Tate McFadden | August 26, 2025

Simon Hanselmann is one of the best working cartoonists in the world right now. He’s an auteur, having written Megg & Mogg for several decades, crafting a world of surreal, depressing debauchery. Even at its most naturalistic, Hanselmann’s work is startling in its weirdness. The stories revolve around the hijinks his cast of characters get up to, typically in search of or in consequence of a high. His characters include: Booger, a trans woman covered in, well, boogers; Megg and Mogg, a witch and cat in a failing romantic relationship; Owl, an anthropomorphic owl; and Werewolf Jones, an addict werewolf and neglectful father.

Although he has been a fixture of the indie comics scene for decades, self-publishing zines from his hometown in Tasmania before moving to the U.K. (and later the U.S.), Hanselmann’s popularity soared during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic when he started publishing the Instagram comic Crisis Zone, which satirized the cultural hellscape of the lockdown era. His cast of ill-adjusted, drug-addled characters reacted poorly to the pandemic to say the least, as Hanselmann amplified the manic energy of Tiger King tenfold.

Hanselmann’s latest installment in the Megg & Mogg saga, You Will Own Nothing and Be Happy (YWONABH) shares some parallels with Crisis Zone, and is perhaps his most conceptually ambitious piece yet. YWONABH sees Megg, Mogg, and Owl trying to survive a zombie apocalypse. At four issues and counting, the series is some of Hanselmann’s most desolate work yet. But despite the post-apocalyptic setting, YWONABH has a quiet calm that is new to Hanselmann’s work. Previous Megg & Mogg stories occasionally indulged in a similar quiet: Megg might sit for a moment alone, contemplating her depression and fears, but her rest is consistently interrupted by the raucous, inebriated interjections of her criminally inconsiderate friends. In YWONABH, these moments take center stage.

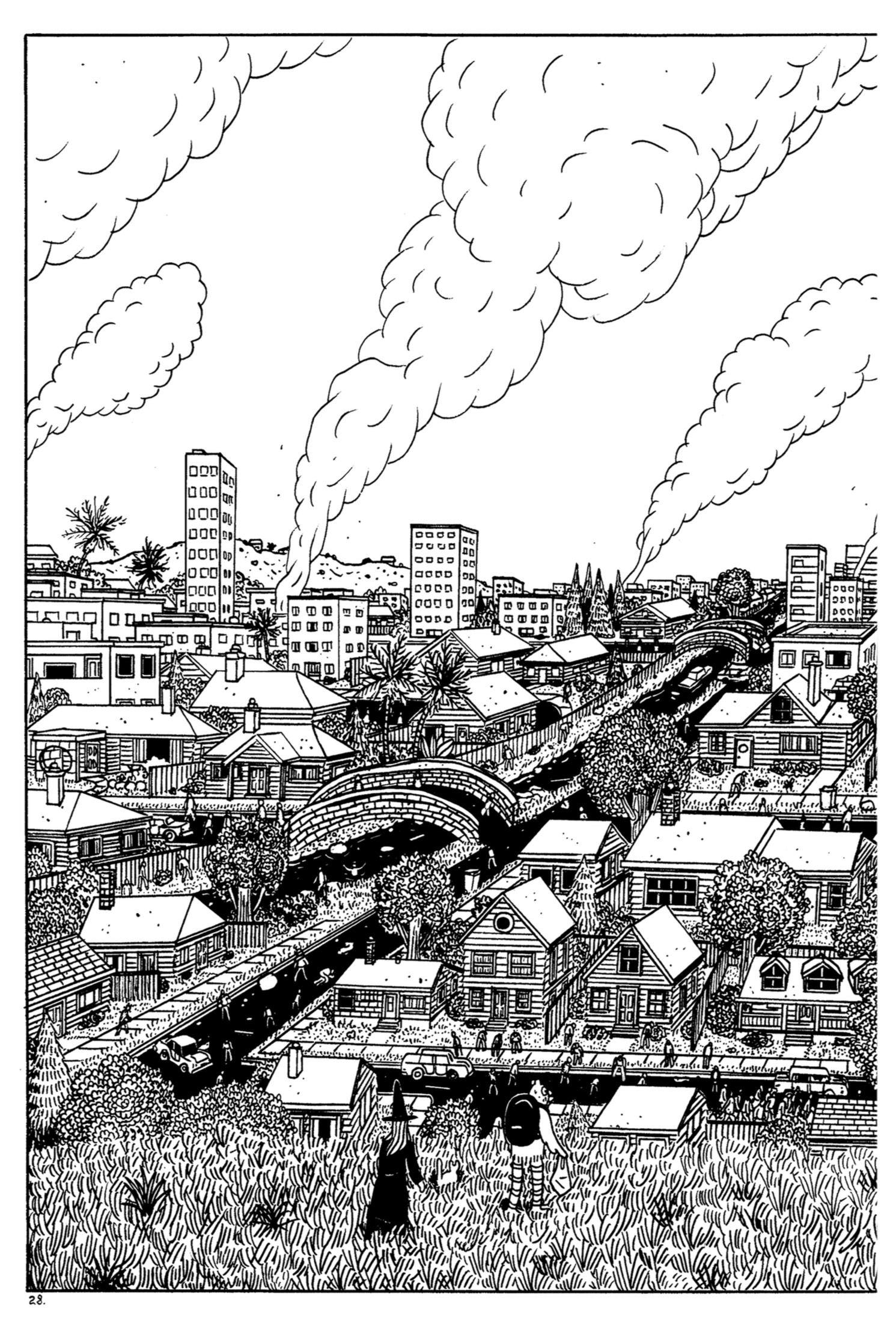

Despite being drawn in black and white rather than Hanselmann’s classic watercolors, YWONABH’s pages are lush, packed with stunning splashes and wide shots in which Megg, Mogg, and Owl wander the streets of a decimated world. Such moments are sublime, driving home an undeniable seriousness to what these seemingly ridiculous characters are going through. Many of Hanselmann’s paintings have a similar feeling but normally they exist outside of the action of a story, relegated to front or back matter.

Megg & Megg is so often beholden to the standardized grid structure — Hanselmann has said he “believes in the grid" — that departures in layout are often few and far between. YWONABH feels a bit more free-form and loose, as if the calamity that has befallen the world is so great it’s broken through the bounds of the grid itself. The stakes are far higher, with very real and immediate danger to the characters, but at the same time all of the worries which once plagued them are gone.

The zombie apocalypse’s strange ability to break the typical structure of Megg & Mogg extends to the story itself. Most Megg & Mogg stories are driven either by poverty, addiction, or trauma. In YWONABH, the first two are obliterated by the zombie apocalypse, and the latter takes on a new, more violent dimension. You can’t have a zombie apocalypse without traumatizing a couple of characters, and in YWONABH, trauma comes in spades. Unlike in other Megg & Mogg installments, however, the world won’t let Megg, Mogg and Owl stop and dwell on it.

Megg & Mogg storylines largely take place on a cruddy couch in a disgusting house, where its characters get depressed, high, and then depressed again. Crisis Zone was the series' first story that featured consistent, fast-paced action. Crisis Zone and YWONABH both force their characters to face down the horrors of a global meltdown. Crisis Zone relies on absurdity to make its action land (Tiger King parodies called Anus King, or a jaunt through the Portland Autonomous Zone). Characters try to process the traumas of the pandemic but are constantly being swept up in the loud, frenetic action.

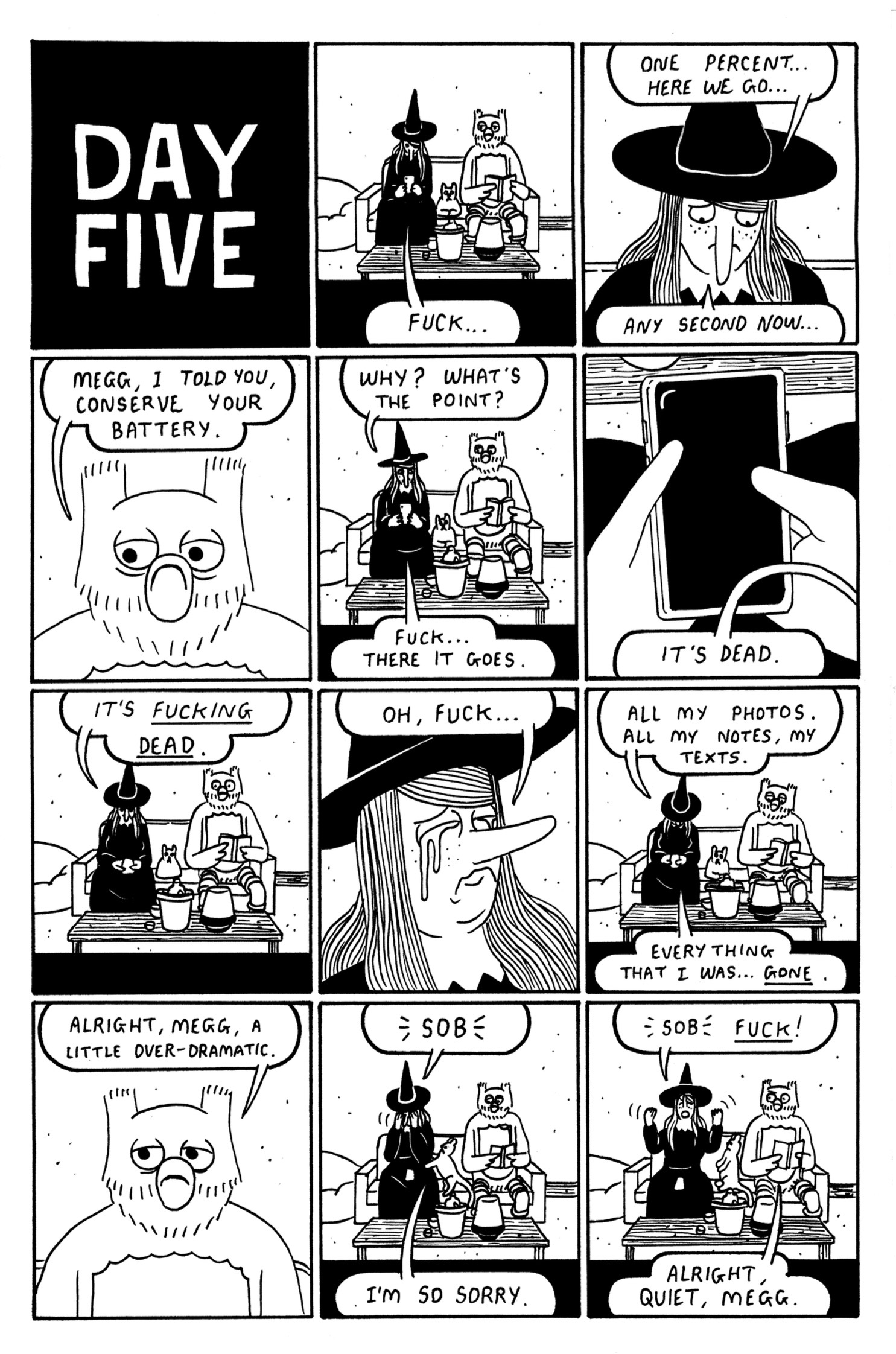

In contrast, YWONABH is deadpan, and thus horrifying in a wholly new way. Hanselmann pares down his cast to just Megg, Mogg and Owl, removing the characters that made Crisis Zone such a wild ride, chiefly Werewolf Jones. The vices are gone as well. In issue one we see Megg process the loss of the internet when the power grid shuts down, and weed when she smokes their last bowl. This occurs in Crisis Zone as well, but it’s played as Megg being childish, as she whines about her "Animal Crossing" game not arriving on time.

In YWONABH, the loss of the internet is serious, existential. When Owl tries to pass Megg’s terrified tears off as an overreaction, she stares at him saying, “It’s all of history, Owl! Our connection to each other! It’s all gone! Everything’s gone!” to which he can only sigh and reply “I know … I know.”

No matter which book you’re reading, all Megg & Mogg characters are more complex than their cartoonish concepts let on, but the cast is for the most part stagnant. The strength of Hanselmann’s writing is his ability to plumb the depths of his characters’ inert, damaged psyches. What’s so horrifyingly fascinating is their utter unwillingness and inability to change. The premise of YWONABH forces its characters to change and develop.

During the zombie apocalypse, inability to adapt means death. In the most brutal scene I’ve seen from Hanselmann, one of the trio is sexually assaulted and another is killed. Megg, Mogg, and Owl become killers in order to survive. Issue four, the newst issue as of this writing, is about the survivors grappling with the trauma of their friend’s loss and their newfound willingness to kill. It’s a classic arc for zombie fiction, but because we’ve had so many books to get to know these characters in the "normal world," it comes as an intense shock. It’s refreshing to see the Megg & Mogg cast, whose problems are human and real but largely cartoonish, trimmed down and made to develop and grow, even within the setting of an apocalypse.

Hanselmann has been attempting to write Megg’s Coven, a book about his mother and her problems with addiction through the lens of Megg’s relationship with her own addict mother, for years. In the author’s notes at the back of issue four (Hanselmann’s author’s notes and letters columns in YWONABH are excellent and extensive), he writes, “I’m just still not ready to engage with the Coven material yet. I can’t face it. ... The whole situation just depresses me. The sadness and anxiety is overwhelming at times. Mostly I blame the drugs. They robbed her of a real life, robbed her granddaughter of ever knowing her, robbed me of a strong parental figure.”

Hanselmann has been incredibly open about discussing his difficult relationship with his mother, and how hard it is for him to write about it. He’s referred to it as his Winds of Winter, George R.R. Martin’s famously long-awaited sixth Song of Ice and Fire novel.

It’s nearly impossible, especially if you’ve ever confronted addiction in some way, not to see the deep emotional care Hanselmann takes with so many of his comics, even at their most hilarious and oddball. YWONABH isn’t Megg’s Coven, but it marks a tonal shift in Hanselmann’s work, one towards an even more thoughtful sense of characters and relationships.

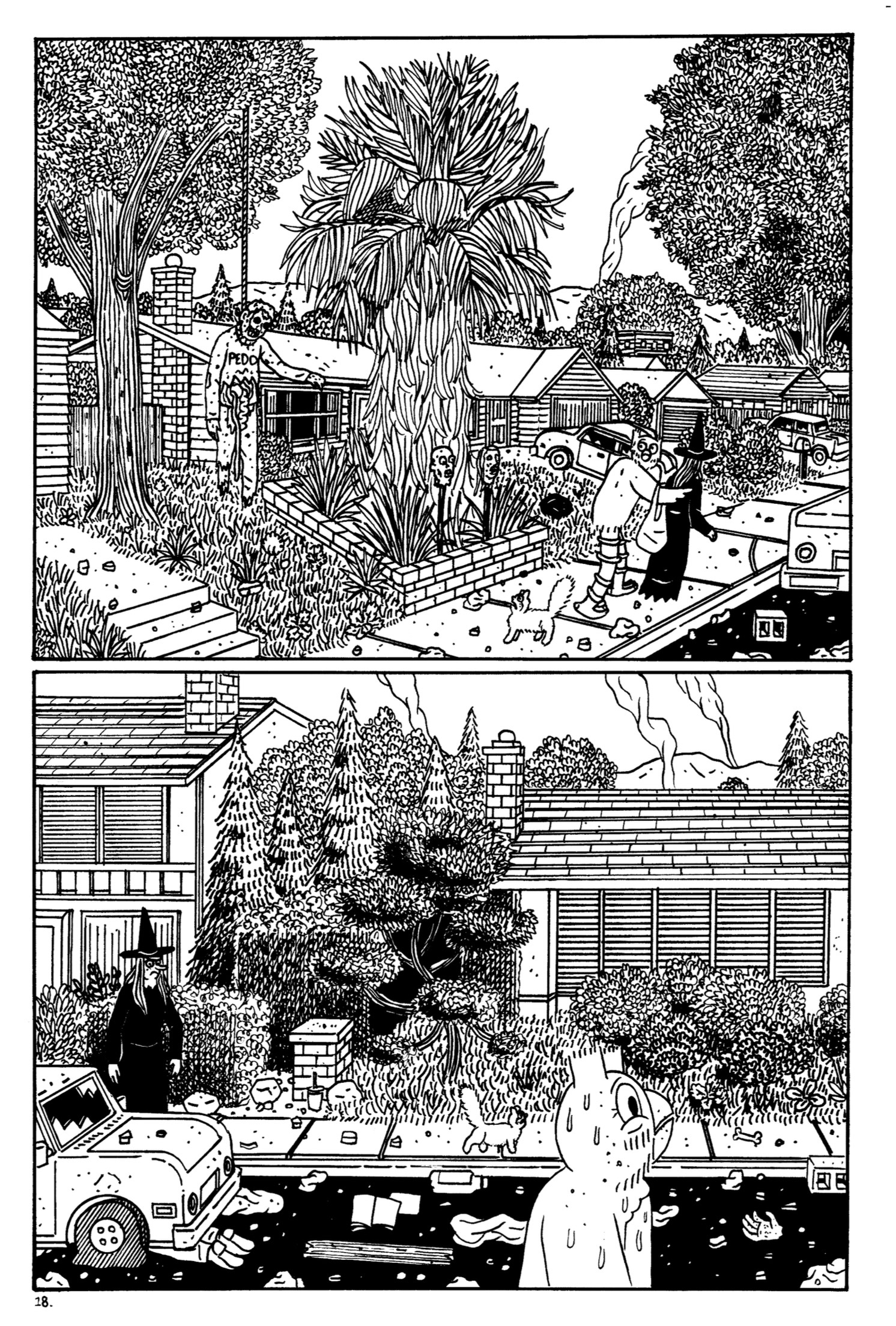

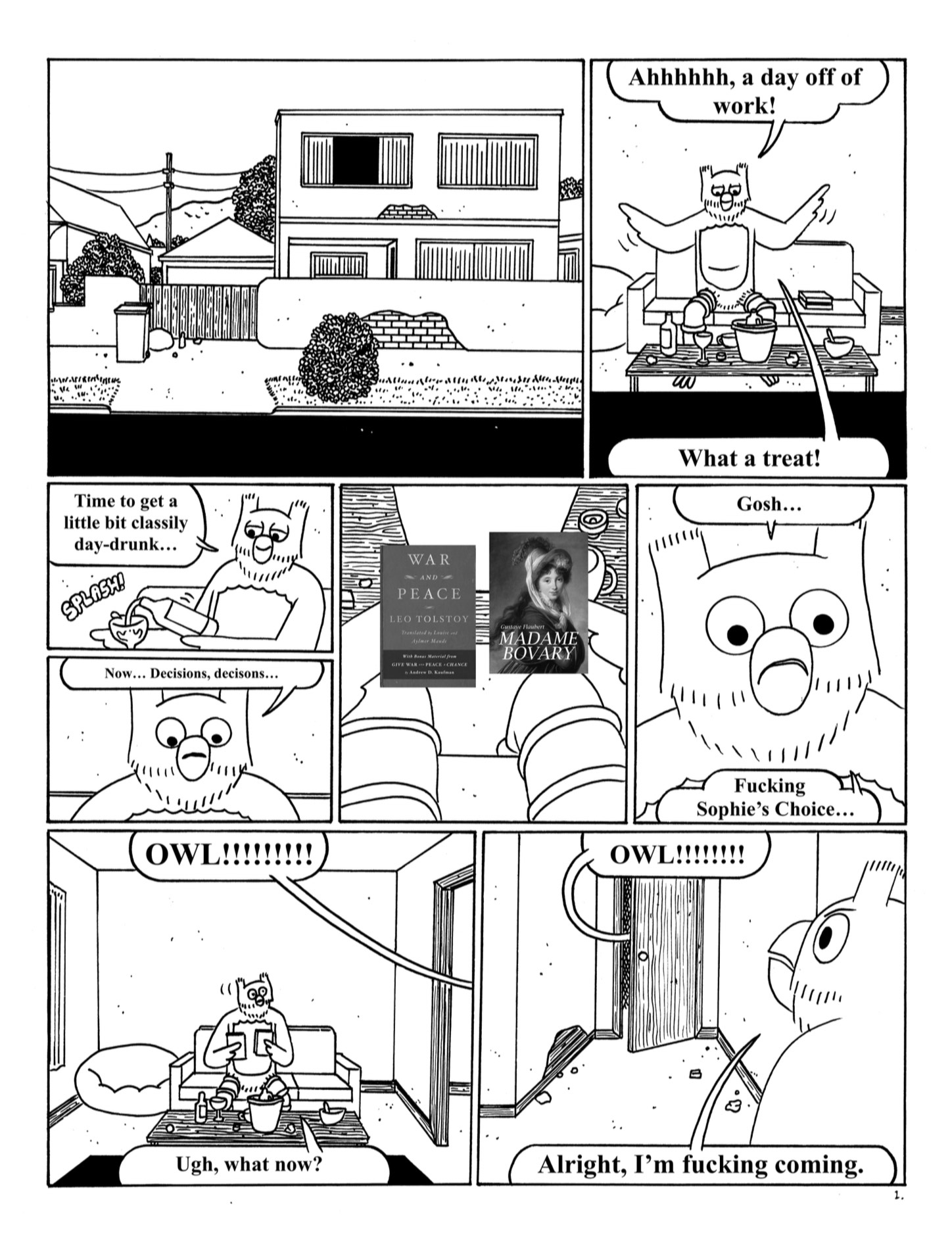

If YWONABH is a new kind of brutal for Hanselmann, Boys in Prison, which was self-published by Hanselmann and originally distributed at a talk he gave to the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) celebrating the tenth anniversary of his Megahex collection before being distributed by more broadly, proves Hanselmann can still dish up a raunchy, disgusting, and pearl-clutchingly violent comic.

Boys in Prison is a short zine following Owl as he tries to pick up fentanyl from Werewolf Jones for a sick Megg and Mogg. Quickly, Owl gets roped into the violent exploits of Bazza, Jones’s dealer whose supply of fentanyl was just stolen. Together, the trio hunt down the yakuza who stole the pills. The adventure soon takes on a familiar structure, in which uptight salaryman Owl becomes increasingly freaked out as he gets sucked deeper and deeper into the debauched lives of his friends.

During their misadventure, Bazza repeatedly has sex with men he’s holding at gunpoint, all the while insisting he’s not gay, he “just likes sex.” It’s a recurring refrain in the comic, and one which you don’t often see in Megg & Mogg stories. Typically, people fuck who they want to fuck, unconcerned about gender, relationship status, or general cleanliness. Hanselmann is a master at creating unflinching portraits of sex and sexuality that poke holes in any number of the legion preconceptions that people take for granted on a daily basis. Maybe it’s schadenfreude, my own queerness, or maybe it’s the gender theory talking, but it’s fun to watch a character as violently masculine as Bazza be so insecure about getting a blowjob from a man in a bathroom.

Boys in Prison also presents a novel role for Werewolf Jones, who is normally the instigator, but this time takes a passive role, upstaged for the moment by Bazza. The story isn’t new territory for Hanselmann, although it might feel more novel if he hadn’t published Below Ambition, which was greeted with unsurprising outrage for its vileness, a couple years prior.

Boys in Prison is a classic Megg & Mogg story, albeit a little more violent than the norm — you might see it in a collection of his work a few years from now. If you’re already a fan of his work, you’ll likely enjoy it, but as an introduction, it can be pretty harsh.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·