Tom Shapira | January 6, 2026

I believe I break no new ground by announcing my favorite part of Sammy Harkham’s Blood of the Virgin was the cowboy actor interlude (originally published in Crickets Color Special #1). The rest of the book I can take or leave, a work that brushes alongside greatness without ever achieving it, but that particular chapter was something else. Not just the best-looking part of the book — Harkham has such a skill with color that a black-and-white page by him almost feels like a fundamentally bad choice — but also the one that best utilizes the medium of comics. A story stretching time and space in a playful manner while still delivering the emotional goods.

Maybe you need the rest of the book, downturned and downhearted, to make this one-part stick out more? Nope! A diamond shines just the same, be it in a pile of garbage or a pile of other, lesser, diamonds. As if to make the point, the largest chunk of Crickets #9, the latest issue in Harkham’s one-man anthology, is dedicated to a new color story featuring cowboys and criminals. That diamond sure shines brightest.

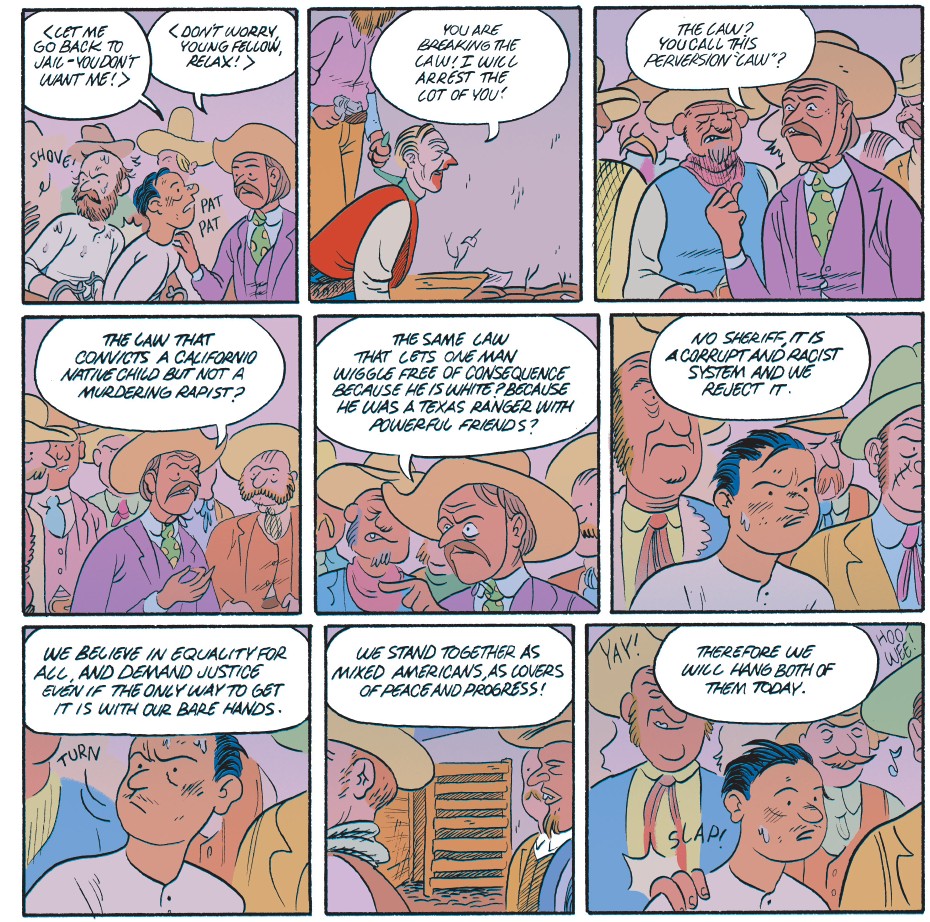

It's the first in what appears to be a new, long-running serial, though the story in this issue stands pretty well on its own, “The San Fernando Kid” concerns a Mexican teen called Alverez in 1865 California ("Alverez” being to California as “Smith” is to Boston, as the prosecutor mentions). Convicted for murder and locked in the same cell with a white man called Brown (also on the line for execution), Alverez is busy planning his escape as the gears of law and order prepare to grind him into fine dust.

For the first half of “The San Fernando Kid” is a well-observed Western fiction, presented with Harkham’s usual flare for expressive cartooning. Check out the scene with the sheriff trying out a cigarette via a series of whizzing and coughing, sounds that can patricianly be heard across the page, all contrasted with Alverez’s stoicism — we see his face twice and the back of his head twice more in the scene and even though the lines Harkham draw on him barely move you can tell exactly how annoyed he is. In its description of this environment and the people that inhabit it, “The San Fernando Kid” reminds me less of any particular Western film, and more of an early Elmore Leonard story. It’s not flashy, it has all the expected elements of a Western — the sheriff, the hanging judge, the prison escape, the train fading into the distance — but it never tries to simply replicate iconic moments for their own sake.

Harkham actually creates an entire world in miniature in these few short pages. While Alverez is the story’s focal point there is enough life to the people around him — the surly Brown, the taciturn old Sheriff, the slowly boiling-rage of the townspeople — to allow each to be the star of their own story. It's an interesting counterpoint to the main story in Blood of the Virgin, in which we had so much time to spend with fewer characters, yet our understanding of them remained the same throughout. It is possible the Harkham, like many of the cartoonists he idealizes, works best in short bursts rather than in a marathon storytelling session. If all “The San Fernando Kid” gave us was this little piece of observation on a period that had long become more of an icon than a perceived reality it would have been enough. But it gives us more.

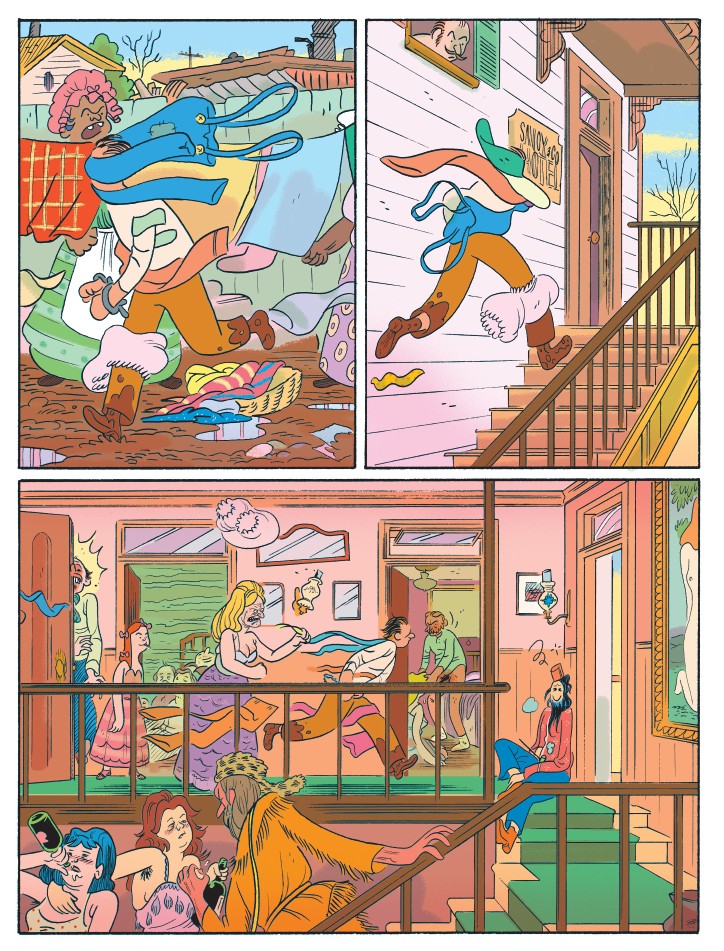

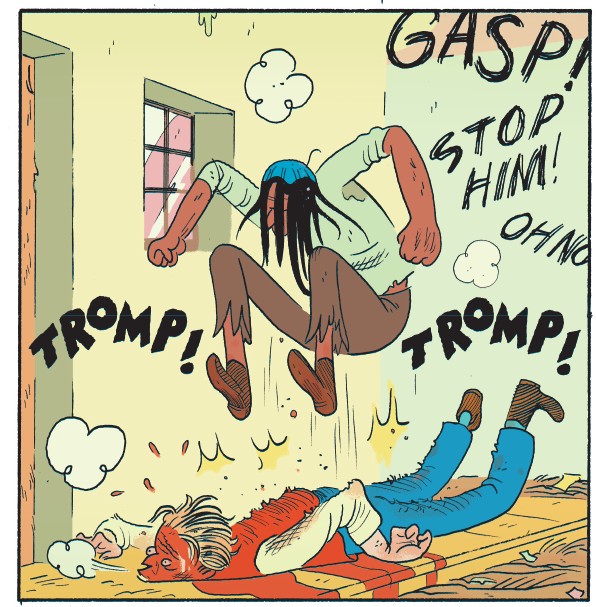

The final half of the story is a long, well-choregraphed, and extremely busy chase scene. It involves dozens of individuals, scaling fences, falling off buildings, hanging by a thread, dropping in manure, punches, shootouts, stabbings, kicking and screaming. It’s like the best of Buster Keaton freneticism meeting the Coen Brothers at their cartoony highest. It slides from comedy to violence to violent comedy at the blink of an eyes. It starts out strong; witness a panel depicting another prisoner stomping on a lawman like Mario jumping on the head of one of his enemies, a balanced panel — the sheer kinetic energy expressed makes it funny, but at the same time the pool of blood and the lack of expression on the face of the jumper adds an element of actual human pain. The man on the ground won’t be getting up again. It takes true skill for an artist to hit just the right balance, a bit too light and scene becomes unmoored from the reality the preceded it, a bit too grim and it becomes tasteless bloodshed. “The San Fernando Kid” hits the sweet spot and keeps on it for the rest of the issue.

Everything that follows is a cascade of violence that soon forgets its origin. It might have started as a well-targeted lynch mob (as well targeted as a lynch-mob could be) but soon the violence is everywhere. One could almost make an observation on the nature of violence in the American frontier, a place in which the law is more of suggestion than an accepted fact, and how much of America still carries on this pro-vigilante ethos … if one wasn’t too busy laughing and cheering at level of craft involved. This is "fun comics" and "funny things," two things that sound easy and yet (judging by much that I read) are difficult to achieve. That’s what makes the Keaton comparison compelling to me: here is a man that works hard, harder than anyone else, all in the service of a smile from the viewing public. Someone like Geoff Darrow needs ten thousand lines to sell this kind of gag. Harkham is good enough to make it with a few dozen.

There’s something joyous about this story, something old-fashioned that never falls into the pit of sheer retro. Whether future issues of Crickets can carry-on with this level of energy and style is a question for a different time. It is quite possible that this type of story isn’t sustainable long term. Even if the rest of the story falters, or if Harkham never comes back to it, “The San Fernando Kid” is worthwhile on its own terms.

I’ve mentioned that the rest of the issue isn’t quite up to par with “the San Fernando Kid,” but I should positively mention “Frederic the Great,” a play on these grand historical romances that ends with an effective joke. “Reunion,” meanwhile offers very little, reading like something Philip Roth left at the back of a drawer. Skillfully-drawn as it is, it reminds why I couldn’t fully commit to liking Blood of the Virgin. Harkham's best work tends be his vibrant and energetic tales. Here he plays everything down and the result is as stodgy as the lives it depicts.. The connecting thread throughout these stories, a violent end mixed with humor, doesn’t read to me as intentional (the lowkey grimness of “Reunion” has little tonal similarity to the joke-y final of “Frederic the Great”), but proves that if nothing else comics is still the best medium for death-as-a-violent-punchline. It's mixing the "adult" concerns of contemporary comics with the lowbrow mayhem of their artistic forbears. No matter the time, no matter the place, in Crickets #9 everything ends in death. Followed by a gag.

Whether one takes it as some philosophical statement, or just a byproduct of Harkham’s sum of influences, Crickets #9 can sit proudly on anyone’s shelf as one of the best comics 2025 has to offer.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·