird print work that I wanted to build to comics but I was still figuring it out. Comics was so laborious. I couldn’t get into that labor. I was in a place where I was so excited to be making stuff, I would change gears a lot. I was living in Baltimore and everyone was doing everything. Everyone was in a play, but also writing music, but also a DJ but also … It was really inspiring. At MICA I was like that too. I wasn’t making comics all the time. I was making costumes and masks.

Image from Vajazzlin, circa 2011

Image from Vajazzlin, circa 2011With the comics, I can think of who were your peers, like the Closed Caption Comics people, but with the multidisciplinary stuff, like dressing up in a costume, I don’t know if you ever felt like you found a community there that was doing similar things or supporting you in the same way.

performing Don't Tell Mom at Carousel

performing Don't Tell Mom at CarouselYeah!

Like who?

At the time, I was performing at weird bars in Baltimore like The Crown or small venues. There was definitely a weird comedy scene. Some people were going for more straightforward stuff, but there was a lot of space for weirder stuff. One of the first times I performed I was in a “poetry reading by Virgos only” organized by Bela Sheyavich. Or comedy nights hosted by Lexie Mountain or Ben O’Brien. Performing gave me confidence in my writing, honestly. With most disciplines or things I’ve been interested in, I always have to trick myself into doing it. I tend to take this way more complicated back route, I don’t know why. It’s the same thing with comics: I could’ve just tried telling the story I was telling people this thing was about, but instead I had to say, this is a prayerbook that exists in a world. It’s fine, it probably would’ve been really bad. I think my instinct to just make the thing that was most exciting to me in the moment was a good instinct. I was trying to figure out what I wanted my work to look like.

It makes sense, because the tradition of a lot of cartoonists was an extension of vaudeville. I think a lot of them would rather be performers, and not just sit all day drawing. You have to find things to write about, and if you’re spending all your time solitary, that can be hard. But now I love it. I feel a lot more confident in my ability to tell a story but a lot of the writing experience that I accrued was through writing poetry or monologues or jokes.

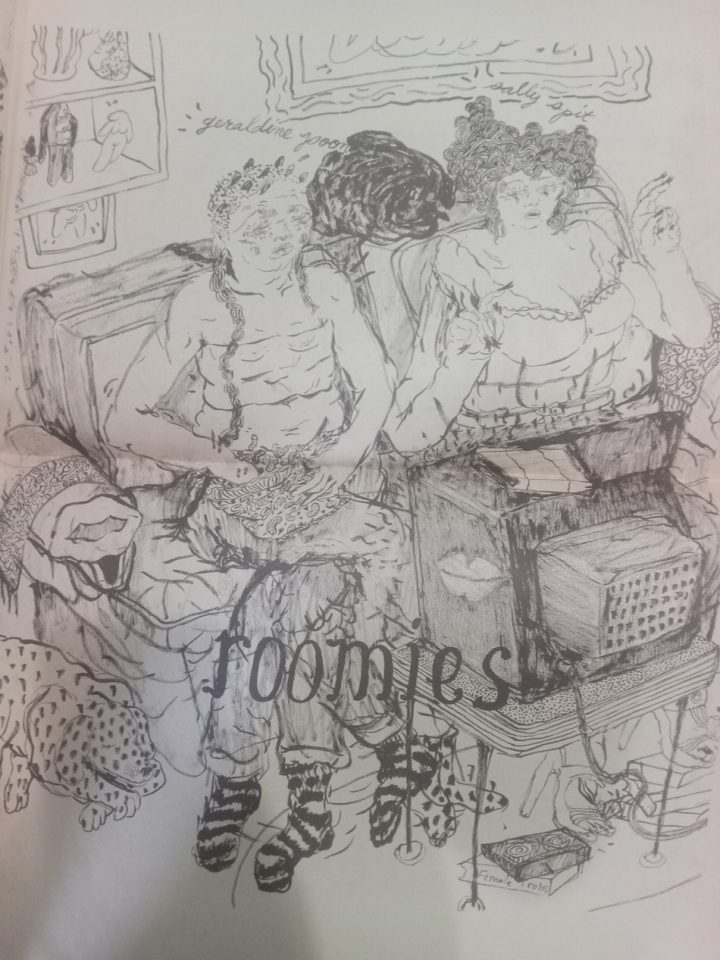

Cover to issue 1 of The Shriekers, 2023

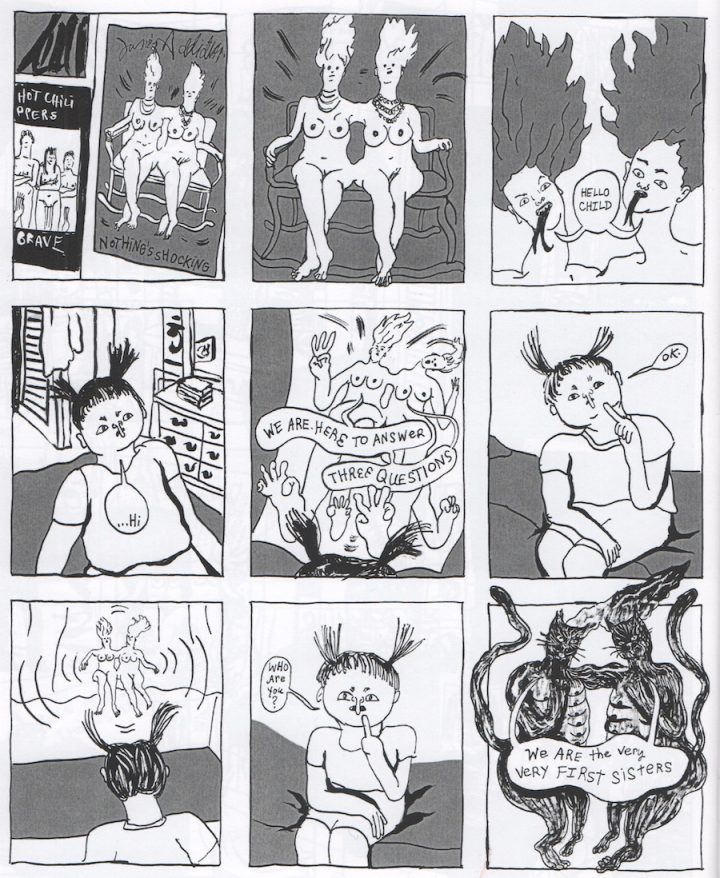

Cover to issue 1 of The Shriekers, 2023The Shriekers is a pretty funny gag comic but I feel like all of the gags are visual. It’s really built around visual ideas more than characters. Do you feel that way or do you feel like you totally know what the deal is with all the characters in The Shriekers?

I think I know more than the reader, but I find a lot of it through drawing them. I guess that’s why Shriekers and Pebbles are two different writing approaches, because Shriekers is a lot more visual and writing through images and thinking about movement, but I do have concepts about who those characters are.

Do you want to expound on some of the lore that a reader might not be aware of?

[Later, in a chunk of talk that got lost when my phone reset, Molly talked about the cover of The Shriekers 1 - the idea that these spooky characters might hide from the world when the rest of the world is spooky for a day, dressing up on Halloween. But now she feels as if they would love it.]

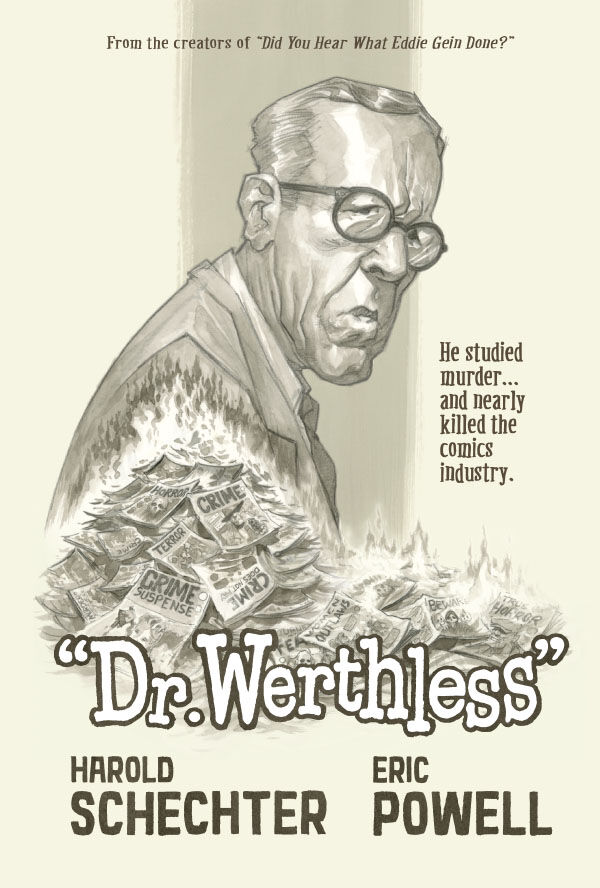

Something that’s important to me is they all live together but aren’t necessarily traditionally related. It’s more of a found situation. I wanted to make a horror comic for kids. I think that’s underserved, or I think there are a lot of horror things for kids, but they look awful. I don’t like how they look. I just wanted to try making something, it’s not explicit, it’s more gross. So with the characters they each serve as a different avenue for joke-making. Like the Marge character is a traditional elder witch. They all look kinda like kids, but they’re all kinda ageless too. They’re spirits or ghouls. Shigeru Mizuki is a huge influence on this. GeGeGe no Kitaro is able to be silly but I think kids have a curiosity about death and violence and I think drawings are a way to think about those things but not in a traumatizing way. Mizuki was also really inspired by EC, and I think a lot of people inspired by EC felt robbed of the trajectory of that work.

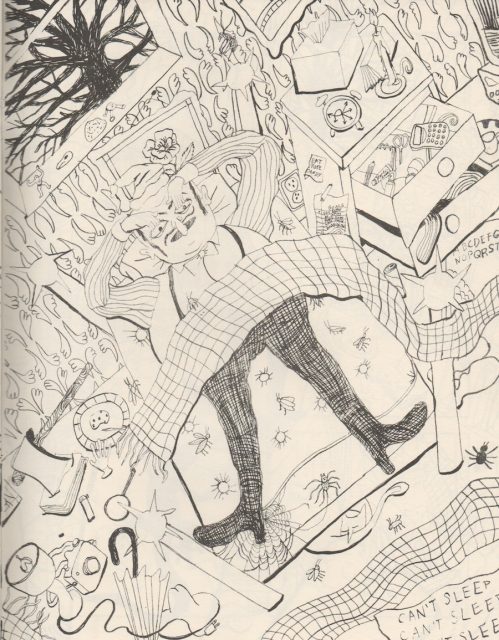

Page from the conclusion of The Shriekers issue 1

Page from the conclusion of The Shriekers issue 1At the end of Shriekers 1, Regimold is laying in bed with his eyes open and it’s going further and further out around the room, what is your writing process for something like that?

Because it literally happened. I was laying in bed and unconscious of being like this [pulls her eyelids back with her hands]. I said aloud, I’m so tired, why can’t I fall asleep? And then I realized I literally was like this. This is inspired just by insomnia anxiety and the joke of how much of this is self-imposed. His room is insane.

Is your own bedroom as visually cacophonous?

No. Especially at that time. This was a while ago. I drew a version of Shriekers [before the version now in print]. The first ever image of Shriekers is the poster I did for Colorama.

I don’t think I’ve seen that.

In Clubhouse 10, which is really hard to stay bound because it’s duct-taped plastic sheets. Do you know the Clubhouse project?

I do, but I would like to hear you talk about it and your experience with it.

Johanna Maierski and Aisha Franz would invite artists, through connections they made internationally or through the internet, to make a single poster image that they would then send to another group of artists they would invite to come to Berlin for a week to make a comic in response to the poster they were paired with.

Did you get to do the residency?

This year, [the year of Clubhouse 10] no. I met Aisha a while ago, in 2014 through Nick Houde, and we just hit it off super-well. She had come to Baltimore to visit and stayed at Floristree. [A now-defunct warehouse space in Baltimore where many artists and musicians lived, including O’Connell and Noel Freibert, and many many shows were played.] It was really exciting to meet someone who was also inspired by Kramers and a lot of the same material, but also living in Berlin and growing up with a much more European understanding of comics, but also at the same time is from Colombia and seeing comics from there. She was such a master at such a young age. She had her chops. She made Earthling as I think her senior project in undergrad, which is insane, because it’s such a beautiful and complete book. And then Johanna came to Chicago years later and was tabling next to me at the Chicago Art Book Fair that Conor Stechschulte had helped organize. We just happened to be sitting next to each other and immediately became best friends, just fell in love. There’s people you connect with immediately on a humor level and also just seeing the incredible work they are making. I’ve had so many of those kismet people where you meet and just immediately know. And so they invited me to do a poster. That was a way to stay in touch with an artist they had just met, but also they have these friendships and connections they were fostering at the same time. So if you did a poster one year, the next year, they might invite you back for a full residency, so I did the full residency in 2019.

Who was there with you?

[Digs out her copy of Clubhouse 13, with a cover by Aisha Franz] I don’t want to forget anybody. Stefanie Leinhos, Johanna’s partner. Bridget Meyne, a British cartoonist. Jooyoung Kim, from Seoul. Melek Zertal who I think was based in the Bay at the time but is maybe now in France, he moves around quite a bit. There was Lasse [Wandschneider] from Berlin, Lale [Westvind] was there, Michel Esselbrügge, Antoine Eckhart, Stella Murphy, Juliåna Chomovå. Noel [Freibert was in it [contributing a poster] but not there. And Maria Medem. I was paired with Haejin Park, was the poster I got. Have you seen this comic?

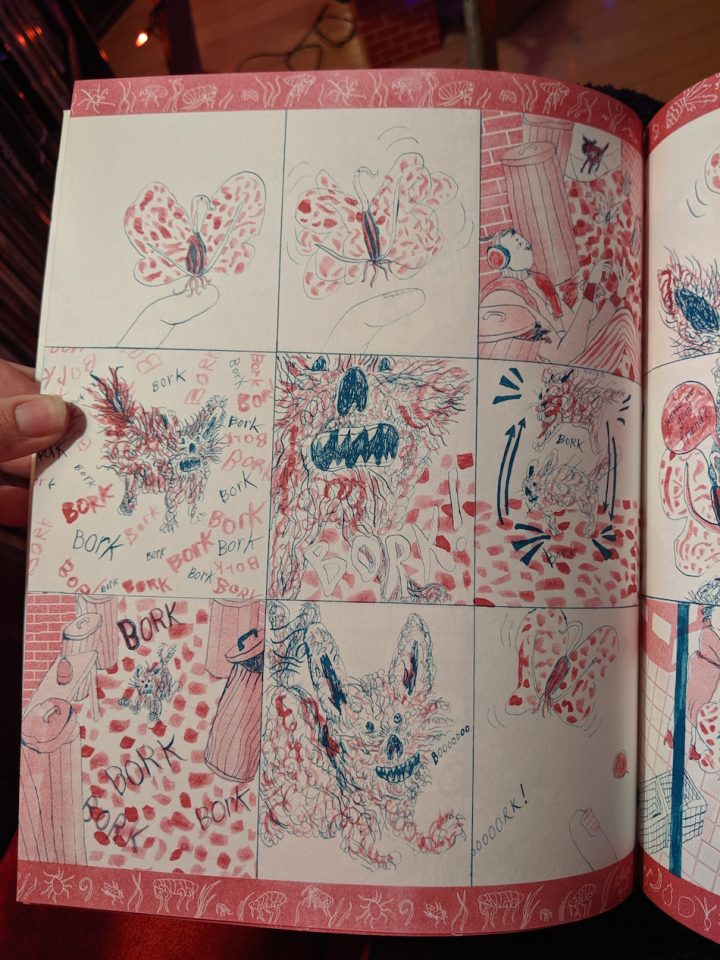

O'Connell's comic from Colorama Clubhouse 13, 2019

O'Connell's comic from Colorama Clubhouse 13, 2019I don’t think so.

They would also do different versions of the residency. Between this one [10] and the one I did [13], they had done some shorter ones that were just with more local artists, or I know they did one in New York.

Was there anybody you met for the first time and really hit it off with?

Yeah. The way it was constructed, the first night you have this huge picnic at this place that used to be an airport in Berlin. It’s just a very beautiful time of year. It’s early to mid-Summer. Lale was someone I’d already met and been close with, but it was really exciting to meet everybody. It was really affirming. I think I still had a little imposter syndrome because I had a hard time identifying as a cartoonist. Even at this, Johanna scared me so much with “you have to finish in five days to print,” and at this time drawing was so labor-intensive, and I don’t love drawing with other people. Cartooning I really like to do very solitary. It’s just a comfort thing. I can doodle with other people but it’s hard to make comic work. This was a real transition period when I was starting to make more comics work again, and I was nervous to do that in front of people. This was before Shriekers or Pebbles being drawn. I loved everybody. I wish I had been there longer, I had to leave early, before the book was released, I think because of teaching or something stupid.

Can we talk about teaching? How did you go from being in grad school with a multidisciplinary major to teaching comics history?

I started teaching a bunch of stuff. Painting, printmaking, drawing, history of comics, advanced studio courses. Lots of ages, younger folks, older folks. For the university’s undergrad I’ve taught predominantly comics history and comics studio classes. Right now I’m just starting to do a fibers comics class.

What does that entail?

I just had the first day yesterday. It’s gonna be experimenting with different physical techniques, but using narrative or comics as a structure or way of reading. It’s gonna be narrative-based but physical. So they’re learning screen printing on fabric but also embroidery. It’s a lot more open-ended, but it basically means cartoonists who have access to tools and materials in a studio context.

Silkscreened page from Preguntas, a very large format publication, circa 2011

Silkscreened page from Preguntas, a very large format publication, circa 2011How have you found your way into comics history? What is the work that your students respond to that doesn’t mean as much to you?

Jessica Campbell helped me get this comics history teaching gig. I sort of knew headline comics history, but not very in-depth. There was a lot I didn’t know. That’s the magic of teaching, in a way you’re also the nerdiest student in class, so you get to put all your focus in that area and your job becomes reading a bunch of material that I otherwise wouldn’t have time to do in such a condensed time period. I mostly taught what I was psyched about. We would start with reading Obadiah Oldbuck by Rodolphe Töpffer, and look at some print history, like Goya and [William] Hogarth. I like to begin with a framework that has a generous definition of comics, to shine light on how much art history can be in conversation with the medium. I got way more deeply into underground comics of course, but also the super-absurdist or surreal early Chicago Tribune artists like [Lyonel] Feininger. The most impactful work for me that sparked, “Oh fuck, I do want to make comics again” was a lot of French comics from the seventies like Chantal Montellier and Nicole Claveloux. It was important for me to share a lot more queer and femme representation that I just didn’t know or hadn’t read. Just stuff that was a lot more challenging to read. Because I think I was trying to do that with earlier comics work, make work that was not very direct or sequential, but was more giving you a narrative through multi-sensories, but I don’t think I was very good at it. I was just attempting to do it, but finding work that was very successful at that, that wasn’t just crime-based or sci-fi. I guess some of that stuff’s sci-fi, but. I mean, Claveloux went on to be a children’s book illustrator.

With Pebbles, you were saying that was a different part of your brain or writing process than Shriekers. Let’s try to figure out the basic timeline. She’s a child being neglected by her mother in the early '90s, and then she’s a teenager in the early 2000s. How long of a life does she have, because it goes into the future. Do you have a sense of when her sci-fi timeline deviates from ours?

I feel like that’s too simple or something. It’s already its own construction, right? There’s something of our world but also not. It would be too easy or too dumb to say it’s like me, because it’s not. But of course there’s parts you pull from yourself for characters, or your references or nostalgia for these visuals you’ve spent so much time with.

What is it about the nineties that’s so compelling to you as a setting?

I feel like it’s something I can just easily access. I was a little kid when all these teens of the nineties had their teen nineties bedroom and I could pop in and marvel at the taboo, because it all felt, for the age I was experiencing it, really intense. Because it was the nineties, music was just trying to have some resurgence of weird, sex love rock and roll. Some of it’s pretty corporate, but there’s humor to those images too.

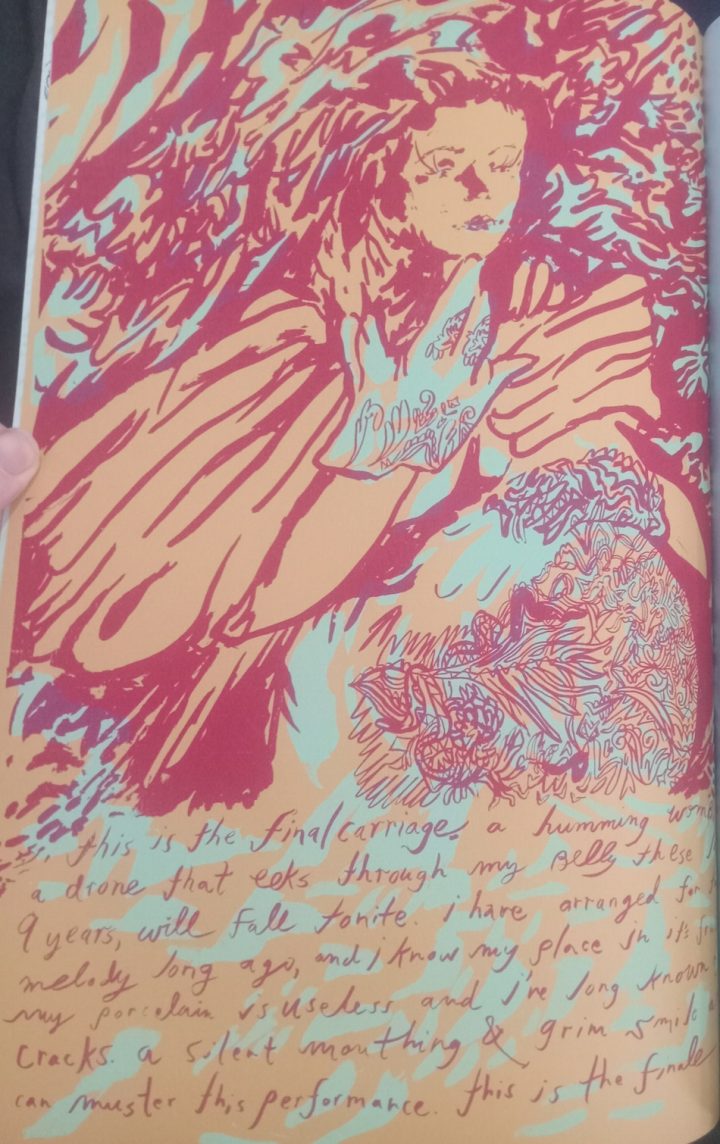

Page from Pebbles 3, published 2024

Page from Pebbles 3, published 2024The Red Hot Chili Peppers with socks on their dicks.

Yeah, it’s corny, but you know, it worked. It’s like the audience for it is the little siblings, or the people who will be pissed off or shocked by it aren’t the people actually consuming it. It’s fun, and I like working in a period piece where the research is just, some of those bedrooms are based on my sister’s bedroom. And I like that half the book has tech that the other half can’t conceive of yet.

With Shriekers, in Conor’s blurb, he describes it as Garbage Pail Kids meets Addams Family. Were you into Garbage Pail Kids as a youth?

Yeah. I still have a decent amount of the cards. They’re wrapped in a rubber band, they’re horribly archived, but I love them.

There’s the Marc Maron question, “Who are your guys?” question I wanted to ask — who are your guys, specifically from the Garbage Pail Kids?

[O'Connell points their camera to framed art on the wall]

Those are Wacky Packs.

I know but these are the only ones I have specifically framed.

You have Evil Time, and Cover Ghoul, and Scared Decomposition Notebook Wacky Packs.

I got Mitch Stitched on my water bottle. [Sticker is affixed.] There’s a real nasty snot girl, Leaky Lindsay. Those were the things, [from] my brothers having collections of stuff, I was allowed to have. I think it’s just because they were like, “Oh she can’t break these,” but comics they were nervous I would muddle their collections.

Also with The Addams Family, what are you thinking of? Are you thinking Christina Ricci and Anjelica Huston or are you thinking Charles Addams New Yorker gags?

This was something Conor said. I love those movies, but I think what he’s referring to is the Charles Addams shorts, which I do love. We have this one book that Chris [Day] traded some art-handling labor to get. It's a book of photographs of things fans had mailed him. It’s called Dear Dead Days. It catalogs things like weird apparatuses for attempted murder by execution, photos and postcards of freaky images that they thought would inspire him for more material. I love this, just thinking of him getting these. It’s also a beautiful book. I love that relationship. Have you ever mailed anything to an artist or author you really liked?

I don’t think so. I should. Have you?

Yeah. I mailed zines to Amy Sedaris once, I never heard anything back.

Zines that you made specifically.

Yeah. I’ve had my share of pen pals, but I’m trying to think of people I cold-lettered. I remember when I was little I entered a mail-in contest to win lunch with any celebrity. I wanted to meet Tina Turner and wrote an essay about why I wanted to have lunch with her. I would love to read it now, but it was handwritten, so I have no idea what it said. I just remember it being about Tina Turner.

You mentioning Amy Sedaris brought up this other thing I wanted to talk to you about, our shared late-nineties Comedy Central fandom and comedic influences. Amy Sedaris is a good example of a person I can imagine you thinking, “This person would like this thing that I made.” Maria Bamford came into Partners And Son and after she left I realized I should have just given her a copy of Shriekers, you would’ve paid me for it. That was a real fuck-up on my part.

Gina [Dawson] was wearing a "Feral MILF" shirt when Maria Bamford was doing a signing there, and sent me a picture of her in the shirt. Someone has also met Carrot Top while wearing that shirt and sent me a picture of them with Carrot Top. And both times, the person did say “love that shirt.” So Carrot Top and Maria Bamford do approve of something I made I guess.

You love a person doing a character.

Yeah. Amy Sedaris is a huge one. Just the other day we were talking about Upright Citizens Brigade — the show, not the school — was huge for me. Also Mr. Show and Dr. Katz.

And of course, we can’t forget Strip Mall, the show only you remember, and I never saw.

No, you can watch it on YouTube now. Did I not send you clips? There’s a whole episode on Youtube. It’s not a great show.

Can we talk about how it inspired your series Stripp Mall?

The connection is I loved Strangers With Candy, and at the end of the third season they are blowing up the school, because they’re turning that lot into a strip mall which becomes that show, because they were being canceled as Strip Mall was being made, and they randomly connected these two. Maybe there was a producer connecting them, and I just thought that was so funny. That means in the lore of Strip Mall, Jerri Blank, all of those people are still existing if they got out of the fire. And that happens in Difficult Loves, the ruins of Trollhätan are bulldozed to make a strip mall. I was just really obsessed with images of malls, and malls as just this weird environment. Trying to have this European promenade, but they’re so American, obscene and bloated. It’s funny because now I feel like American malls are dying but if you go out of the country, malls are alive and well. Like in Korea and Japan there were so many malls. People still love a shopping stroll.

If Shriekers and Pebbles are two series you have going at the same time and both represent different kinds of thought processes or things you can turn into comics, what part of you that you’re not tapping into is like “I gotta bring back Stripp Mall?”

Stripp Mall was almost like a way to write a society experiment if people were trapped and couldn’t leave. There was something interesting to me about a society that all exists, it’s not even necessarily on this world, it all exists in this trapped space. I like constraints in writing, and malls can feel that way. I think the intention is you don’t leave, right? It’s like a casino. They’re trying to encourage a lapping pedestrian stroll and mimic a market, but it’s in this weird architecture. There is a really amazing mall story in Social Fiction by Montellier that I was like “Oh, she kind of already did it, and she did it really well, and it’s only like twenty pages.” I still have a bunch of material I wrote for it. It’s just a different voice and it keeps me engaged to try new formats. Pebbles has the consistency of this one character and there’s some mystery but there’s a lot of influence from my life. I think Lynda Barry calls it autofictionary or something, what is the term she uses? Autobiofictionalography. Some combination of taking images from your life but also twisting or adding other scenes or characters to it so it’s not too literally about you. With Stripp Mall, I just think … I’m sorry, I have no good answer to this because I haven’t started working on it yet.

Post-apocalyptic mall painting from 2016

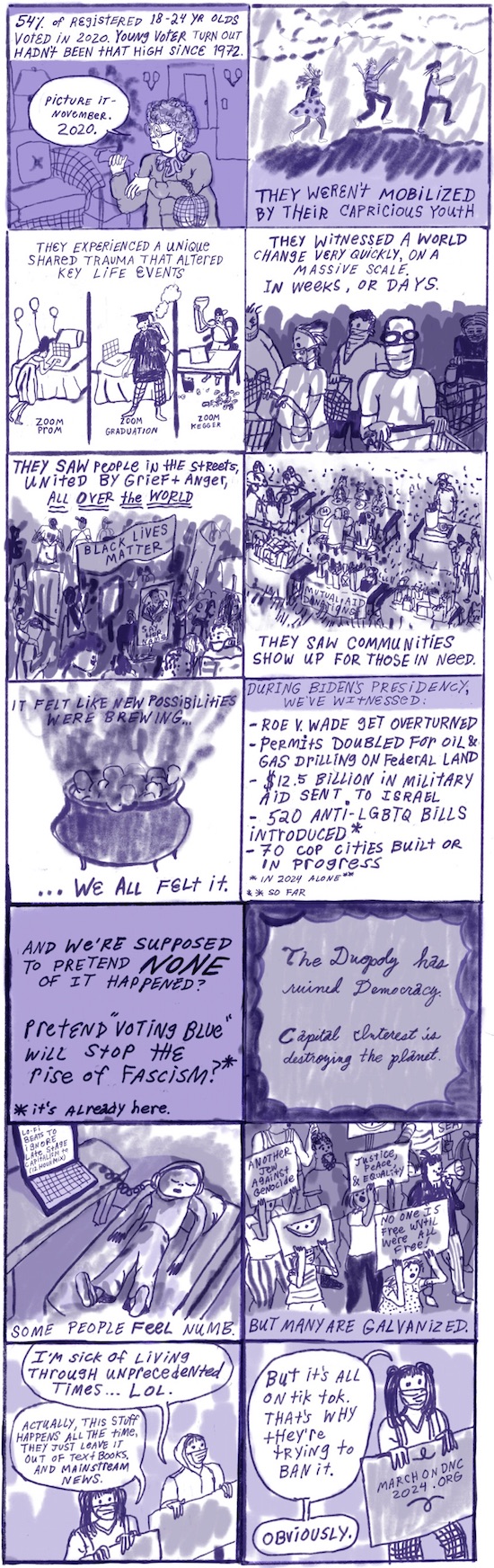

Post-apocalyptic mall painting from 2016 Political cartooning from Summer 2024

Political cartooning from Summer 2024That’s OK, let’s talk about other comics you’ve made. You were posting these political comics on Instagram. I wanted to ask if you regretted getting political at all.

No, not at all. I don’t have the stamina to keep doing them because as soon you start writing them it feels like that topic has passed. Those were written to be looked at on a phone and be disseminated. It was inspired in part by reading Dykes To Watch Out For and thinking about [how] Bechdel was making that at the same time as the projects she’s more known for like Fun Home and Are You My Mother. It's exciting to see what she was thinking about, just all the fucked up shit that was happening at that time that’s not in these graphic memoirs, but is a vehicle to talk about big box businesses taking over small bookstores or overhearing the characters' discussions as they’re going to protests. Really minute issues to big. I just kinda wished — I know so many cartoonists, and none of them will touch politics. There’s a lot of people who make political work like Eli Valley’s work and stuff like that, but I’m in a dense comics city and a lot of people I know here are not making work more explicitly commenting, so I wanted to try it because I can’t really complain about it if I’m not doing it. It was a satisfying way to remember making comics are artist’s therapy. It was a way to have these conversations I wasn’t seeing represented. Your gotcha is “Are you ashamed of not being for Kamala?” That’s not what the work is about to me. It’s like, why the fuck is it still a duopoly, why is that not frustrating to more people?

Well, I agree a duopoly is bad, but I think now we’re not going to have that anymore. I think now we’re at a one-party fascist state. Our politics are probably pretty similar, but the points of distinction are that the objections of even the very recent past seem quaint.

Of course. I didn’t have a specific aim. I wasn’t trying to not get Harris elected. I was just interested in having more conversations, because I think the distraction of the duopoly is why there’s this hamster wheel where we’ve been stuck for a few decades, where we have a little progress, then it gets much worse, but of course now it’s outsized.

I was interested in why, especially people older than me, Gen Xers or whoever, had lost any kind of ambition for a better representation of ourselves in government. Democrats didn’t get a real primary for two election cycles, that’s fucked. It was frustrating to see how many people were so disengaged. Also working with young people, seeing how nihilistic they were becoming, which I don’t necessarily blame them for, but was just frustrating. I was just trying have nuanced conversations through comics on the internet about that, but very quickly arrived at “OK, the only people reading these are people who pretty much agree.” It just started to feel like something I didn’t have the time to investigate more deeply. And it also just sucks making something for the internet. I was trying to think of, "Where are comics useful now and how can I frame these thoughts in a consumable way?" but it just became not interesting for me to make that work. I would rather do those in anthologies or something.

Have a newspaper gig.

Yeah, exactly.

Have you been doing political work outside of the internet in Chicago? Are there candidates running that you would support?

I was trying to be more involved in the alderman race that happened recently and supporting independent candidates by making lawn signs. Not all of the folks I wanted to win did, but there was much better turnout than they anticipated. The candidates almost didn't run because they were being harassed by …

The machine.

Yeah, the liberal centrist blues of Chicago gets pretty fucking frustrating. But a few passed through, that’s good. I feel like a lot of that work is through teaching.

Let’s talk about younger kids being more nihilistic. I feel like there’s a narrative of college students being extremely progressive but I talk to a lot of people who are like, “Yeah I don’t think that’s what’s really happening.” Or the politics are just sort of confusing. One of the things that came up in those comics was, “Let the younger people lead.”

Yeah, I think for a minute it felt like younger people were more engaged, and I think they were, and then they felt failed by elders and the system. I hate to make sweeping statements though, because I think that’s how those narratives shape themselves to be true. Because I still meet really motivated, so much more politically aware at their age than I was, people. There’s this ebb and flow where maybe they were at the right time where there were teachers able to be more direct in the classroom or expose them to more subversive material, because I always think growing up in the nineties, post-Reagan, I didn’t hear my teachers ever talk about how he fucked everything, you know? I learned about that through music.

Teachers don’t even talk about how they’re in a union and that’s the reason their life is OK.

Well, a lot of them aren’t anymore.

Well, not in Florida they aren’t.

Growing up in Florida, I was in a place off the path enough it was just wild. It was also close to an airport, they were flying over all the time. But there was also weird little ponds and gators. It wasn’t a gated neighborhood, all the houses were totally different. My Swedish grandfather who ended up there in the thirties, I have no idea what it was like then, but I think it was the middle of nowhere. He had one of the oldest houses in the neighborhood, and he designed it and built it with a few contractors because he was the son of an engineer, but an artist. He worked for Esquire magazine and was just building this beautiful … They had a conversation pit. Just a low house with a big yard and a garden. My mom was an only kid, her parents were artists. He built a house there and decades later my dad and my mom moved there too.

Your mom grew up in Florida?

She was born in Mississippi and they moved to Florida when she was a baby. She was born in 1945.

When were you born?

I was born in ’86.

And your dad was from Florida too?

Yeah.

This is a tough conversation obviously, but I did want to talk to you about the memoir comics you were making about your mom dying. I remember thinking that was something someone would offer you a book deal for, because people in the book publishing world love a memoir. And I felt like maybe you didn’t want to go down that road, especially for your first big book, and I feel like with Pebbles, you’re talking about these feelings that are huge, that you want to process but in a fictional way, where it’s not just about grief and loss, and it’s more fun and maybe more cathartic for you to work with.

There’s some truth to that. People did offer to print those. Not like, Pantheon. Someone did say, would you ever want to make a book of these. I just said, "Not now." It felt too raw. It was again an example of trying to process what’s going on, and my coping mechanism is drawing. It’s always weird sharing it on the internet, but there’s a catharsis in knowing someone is like, “Wow, you really got that right,” or “That is how that feels.” I lost my mom and several of my close friends lost a parent all within a few months of each other. So we were all having this kind of grief that you know is coming, but you kind of doubt at the same time. People tell me all the time I am too young to have lost a parent, but that is the deal I was given because my mom had me at forty, but also feeling like I still need to be parented, I still crave that relationship. We had a really complex relationship and it was weird knowing it was coming. It’s slow, but it’s also really fast, and people don’t know how to talk to you, so it’s also really lonely.

from 2021

from 2021I specifically remember thinking [a mutual friend] had lost her mom recently, but also you have sisters who would clearly be the people who would share your grief the most and understand you the best.

It also throws every relationship into flux, because you’re just in this fog of, I have to make it through the next day. And there’s this person that — you think you’re gonna have these big conversations, but then you don’t. And you’re just sharing space. It’s interesting talking to people about that because my mom just wanted the TV on 24 hours when she was passing, so to feel like everything was normal and numb, not having to deal directly with what’s happening, you know? And having to be like, that’s what she wants, but it also felt crazy, just being in this room watching Guy Fieri. It’s a weird time capsule where even if someone wants to reach out to you it’s hard to know …

Where to begin.

Yeah, so in a small way making those comics was a way to communicate, “This is how it’s going.” Because normally I would have more social interaction but it was a tough time.

It was during COVID.

Yeah, that too. Already seeing people way less. It layered a lot of anxiety I already had. Social stuff was even harder. I was like a zombie some days, teaching. I can’t believe I was teaching during a lot of it. Those comics were kind of a confessional way to say “I’m pretending everything’s [OK.]” I would be open to doing something with that work, but there’s not enough of it to warrant it being its own thing, and I’m not in a place right now to continue working on it necessarily.

Launching Pebbles and Shriekers at the same time, what are the factors that led to you having the urgency or confidence or whatever it is to … I feel like you’re really locked in, there must be some kind of switch that flipped.

You have to learn by making. It’s also just really important to make things you don’t share. I redrew Pebbles 1 three times, certain sections of it, because I really cared about the narrative, but I couldn’t get it. It just felt like no, this isn’t it yet. It was a story I really cared about. With comics there’s this consistent deadline of having something new, which makes sense, but it’s so easily consumed, but they’re so labor-intensive, so sometimes you put out a version that’s not its best self just to feed that demand. I just really didn’t want to do that. I don’t know, it probably had something to do with my mom passing. Well, if I’m gonna fucking make comics, there’s nothing like “life is short” like watching someone die.

But also you were like, 35, right? You were just at a point in your own adulthood.

But also I was at a time in my life where it felt possible to make comics. I have a consistent studio space. I have accumulated enough of a point of view to know how I want mine to look.

What is it about the earlier versions that were lacking?

I think one thing that really helped was not doing it in color. Because color is so important to me, and it dominates in this way. Working on Stripp Mall was just painting for hours, which I love to do, but it became less about the narrative and more about these visual images. And I think that’s the issue with a lot of my early comics work, I was hiding behind a lot of labor. These look like they take a long time, so maybe they're good? But I was nervous to put more writing or vulnerability into it, because I was still finding confidence in those areas. But I spent time working on narrative through other mediums. There was a time I wanted to be an animator.

Did you do much animation?

I’ve done some shorts like stop-motion. I did a really dumb Stripp Mall animation but it's not as complex as the comics. It was important to me to try all these things out, find out what I liked about them, and then come back to comics, appreciating comics for the value you have in world-building, but also you have [to have] economy to get out enough of a story that people can hold on to. I was doing videos, but I’m not a director. I like performing, and that scratches the writing brain, and you become a better writer for a character by embodying characters. I think those were ways to play and figure out things I’d perform in order to just write better. It’s just also about reading lots of different kinds of comics, what drives me to keep reading or spend time with work. But a huge thing was just switching to black and white, because I realized that at least at this point, working in color was kind of silly.

Two things I feel are very evident in Shriekers and Pebbles, and if you were to be like, “Oh yeah this is what drives me to keep reading a comic” I would understand, are humor and depth of character. Both those things are very present in those works but also I feel like there aren’t a lot of comics that do that, from my perspective. What are comics that you think are really funny and what are comics characters that you find really compelling and deep?

I think Samantha Szabo’s comics are so funny and written so it’s joke after joke, delivering a lot of jokes per page. For depth of character, it’s Los Bros [Hernandez], right? Hard to beat. There’s something also too about living in Chicago, it is a much denser comics community here and getting to see how a lot of different people work and their process is really inspiring. Like Anya [Davidson], Conor [Stechschulte], Lane [Milburn]. Honestly, for humor, I don’t really go to comics.

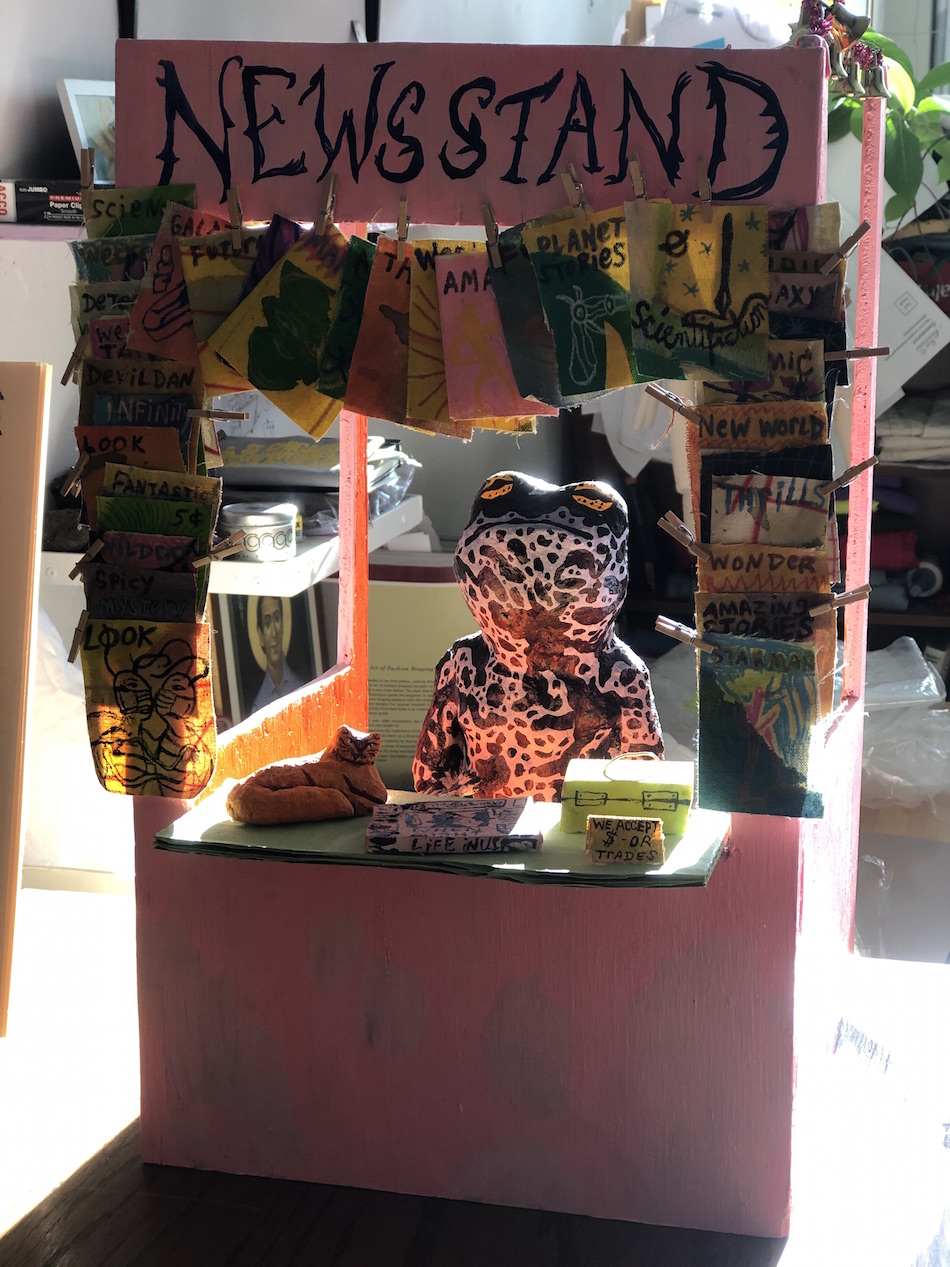

Miniature newsstand from Gridsport, photo by Kevin Huizenga

Miniature newsstand from Gridsport, photo by Kevin HuizengaIs there something also like, “What I’m really coming to comics for is great drawing,” because that’s also something your comics have in spades? What do you think keeps you reading comics when TV shows are funnier?

The abstraction and they’re often a little bit ahead of the culture because they’re able to explore an idea without a huge production value. Like Ines’ [Estrada’s] Alienation, I think is so good, in that there are bastardized versions happening now, but that book came out at least ten years ago. The Eternaut.

I haven’t read that. What’s good about it?

It’s able to channel a mood, you can really enter the comic, into the place where you’re visualizing. You’re having this sensory experience through someone’s hand. I just devoured Mimi Pond’s Over Easy the other day, so good. It’s actually pretty funny, there’s funny moments in that. Pebbles was also inspired by reading a lot of weirdo manga that has a really loose sense of time, like Kuniko Tsurita, who was inspired by French New Wave films. They are often so short, but they’re really slippery stories. I feel like films sometimes are too long for the concept they’re trying to convey, and I feel like comics, the way the pacing is set up or the variation in their length that feels like it was meant to be in that format, the rhythms of text and image just work.

The issues of Pebbles keep on getting longer, so I wanted to talk you about the overall structure. How long do you see it being as a book, and are you in in the middle of the next chapter now, and how long do you think that’s gonna be?

For now the plan is for it to be five issues and end in five, but that depends, can you land the plane in five? I think I can. I do like that they get longer in each one. There are a lot of funny little challenges in writing it. Like the second one is twice as long as the second one, so I was like ooh, it would be cool if the third one was twice as long as the second one. So it would be cool if the fourth was twice as long, but that’s a lot. But maybe, I don’t know. It’s looking plausible. Right now I’m in the writing/panelling phase.

What’s your process like? Is it thumbnails with a lot of dialogue? It feels so visually driven.

It goes back and forth between text and images. Echoes between the two. There’s a lot of writing exercises. Especially since it’s not in linear sequence. So sometimes I’ll write something out then move it around, or realize this needs a beat before this. There’s a mix between intuitively following where the story’s taking shape and definite mapped items. The exciting part of writing is figuring out how to get from this to this and leaving a little to be found on the way or through serendipity, or, “Oh I didn’t even realize this was in issue one.” I feel like that’s why I wanted to serialize it. I didn’t want it to be one dense thing. There’s something exciting about having conversations about an issue and then some of those help fruit the story. That’s part of why I was doing Shriekers back to back too, so I could sit with the material longer and see what was there that wasn’t apparent in the beginning.

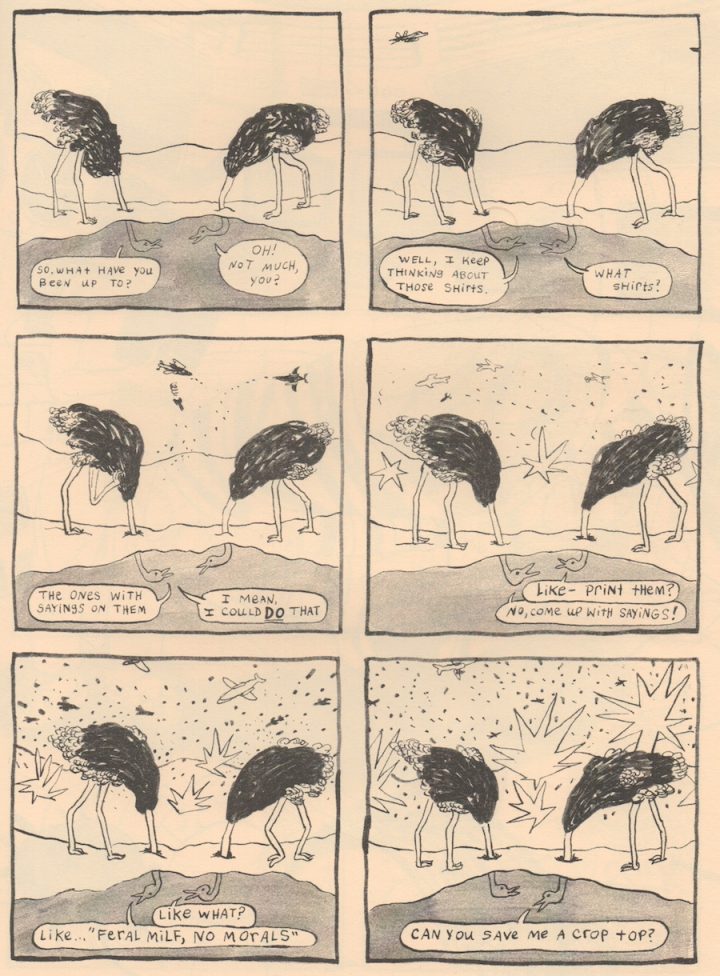

What came first, the "Feral Milf, No Morals" t-shirt, or the conversation in Pebbles 1 where the ostriches are having a conversation and one says they could come up with the sayings for t-shirts, like “Feral MILF, No Morals”?

The comic came first.

Page from Pebbles 1, published 2023, where the germ of a t-shirt idea was born

Page from Pebbles 1, published 2023, where the germ of a t-shirt idea was bornAnd then you were like, that would be a great t-shirt.

Yeah. Exactly. Bless that t-shirt. It’s been a great way to talk to people. People buy them for their in-laws, or are like, “Oh I have another friend having a baby, I need another 'Feral MILF No Morals' t-shirt.” There was moment when I was gonna make a bunch of them, gonna riff on every kind of milf.

Look, I straight-up don’t think people should identify as MILFS, because the “I” does not refer to their own self-conception, but also Feral MILF No Morals, that’s not a lot of people. Most people buying that t-shirt I think actually have a lot of morals probably.

But it’s not just that. I don’t have children, right? Don’t plan on it. But I’ve watched a lot of friends be pregnant, and sisters be pregnant, and there is something about a pregnant body that makes someone into an extreme version of themselves. Maybe they have morals once they’ve long forgotten that period in their life, but there’s so much of pregnancy that you are not in control of. It’s grotesque at times. I was present for and filmed my best friend’s birth — it was terrifying, but also empowering. It was a natural birth and she was walking around covered in blood. It was like a horror film. And there’s something that changed for me, meeting people who have kids, where I’m like, but you were this being.

You hosted the xenomorph.

Yeah, and you pushed it. Like, I’ve seen how big a placenta is. It’s such a more animal experience than we give it credit for, maybe because there’s such a sterile version of it now. You just pass out and they grab the thing. I also love the people who buy it who are not moms and are just like “this is me,” and I love that self-specification people can have with drawings. I know if someone’s gonna buy it immediately by the way that they run up. And you are right, there are a lot of lookie-loos who are like “I just don’t know if I can pull it off” and it makes me feel a little bad for them, because I sense that they want to. My favorite is when women are like, "yeah, I wear it to the farmer’s market every week, I wear it to pilates." Because I like a garment that says you’re safe to be fucked-up and weird with me, an instant wink at someone who identifies with that sentiment.

Page from Preguntas, 2011

Page from Preguntas, 2011

English (US) ·

English (US) ·