The Editors | December 23, 2025

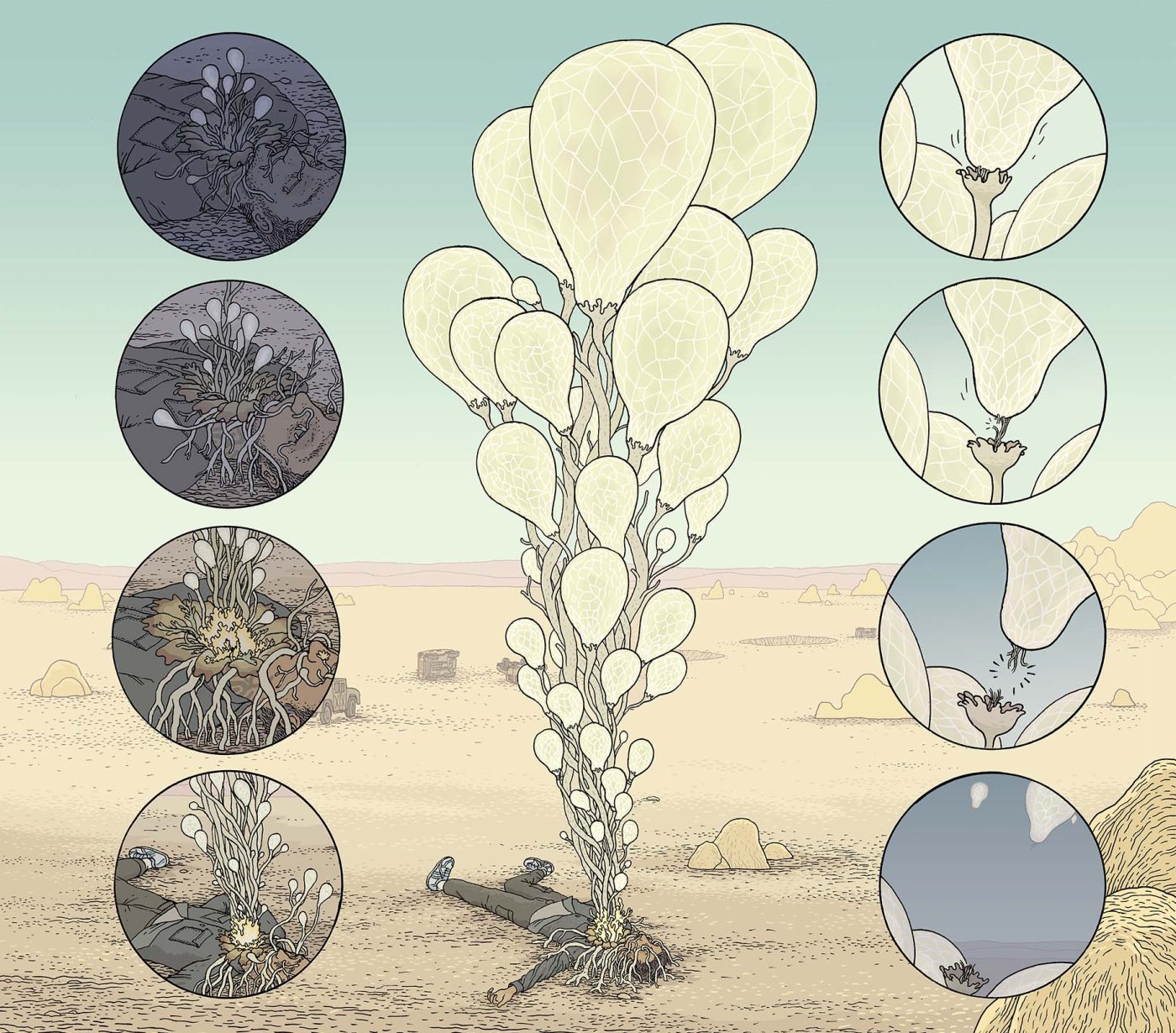

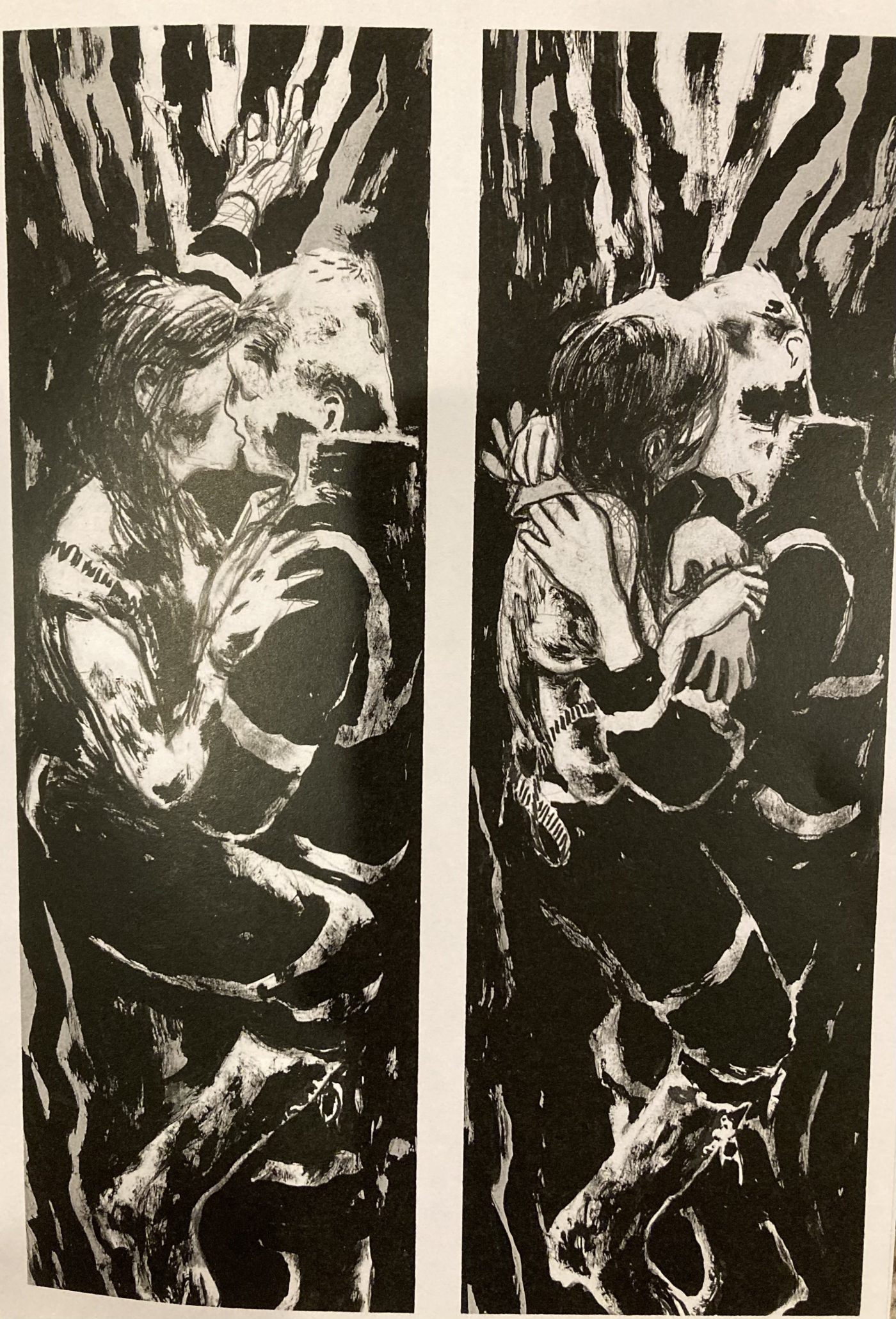

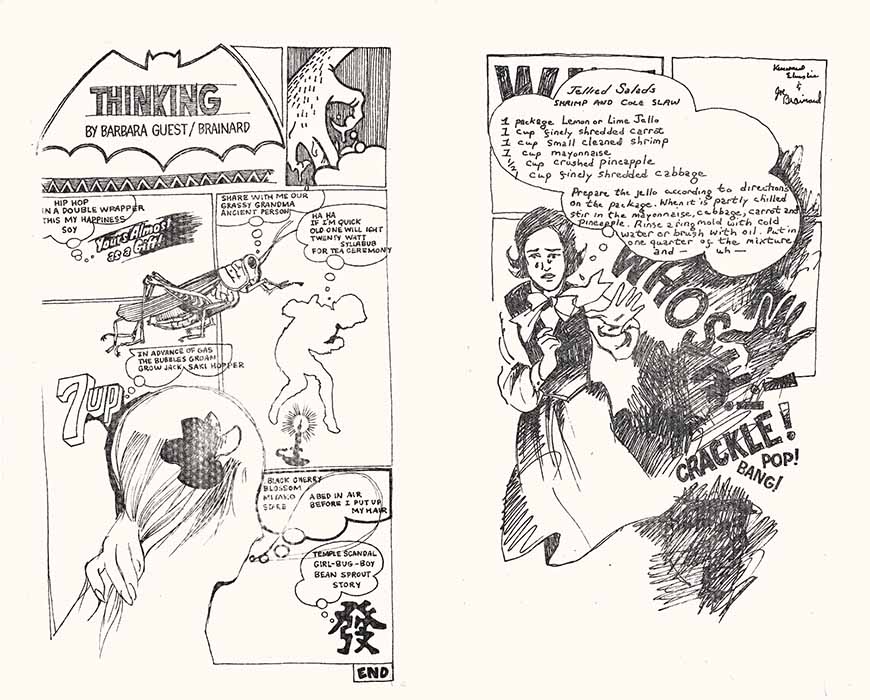

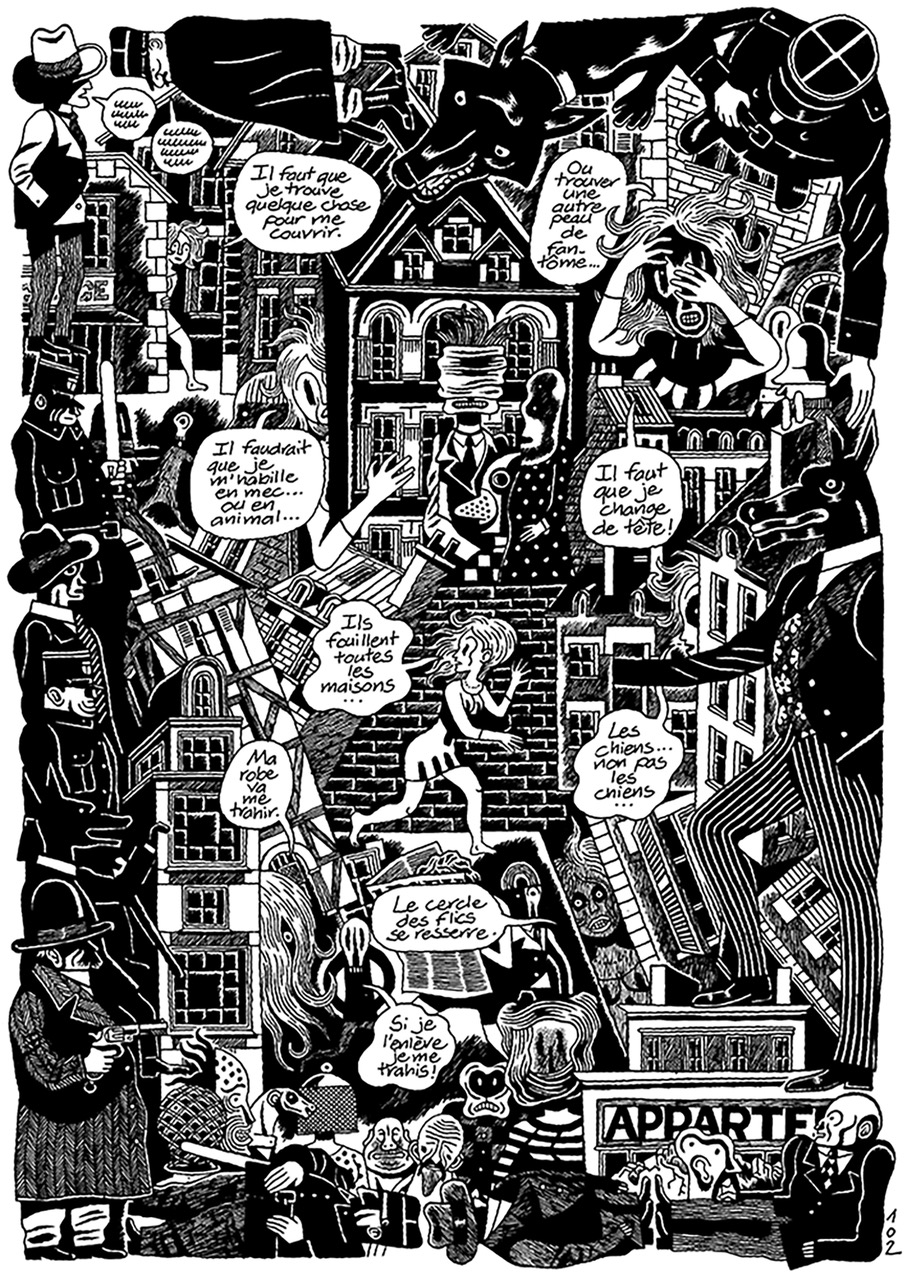

A fold-out spread from Tongues.

A fold-out spread from Tongues.We both know the history of superlatives creates a flattened, reductive interpretation of our world. But they're also the quickest way to label a praise for those recommendations we give in order to connect with one another, and isn't that why we're here? To find something in common, to stave off the loneliness for another hour?

Should you have any additions, questions, or qualms: treat yourself by commenting below. We'll be seeing you in 2026.

— The Editors

Contributors

(Click on a name to jump to their selections)

***

Jean Marc Ah-Sen

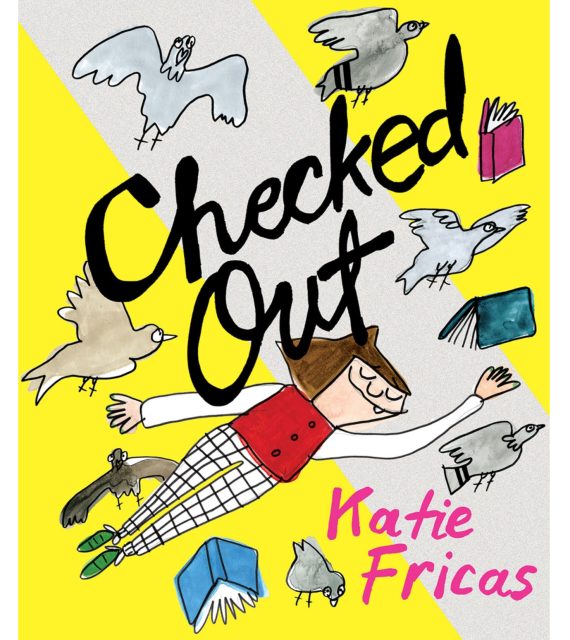

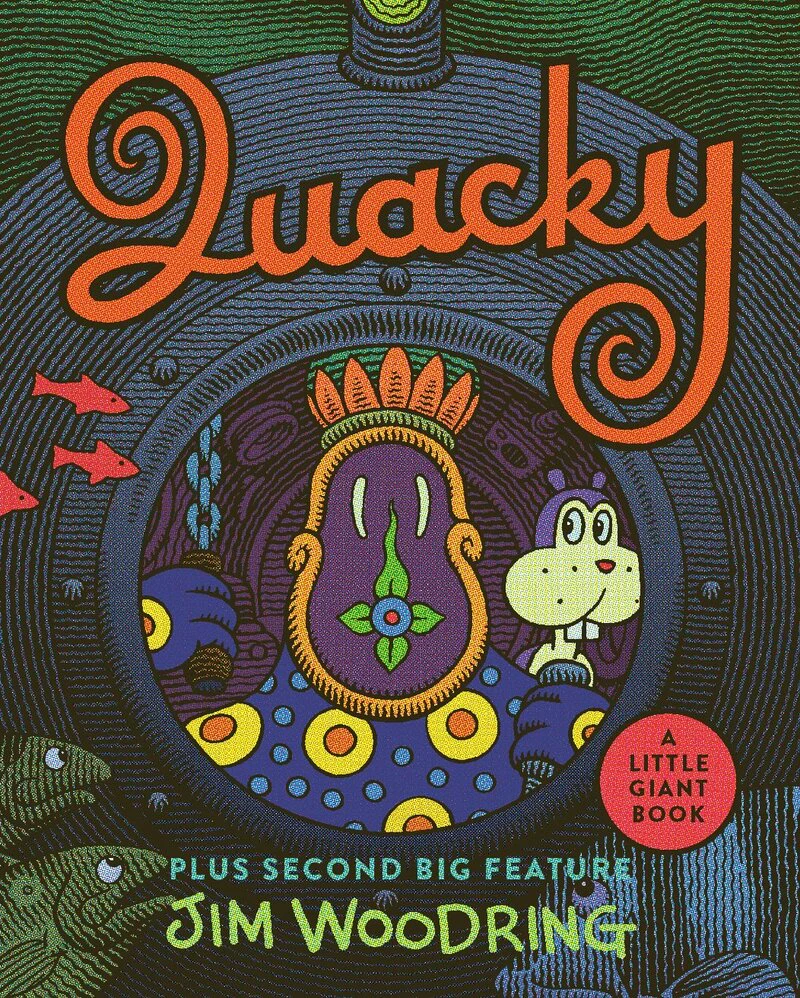

My favorite comic releases and reissues of the year, in no particular order:

- Pulping Vol. 2, ed. Jenn Woodall, Jon Iñaki, Jonathan Rotsztain, Mitch Lohmeier, and Paterson Hodgson

- All Negro Comics: America’s First Black Comic Book, ed. Chris Robertson

- Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers: Times of No Money The Early Years, Gilbert Shelton

- Jim Starlin’s Dreadstar Omnibus Vol. 1, Jim Starlin

- Untold Legend of the Batman 1, Len Wein, John Byrne, Jim Aparo

- Tsunami, Ned Wenlock

- Terminal Exposure: Comics, Sculpture, and Risky Behaviour, Michael McMillan

- Galactic, Curt Pires and Amilcar Pinna

- Holy Lacrimony, Michael DeForge

- Artificial, Maria Llovet

- Cornelius: The Merry Life of a Wretched Dog, Marc Torice

- Skinbreaker, Robert Kirkman and David Finch

- Absolute Martian Manhunter, Deniz Camp and Javier Rodriguez

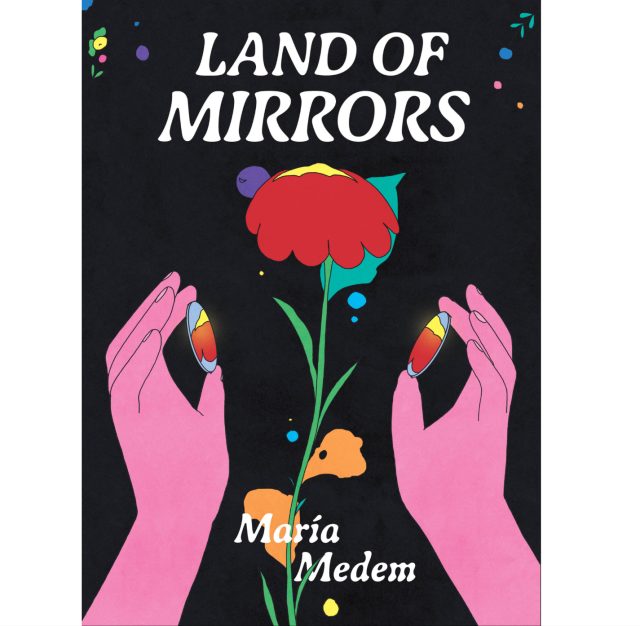

Land of Mirrors, Maria Medem

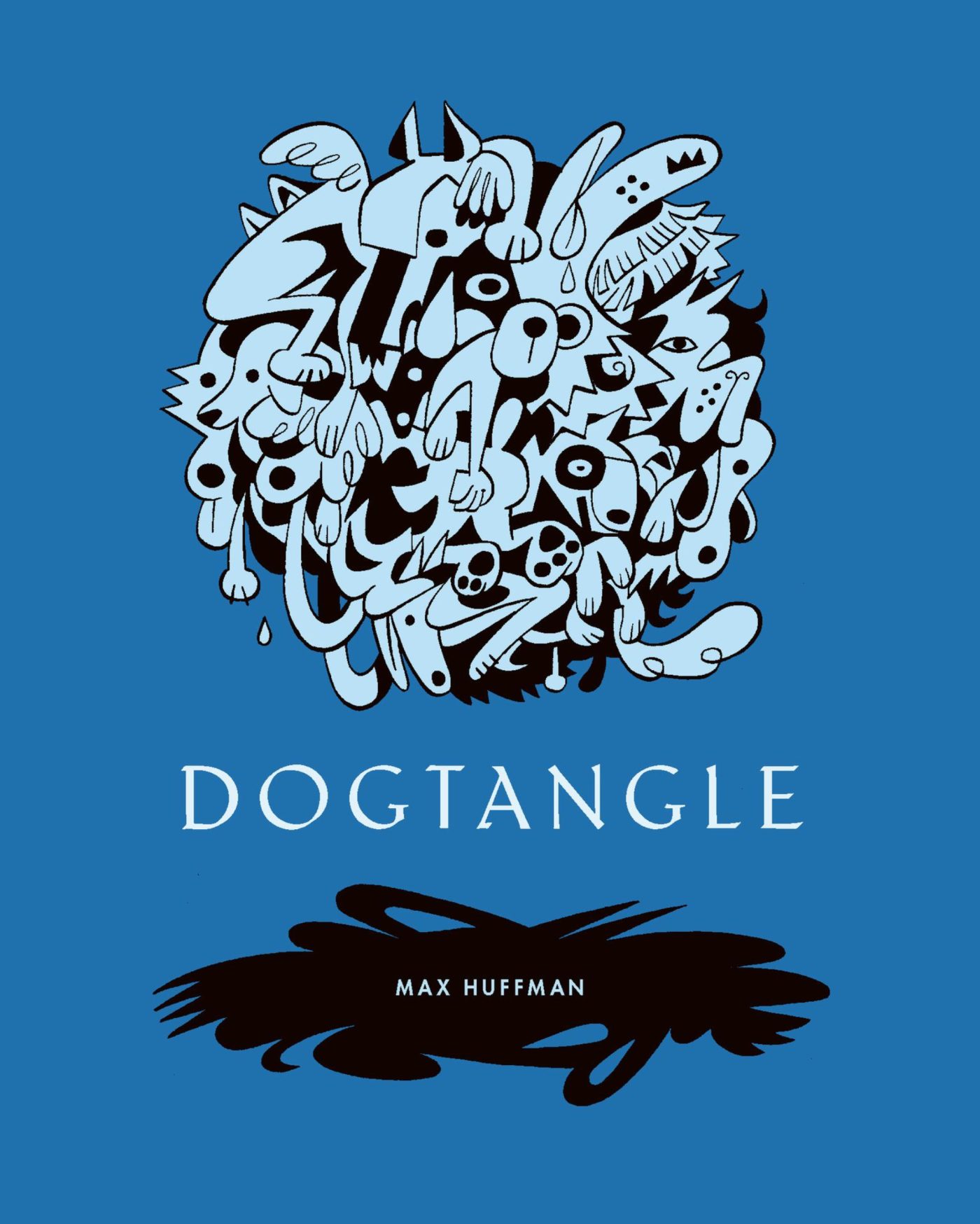

Land of Mirrors, Maria Medem- Dogtangle, Max Huffman

- Tales of Paranoia, R. Crumb

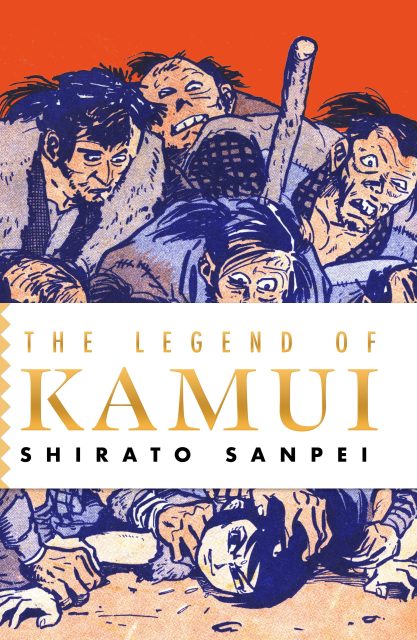

- The Legend of Kamui, Shirato Sanpei

- Laab Magazine No. 3, ed. Ron Wimberley

- Toxic Crusaders, Matt Bors and Tristan Wright

- Fever Dreams, Dakota McFadzean

- Stardust The Super Wizard Anthology, ed. Van Jensen various

- Total THB vol 1, Paul Pope

- Our Soot Stained Heart, Joni Hägg and Stipan Morian

- War, Garth Ennis and Becky Cloonan

- Mansect, Shinichi Koga

- Ordained, Robert Venditti and Trevor Hairsine

- Superman The Kryptonite Spectrum, W. Maxwell Prince and Martin Morazzo

- Moan, Junji Ito

- Fela Music is the Weapon, Jibola Fagbamiye and Conor McCreery

- Cannon, Lee Lai

- Planet Death, Derek Kolstad, Robert Venditti and Tomás Giorello

***

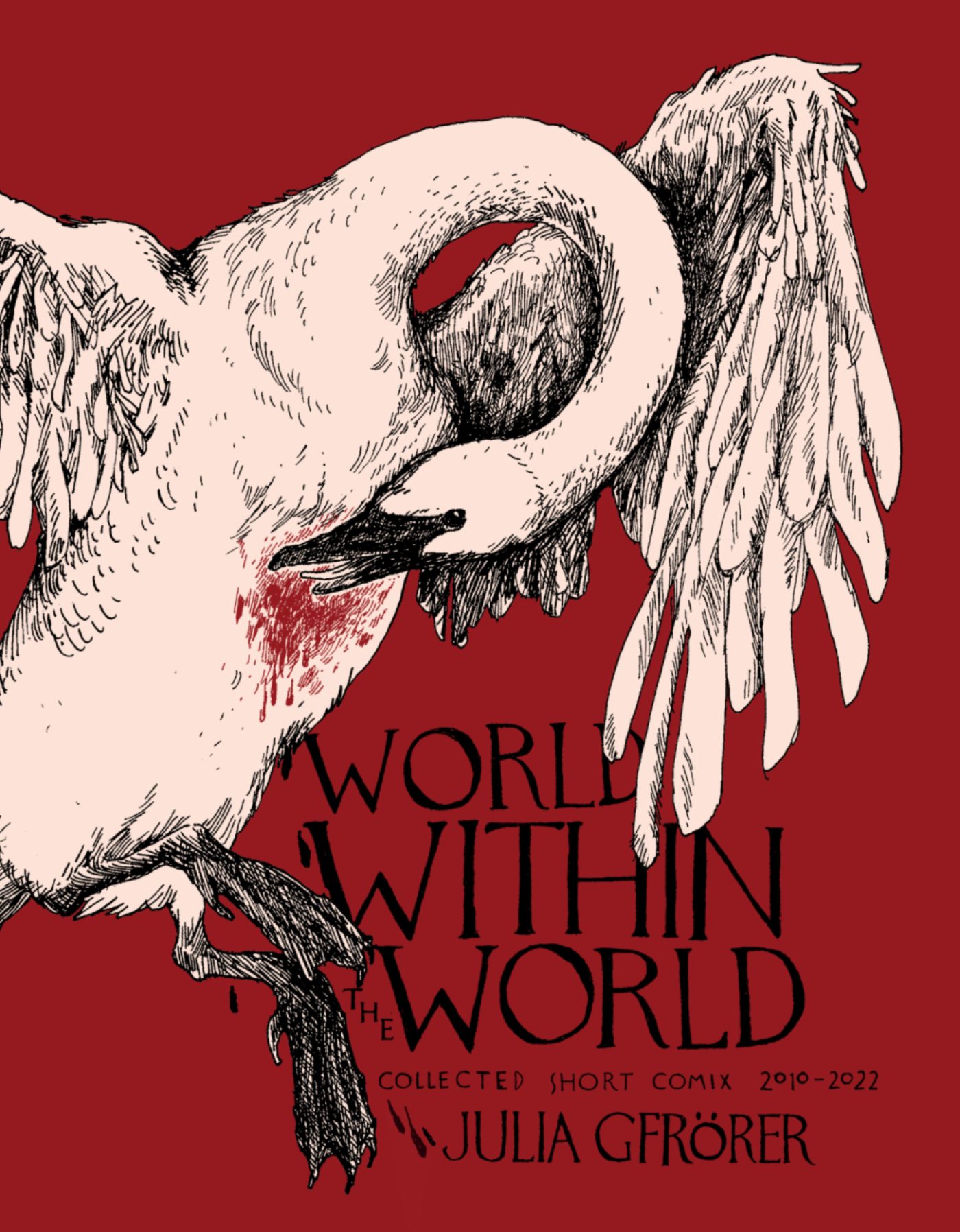

World Within the World: Collected Minicomix and Short Works 2010-2022 by Julia Gfrörer (Fantagraphics, 2025)

World Within the World: Collected Minicomix and Short Works 2010-2022 by Julia Gfrörer (Fantagraphics, 2025)Robert Aman

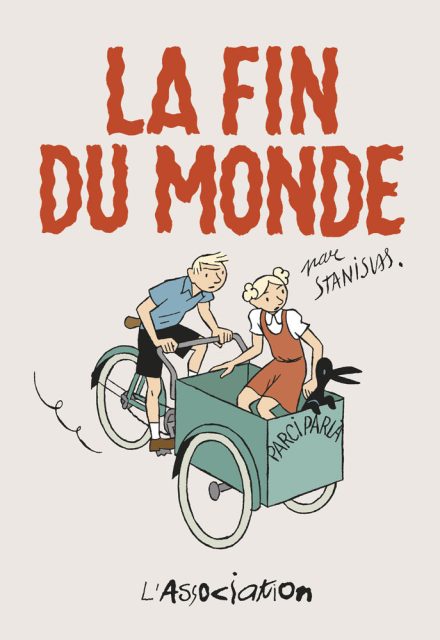

Although I firmly believe that the best comics are being produced right now — works that will only be surpassed by those yet to come— I can’t help feeling, when asked to sum up the year, that noticeably fewer comics have seen the light of day compared with last year. This impression is entirely subjective; I have no empirical data to support it. Still, it may not be wholly unreasonable given the dark clouds gathering over the comics landscape: rising tariffs, increasing production costs, Diamond’s bankruptcy, to name just a few possible factors. And if that weren’t enough, several publishers have reported serious financial losses, among them France’s L’Association, which has publicly appealed to its readers for support in order to survive.

That said, the year has also delivered a number of truly outstanding works, which I have done my best to rank in the list below.

An undisputed number one is Swiss cartoonist Nando von Arb’s Bouquet de peurs. This brick of an autobiographical work, dealing with von Arb’s mental illness, manages to fuse influences from Frida Kahlo, Brecht Evens, and illustrations reminiscent of Czech children’s books from the 1970s in a wholly unique way. Although mental illness is far from a new subject in comics, Bouquet de peurs is the most compelling work on the topic since David B.’s portrayal of his brother’s epilepsy from the 1990s.

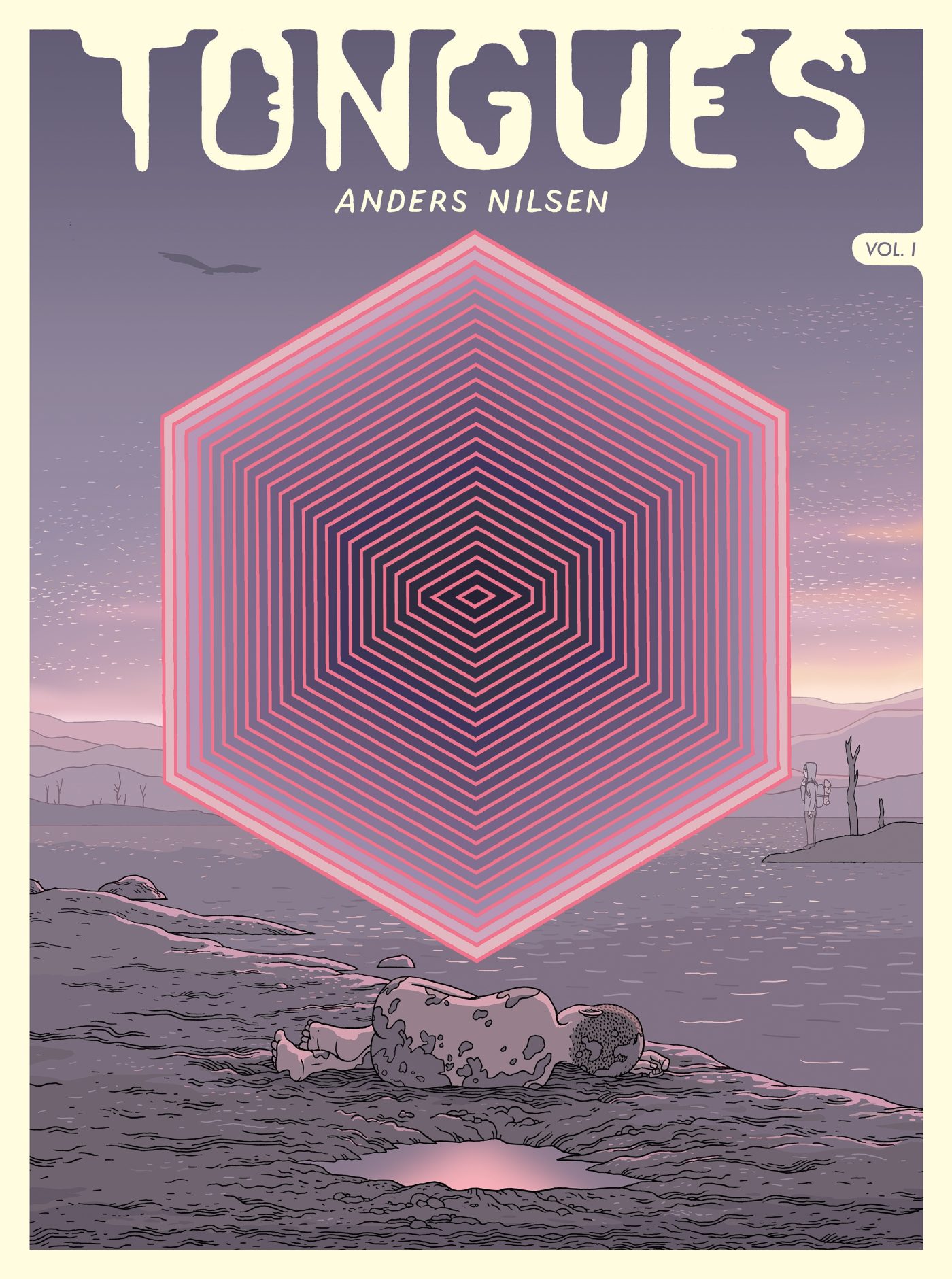

Anders Nilsen’s Tongues may contain one plot element too many, but few cartoonists can juggle Greek mythology, a talking chicken, soldiers, an American hitchhiker, and more with the same finesse as Nilsen. The result is a stunning reading experience, driven by powerful and often haunting imagery.

Moa Romanova’s second book in English, Buff Soul, can be read as a graphic travel diary, drawing on a long tradition of documenting life on tour. Romanova follows her friend ShitKid to a music festival in Texas, and while the book includes genre-typical elements — such as the rebellious and often self-destructive tendencies of the rock music scene — its greatest strength lies in its sensitive portrayal of genuine friendship.

When Jean-Christophe Menu, together with Étienne Robial, decided to revive the legendary 30/40 series, Menu was the first to contribute a volume of his own. Expectations were high, and he had no trouble living up to them. The comics dealing with his parents’ deaths rank among the finest work he has ever produced — and, by extension, among the strongest examples of autobiographical comics as a genre.

World Within the World, Julie Gfrörer’s collection of short stories revisits her familiar uncanny version of our world, one filled with desire, despair, and the universal need for connection. For all their macabre qualities, the dark corners Gfrörer explores are also very funny.

In sixth place, I’ve put Ville Ranta, who seems incapable of making a bad book. For over twenty years, Ranta has chronicled his life in comics. His latest work revisits the period when he was active at a Finnish cultural magazine, where he, among other things, published a comic that satirically commented on the Finnish political leadership’s response to the Muhammad cartoons controversy in Denmark—a topic he discussed in an interview with The Comics Journal. In Les buveurs de vin, the reader follows both the events themselves and their aftermath, interspersed with prodigious amounts of drinking. That Ranta remains untranslated into English becomes more baffling with every new book.

New York Review Comics deserves special praise for finally translating into English another book by Yvan Alagbé, co-founder of Amok and one of the most influential publishers of the French alternative comics scene of the 1990s. The book continues Alagbé’s sustained exploration of race and colonialism in contemporary France.

A younger — but equally prodigious — storyteller is Cameron Arthur, whose fanzine Swag has been a joy to follow. Stories from its early issues have now been collected into a single volume. With cartoonists like Arthur, the future of comics looks bright.

- Bouquet de peurs by Nando von Arb (Misma éditions)

- Tongues by Anders Nilsen (Pantheon)

- Buff Soul by Moa Romanova (Fantagraphics)

- Menu 30/40 by Jean-Christophe Menu (L’Apocalypse)

- World Within the World by Julia Gfrörer (Fantagraphics)

- Les buveurs de vin by Ville Ranta (Éditions ça et là)

- Misery of Love by Yvan Alagbé (New York Review Comics)

- Hidden Islands by Cameron Arthur (Bubbles)

- Baby Blue by Bim Eriksson (Fantagraphics)

- Cannon by Lee Lai (Drawn & Quarterly)

***

Tiffany Babb

While The Deviant (James Tynion IV, Joshua Hixson, and Hassan Otsmane-Elhaou) is very much a "Christmas serial killer story," it is also about how we can't always control aspects of our own identities, whether that stems from how society labels outsiders as "deviants" or how those labels affect how we see ourselves. This twelve-ssue series is able to balance a tense slasher story with thoughtfulness with a deeply personal touch.

***

Jason Bergman

The vast majority of my comics reading in 2025 was research for interviews on this site. Of those, I have to mention Anders Nilsen's Tongues, and the truly surprising return of Jeff Nicholson's Colonia as particularly noteworthy new books. Otherwise most of the new comics I read this year were ... fine, I guess? Not a whole lot came to mind when I sat down to look back on the year. We did get a new Love & Rockets collection from Jaime Hernandez (Life Drawing), which was excellent as always, and I also very much enjoyed Santos Sisters vol. 1 by Greg & Fake. But a lot of other books were just forgettable, if not downright disappointing.

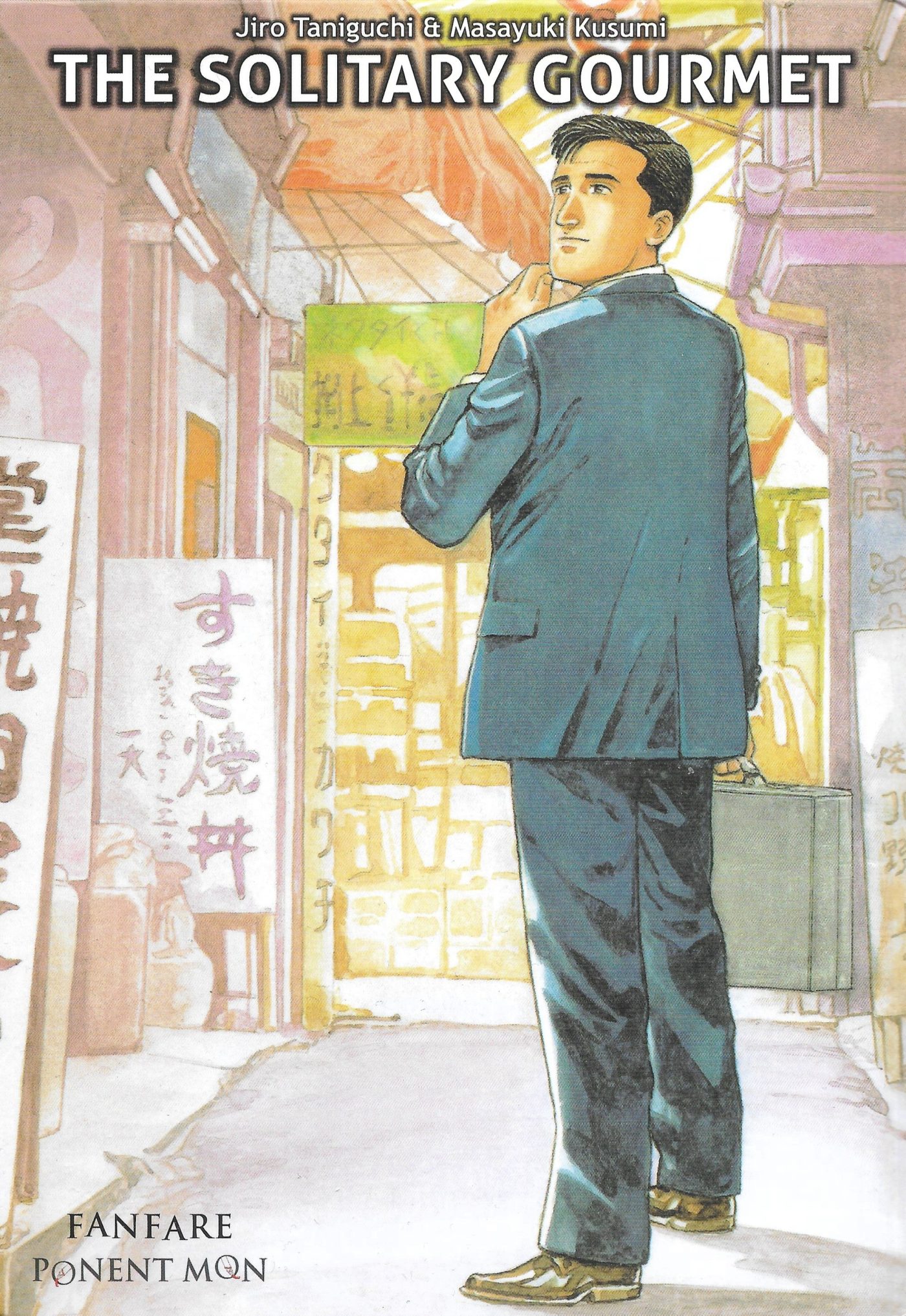

With one surprising exception, The Solitary Gourmet. There's a local Japanese restaurant my family eats at regularly, and they always play the television series based on this manga on their screens. Without subtitles, of course, forcing us to try to guess what's going on. I had dubbed the series "Inspector Food" because it looked like a show about a detective, only one where all he does is eat. I wasn't too far off, I suppose — he's not a cop, just a salesman. But anyway, the manga by Jirō Taniguchi and Masayuki Kusumi is wonderful. As noted by Joe McCulloch in his review, the book is best enjoyed in small bites, something I appreciate. It's small, it's quiet, there's no major drama to be found, it's beautifully illustrated, and it's all about food. Maybe I'm having flashbacks to all the time I spent wandering Tokyo by myself, or maybe it says something about my state of mind, but this weird book about a man eating food by himself is my favorite graphic novel of 2025.

***

Colin Blanchette

1) Hidden Islands by Cameron Arthur (Bubbles Zine Publications)

I passed up the opportunity to buy this book a few times before I pulled the trigger, and even then, I only bought it because of the high quality of Bubble’s other publications (Stories from Zoo by Anand was a revelation), not because the book looked that interesting at first glance. I was wrong. It’s a fantastic book of short stories, and it’s the book that I’ve thought about the most since I first read it. I hope that we see a lot more work from Cameron Arthur.

2) Tales of Paranoia by R. Crumb (Fantagraphics)

I was shocked when I heard that Crumb had a new comic book coming, hot on the heels of Dan Nadel’s wonderful biography. It was a pleasant shock, even though I was prepared for it to be forgettable work by a once great artist. Luckily for me (and everyone else, except his haters), he’s still a great artist, and he can still draw like a motherfucker. Even though he’s wrong about almost everything, Crumb communicates his beliefs clearly and effectively. This comic is by far the best value of the year as well. It’s a dense, satisfying read, and it’s re-readable as well. It delivers more than most graphic novels with ten times the page count.

3) Tongues Volume 1 by Anders Nilsen (Pantheon)

If you’ve been reading Tongues in its serialized form, then you’re probably aware that it’s a very good comic, but reading the existing story in one go is a different matter entirely. There’s still another big book coming to finish this story off, but I think it’s safe to say at this point that it’s Nilsen’s best book so far. Considering the fact that his previous work has ranged from good to excellent, that’s no mean feat. This book is the summation of his work as a cartoonist, and it’s thrilling to witness a great cartoonist at the peak of his powers dive headlong into his own preoccupations in such a considered and mature way.

4) Cornelius: The Merry Life of a Wretched Dog by Marc Torices (Drawn & Quarterly)

I knew nothing about this book or its creator before I read it. I flipped through it and looked good. When you take the time to actually look at it, though, you realize just how good it looks. The sheer craft on display is mesmerizing. Torices utilizes every kind of form and mode that he can think of to tell the story of a hapless loser meandering through his pathetic life who fails to aid one of the few people that’s ever been kind to him. The story is simple and it’s not as funny as it thinks it is, but I’ll admit I was impressed by the audacity of the storytelling, and the book overall.

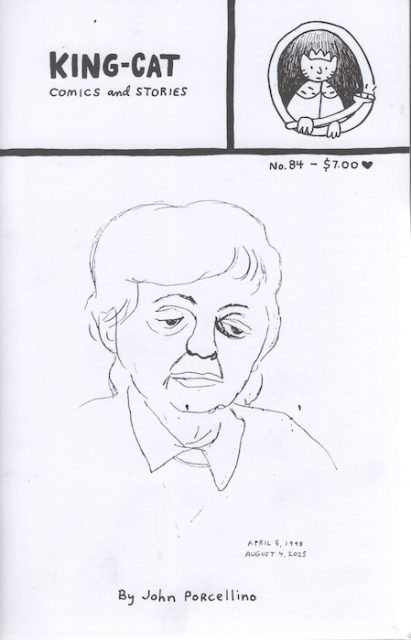

5) King-Cat Comics and Stories #84 by John Porcellino (self-published)

5) King-Cat Comics and Stories #84 by John Porcellino (self-published)

At this point, King-Cat is like the tides. It’s a natural force that seems inevitable, and you know the form will be familiar. The content is never the same, even if the preoccupations are. Love, death, music, groundhog sightings … they’re all here, as usual. At this point, Porcellino is an institution, of a kind; and like a lot of institutions, he’s taken for granted. He shouldn’t be. I’m grateful for each new issue of King-Cat and I hope he makes them for years to come.

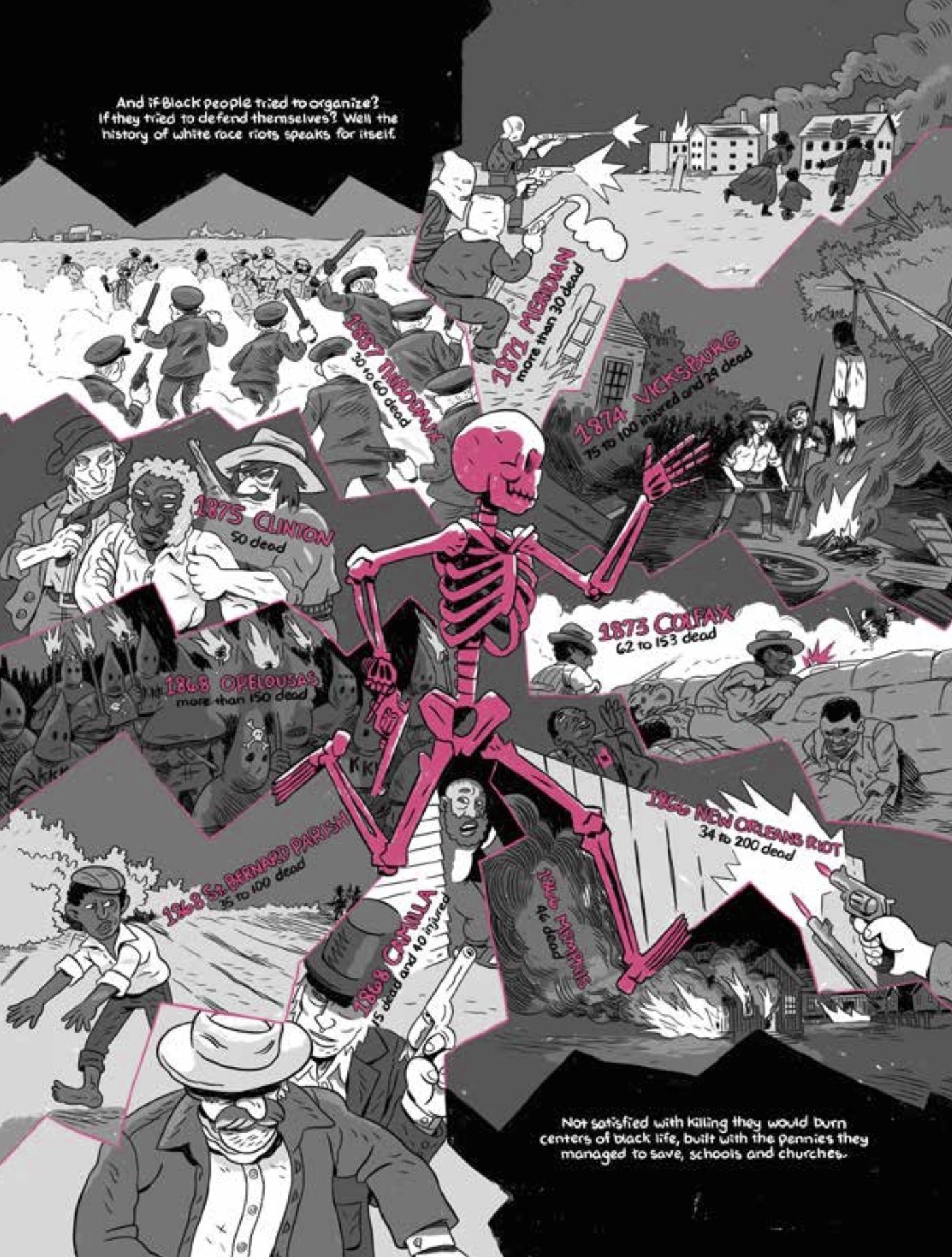

6) The Once and Future Riot by Joe Sacco (Metropolitan Books)

Measured against Joe Sacco’s other books, this is a fairly minor work. Of course, a minor work by Sacco is better than most cartoonists could ever hope for. India is vast, both in terms of its geography and its history, and this relatively thin book only scraped the surface of the corruption, sectarianism, and bloodletting that has plagued the country’s modern history. The book is beautifully drawn and Sacco packs a lot into these pages, but for the first time when reading one of his books I felt like maybe he had bitten off more than he could chew. As always, I’m glad he took the bite, especially since no one else seems likely to follow in his footsteps and make harrowing books like he has, over and over again.

7) Love Languages by James Albon (Top Shelf Productions)

Each of Albon’s books is different from the last. I’ve liked all of them. This book walked a tightrope, though instead of falling into the abyss, the danger was that it would fall into cloying sentimentality. That’s not a fate worse than death, mind you, but when the story is a romance that risk is high to begin with. The romance in this story is well-earned, even if it isn’t revelatory. Albon’s storytelling is, however. I’ve never seen a comic handle multiple spoken languages as skillfully as he does here, blending English, French, and Mandarin together, artfully. It’s a beautiful comic by an underrated cartoonist.

8) The Ephemerata: Shaping the Exquisite Nature of Grief by Carol Tyler (Fantagraphics)

I don’t know what I expected this book to be, but it was different than whatever I expected. I knew that the drawing would be great, and it is. There are times when you come across a page that’s so unbelievably gorgeous it just stops you in your tracks. Tyler’s exploration of her grief, and grief in general, gets exhausting after a while, but I think that’s the point. Over the course of 200+ dense, lushly illustrated pages she digs into one of the hardest experiences life has to offer, and from that pain she creates beauty. It’s a book that will sit with you.

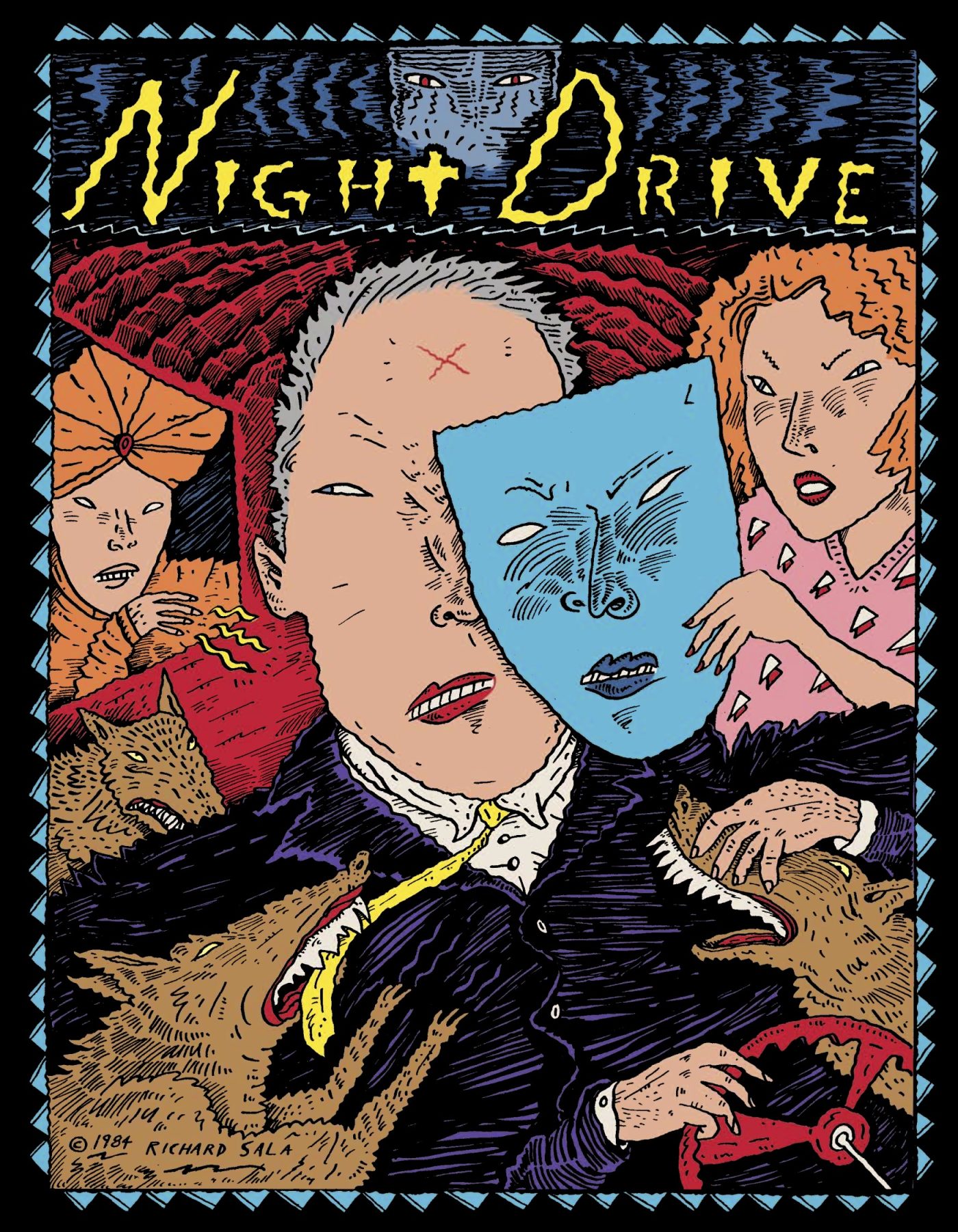

9) Night Drive by Richard Sala (Fantagraphics)

Richard Sala has been one of my favorite cartoonists for a very, very long time. This book, originally printed in a magazine format forty years ago, has eluded me, so imagine my surprise, and pleasure, when I heard that it was being printed in a luxurious hardcover edition. This early work is a lot of fun. All of Sala’s work was fun, though the way it was fun varied greatly over the years. For anyone who fondly remembers his Invisible Hands segments from MTV’s Liquid Television, I would imagine they would enjoy this work. For me, it was the missing piece of a puzzle I’ve been putting together for a few decades and, happily, a wonderful comic from beloved cartoonist.

10) Ginseng Roots: A Memoir by Craig Thompson (Pantheon)

What this book is, is impressive. Making a book this long is impressive (440+ pages) but it’s not uncommon nowadays. What is uncommon is how much cartooning went into every single page. Thompson lavishes those pages with a lot of ink, and a lot of stories, too. It’s subtitled “A Memoir” and it is one, but it also delves into the history of his family, his community, ginseng farming (in China and North America), and where they all are at today. The ambition of this book impressed me, and it delivered on that ambition.

***

Kevin Brown

Absolute Batman Vol. 1: The Zoo by Scott Snyder, Nick Dragotta, and Frank Martin

DC’s Absolute series reimagines well-known heroes without their well-known back stories. This Bruce Wayne grows up lower- to middle-class, so he lacks the financial resources of the traditional story, leaving him to rely even more on his mental abilities. Gotham is the same place, though, overrun by crime bosses and a group called the Party Animals who seek to sow chaos. The strongest part of this work is that the focus remains solely on Batman’s desire to do good in the world, to seek justice for everybody, which has always been at his core.

You Must Take Part in Revolution by Badiucao and Melissa Chan

Badiucao and Chan don’t provide a neat ending to their work, as there aren’t easy answers for how and when one should act against a tyrannical government. However, they’re clear that inaction isn’t a viable option.

Spent by Alison Bechdel

It seems obvious to mention Alison Bechdel when talking about great work from the year, but she’s taken a bit of a risk here by returning to fiction after her past three memoirs. While she certainly focuses on friends and community, as she did in Dykes to Watch Out For, her exploration of how we spend our time or money or energy seems particularly relevant today. She even ends with a brief glimmer of hope in community, something we could certainly use right now.

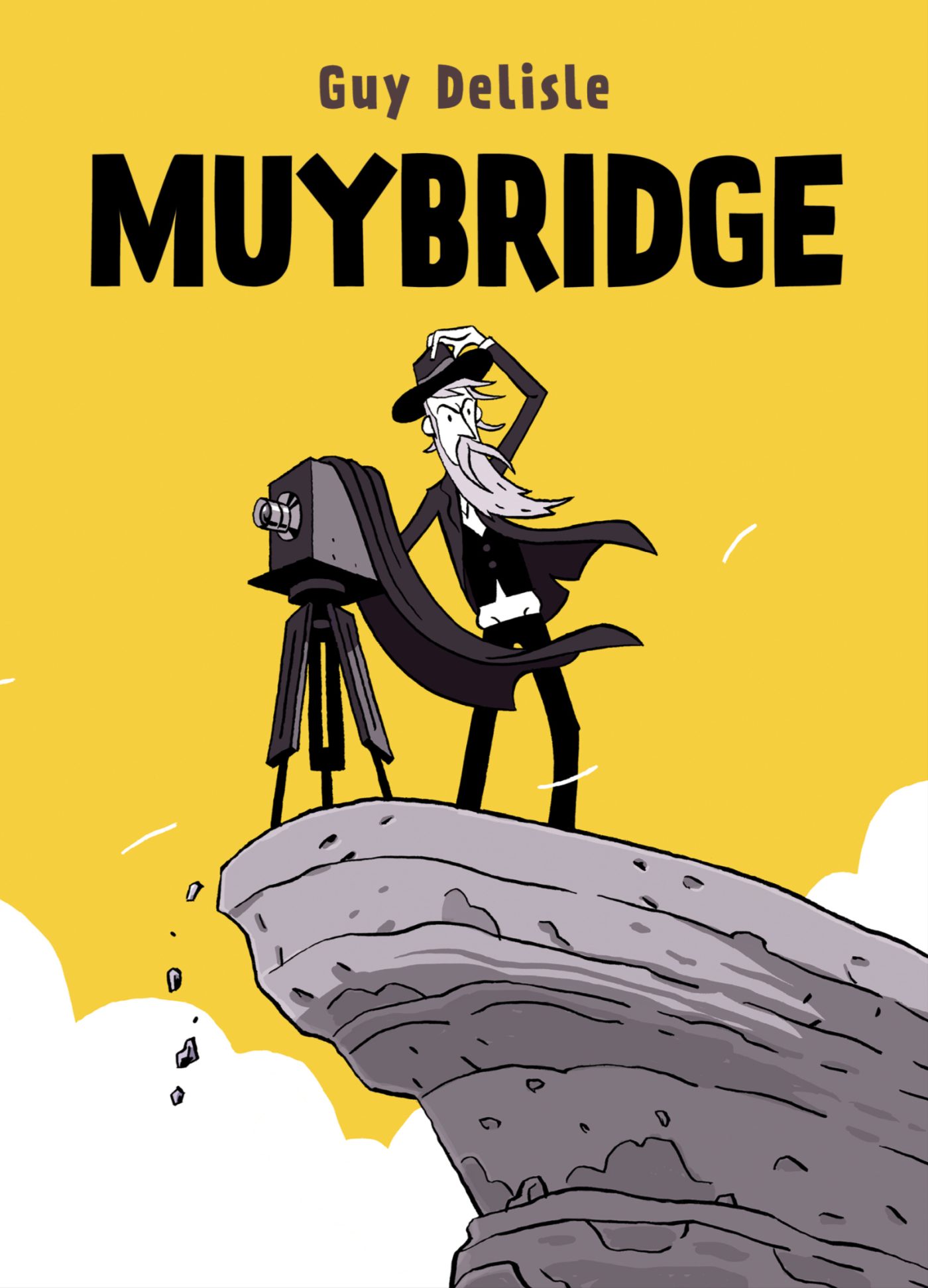

Muybridge by Guy Delisle

Delisle goes well beyond Muybridge’s famous photograph of a horse to create the world of invention that he was a part of. Most interestingly, Delisle shows Muybridge’s influence on animation, motion pictures, and graphic works like Delisle’s, an influence that continues well beyond what Muybridge could imagine.

Absolute Wonder Woman, vol. 1: The Last Amazon by Kelly Thompson, Hayden Sherman, Mattia de Iulis, and Dustin Nguyen

Here, Diana doesn’t grow up on Themyscira. Instead, she’s raised in the underworld. Rather than preventing her from caring about and fighting for humanity, that banishment simply gave her more weapons to fight for justice.

Nightwing: On with the Show by Dan Watters, Dexter Soy, Veronica Gandini, and Wes Abbott

Dan Watters and team take on the challenge of picking up Nightwing’s story after the amazing run led by Tom Taylor. They draw on Nightwing’s past experiences with the circus and his early days with Batman, while throwing him in the middle of a gang war that has begun after Blockbuster’s death in the earlier series.

***

Clark Burscough

Well, I don’t know about you, but 2025 sure had a lot of “Lemon, it’s Wednesday” vibes to it for me, so, much like last year, a list compiled in a bedraggled state, running to the lecture hall with a slice of toast in my mouth, but a list nonetheless, from your friendly neighbourhood linkblogger.

While the lion’s share of the pop culture outlet coverage seemed to go to the title with the steroidally embiggened versions of Gotham’s denizens, for this regular-sized reader the most interesting of DC Comics’ Absolute line have absolutely been Absolute Wonder Woman by Kelly Thompson, Hayden Sherman, et al. and Absolute Martian Manhunter by Deniz Camp, Javier Rodriguez, et al., the first volumes for both of which mess with their respective mythoi in interestingly spiky ways, and don’t mind assuming that the reader will be able to keep pace and catch up when dropped in media res, and both of which also have some of the most pleasingly arresting visuals I’ve seen in a superhero comic for a while. Now, as long as they don’t tank the ongoing supracontinuity fun with plodding crossover events that kill an entire line’s momentum, we’ll be laughing.

While the lion’s share of the pop culture outlet coverage seemed to go to the title with the steroidally embiggened versions of Gotham’s denizens, for this regular-sized reader the most interesting of DC Comics’ Absolute line have absolutely been Absolute Wonder Woman by Kelly Thompson, Hayden Sherman, et al. and Absolute Martian Manhunter by Deniz Camp, Javier Rodriguez, et al., the first volumes for both of which mess with their respective mythoi in interestingly spiky ways, and don’t mind assuming that the reader will be able to keep pace and catch up when dropped in media res, and both of which also have some of the most pleasingly arresting visuals I’ve seen in a superhero comic for a while. Now, as long as they don’t tank the ongoing supracontinuity fun with plodding crossover events that kill an entire line’s momentum, we’ll be laughing.

Taking the coveted top spot for comic that made me say “oh, mate, brutal” out loud the most times while reading it this year, we have The Sickness, Volume 1 by Lonnie Nadler, Jenna Cha, et al., the timeline hopping nastiness of which put me in mind of the creeping descent into madness and unmooring from reality as depicted in Providence by Alan Moore and Jacen Burrows. The slow burn reveals and peeling back of the consistently unnerving story playing out in the first collected volume for the series has left me strongly anticipating that volume two will also be a future best-of contender.

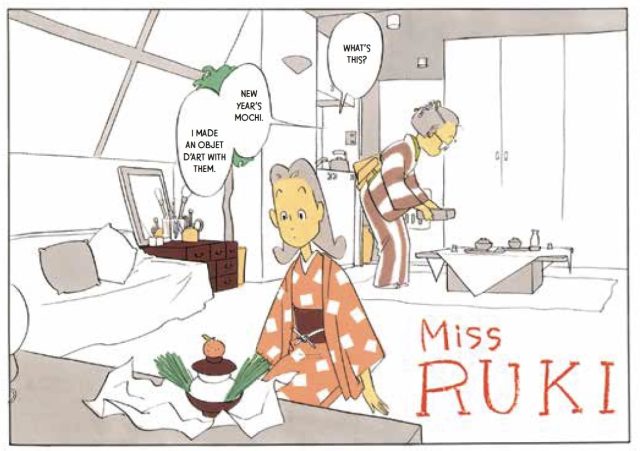

Cleansing the palate after the nastiness [complimentary] of the last pick, comes the warmhearted delights of Miss Ruki by Fumiko Takano, translated by Alexa Frank, which was yet another annual pick cribbed from Sally Madden and Katie Skelly’s aces Thick Lines podcast, and which was a much needed dose of a slice-of-life strip that’s just consistently Really Nice and Properly Funny. The closing narrative coda, returning to best friend protagonists Miss Ruki and Ecchan ten years down the line, is genuinely lovely.

As a classic dyed-in-the-wool trade-waiter, I was very glad to see The Santos Sisters by Greg & Fake receive a winningly handsome collected edition (peep that see-thru acetate dust jacket and thick paper stock) this year, which serves well the nod and a wink punchlines to dirty jokes with clean lines to be found within. This book sings as this year’s shining example that, sometimes, like Dandadan in last year's list, all you really need, to pep you up during a grim period in history, is a comic that’s horny and weird and fun and good to look at in equal measure.

***

Thomas Campbell

Alive Outside, ed. by Cullen Beckhorn and Marc Bell (Neoglyphic Media). Featuring: Aapo Rapi, Aaron Rossner, Andy Cahill, Angela Fanche, Becchi Ayumi, Bridget Trout, Christian Schumann, Clayton Schiff, Dongery, Doug Allen, Dylan Jones, Eden Veaudry, J Bradley Johnson, Jonathan Peterson, Jordan Rae, Joe Grillo, Joey Haley, Julie Doucet, Julien Ceccaldi, Kari Cholnoky, Keith Jones, Leomi Sadler, Lilli Carre, Lukas Weidinger, Marc Bell, Mark Connery, Matt Lock, Poncili Creation, Roman Muradov, Ron Rege Jr., Shoboshobo, Steven M. Johnson, Susan Te Kahurangi King, Theo Ellsworth, Trenton Doyle Hancock

Beautiful Monster by Maruo Suehiro (Bubbles)

Bernadette #2 ed. by Angela Fanche and Katie Lane (Self-published). Featuring Pia Drummond, Eero Talo, Mackenzie Morse, Lydia Mamalis, Allee Errico, Clair Gunther, Ellen Addison, Bella Carlos, Dakota Knicks, Tana Oshima, Katie Lane, Minnie Slocum, Leslie Weibeler, Molly Herro, Gina Wynbrandt, Fidelia Schlegl, Owwi Lee, Em Frank, Ash Fritzsche, Nora Fulton, Phoebe Mol, Pris Genet, Susan Kaplan, Angela Fanche, Waja Shchipko, Pamela Anderson, Jenny Zervakis, Alina Jacobs, Maggie Umber, June Gutman, Alex McGrath, Mariagiulia Pedrotti, Shuai Yang, E.A. Bethea, Bri Al-Bahish, Mara Ramirez (Self-published)

Butterface by Matt Seneca (Self-published)

Dogtangle by Max Huffman (Fantagraphics)

The Emphermata by Carol Tyler (Fantagraphics)

Record 1-4 by Jason Overby (Self-published)

Revenge #2 by Samandal Comics Collective (Lebanon) (Published in the US Beehive Books). Featuring: Rami Tannous, Lena Merhej, Karen Keyrouz, Carla Aouad, Joseph Kai, Nour Hifaoui, Raphaelle Macaron and Shakeeb Abu Hamdan

Valley Valley/ Idella Dell by Audra Stang (Frog Farm)

World Within A World by Julia Gfrörer (Fantagraphics)

***

From River Rangers #8.

From River Rangers #8.RJ Casey

As I get older, I become more and more appreciative of cartoonists who give themselves up completely to the page — and the reader — and continue to push the medium in fascinating directions. Thank you to all the artists listed below. (If I have written about any of these books in my “Arrivals and Departures” column this year, I will include a link.)

Honorable Mentions (in no order):

Milk White Steed by Michael D. Kennedy

Tedward by Josh Pettinger

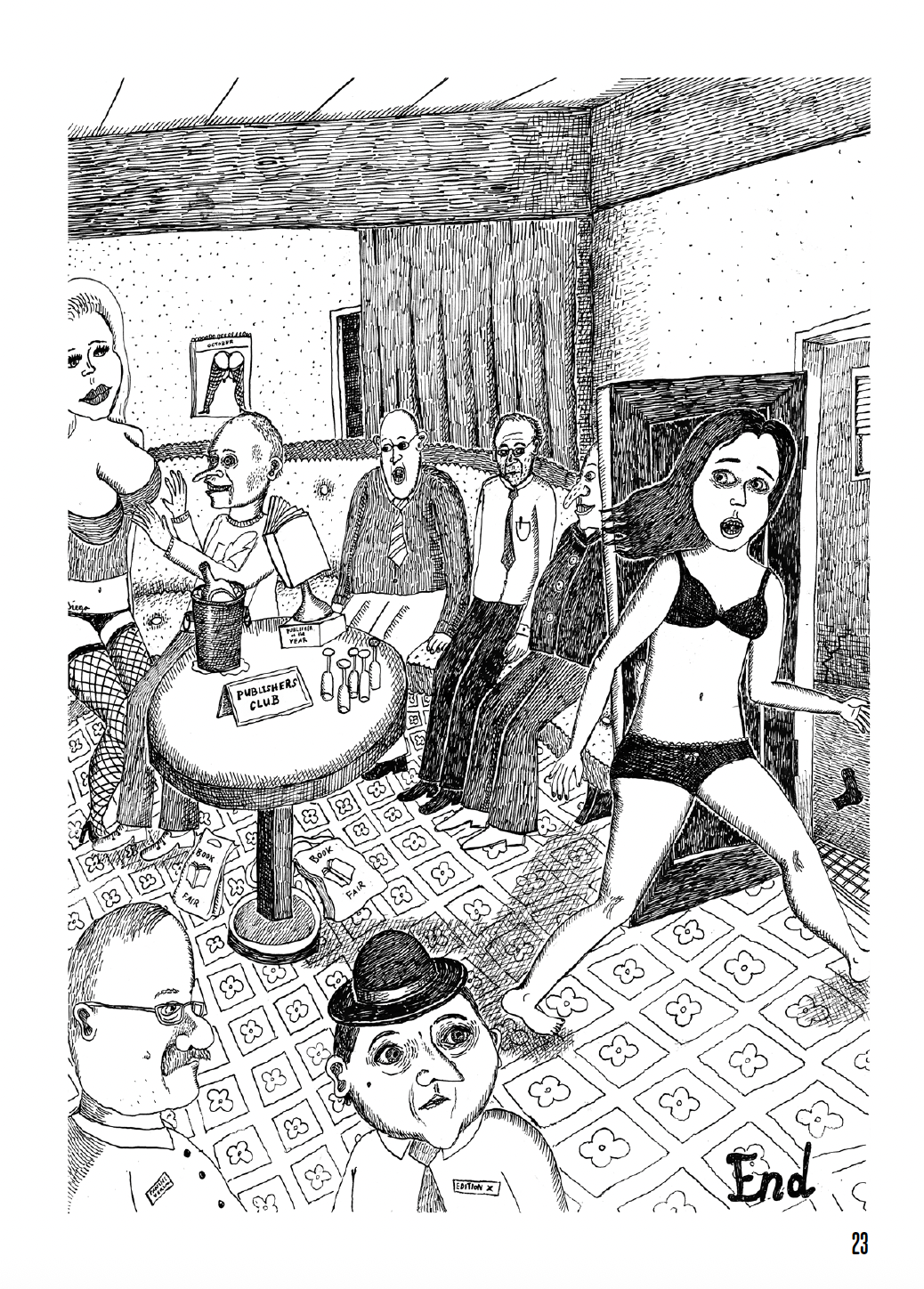

Prop Comic by Veronica Graham

Animal Denial by Emilie Gleason

K is in Trouble Again by Gary Clement

Them Shaped Clouds by Max Huffman

The Shifting Ground Vol. 1 by Joe Walsh

Laser Eye Surgery by Walker Tate

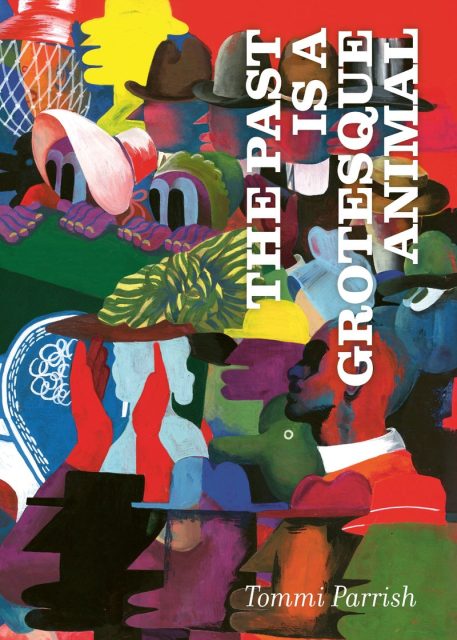

The Past is a Grotesque Animal by Tommi Parrish

Slick Susan and the Mysterious Soup by Rebecca Kirby

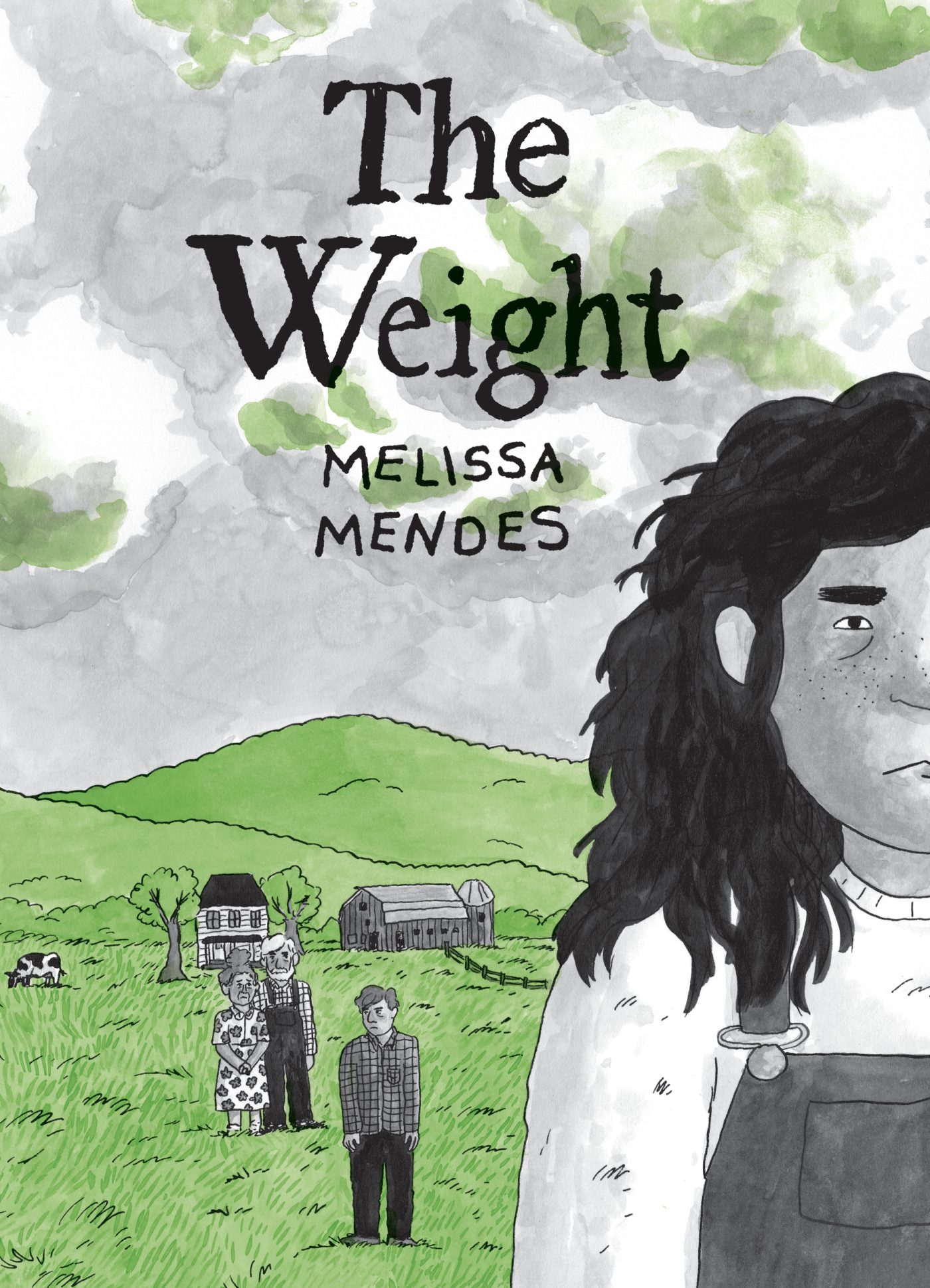

The Weight by Melissa Mendes

“Kristof” by Alex Schubert

Igor the Assistant by Haus of Decline

Top 10 of 2025 (in order!):

10.) Allee Errico’s pages in Bernadette #2

9.) Pleasure Beach #1 by Josh Pettinger

8.) Terminal Exposure by Michael McMillan

7.) Flea by Mara Ramirez

6.) Christine by Cyril Vilks

5.) Valley Valley/Idella Dell by Audra Stang

4.) Precious Rubbish by Kayla E.

3.) Big Gamble Rainbow Highway by Connie Myers

2.) Dogtangle by Max Huffman

1.) River Rangers #8 by Henry McCausland

***

Henry Chamberlain

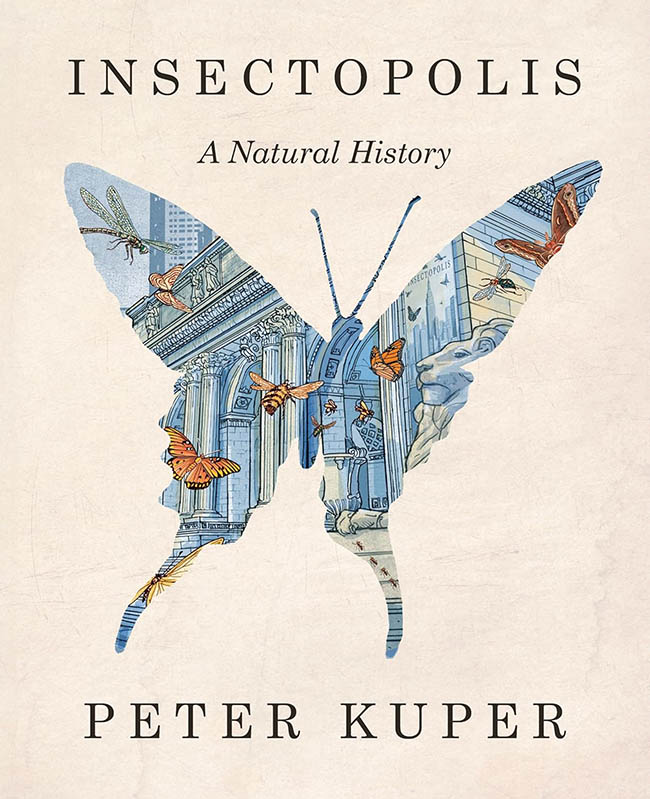

We began 2025 with a big event title, the first volume of Tongues, by Anders Nilsen, and we end the year with another career milestone, Ephemerata by Carol Tyler. Both books are equally captivating in their own ways and speak to the care and dedication of their respective creators. Both books are multi-layered, push the limits of the medium and maintain the traditional structures in beautiful ways. Other titles in 2025 doing the same at an exemplary level are Insectopolis by Peter Kuper, the collected Gingseng Roots by Craig Thompson, The Once and Future Riot by Joe Sacco, Milk White Steed by Michael D. Kennedy, Photographic Memory by Bill Griffith and The New York Trilogy, featuring Paul Karasik as editor and contributor.

There’s always more to add to a list and it depends upon the focus, among other things. Perhaps it can be dependent upon a cool factor—but we can’t all be cool kids, right? A list of what gets excluded is as intriguing as what gets included. Anyway, I suppose you can honestly get tripped up in terms of what best represents any given year. One thing to keep in mind is that any art form, particularly comics, is years in the making and various versions of it might come out at various years until you get the definitive version. You also have the heavy hitters, the giants in the industry, right alongside newcomers. If you think it’s easy for me and my friend and colleague Paul Buhle to sift through the onslaught on titles each year and review them at Comics Grinder, then you’ve got a screw loose. At the end of the day, it’s those big-name comics artists, out there leading the way, who are hopefully keeping us all honest. They’re there to set an example and are supposed to tell us we’re all in this together. With that in mind, I add to this list, in no particular order, notable cartoonists making notable work:

Introverts Illustrated by Scott Finch, available thru Partners & Sons.

This Slavery by Scarlett & Sophie Rickard, published by SelfMadeHero

The Poet Volumes 1 & 2 by Todd Webb (self-published).

Molly and the Bear by Bob and Vicki Scott, published by Simon & Schuster.

Wally Mammoth: The Sled Race by Corey R. Tabor & Dalton Webb, published by HarperCollins.

Tedward by Josh Pettinger, published by Fantagraphics.

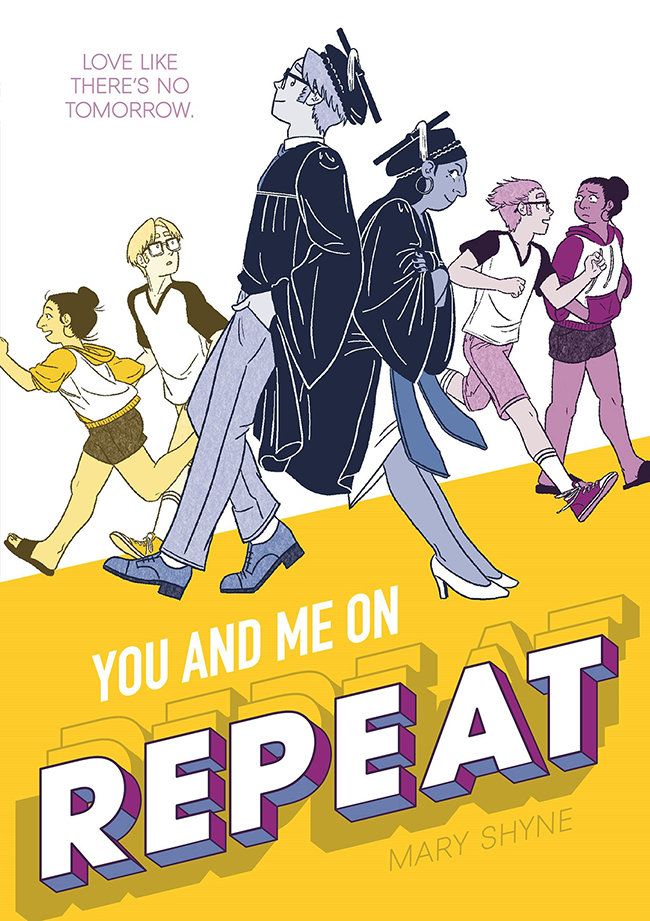

You and Me on Repeat by Mary Shyne, published by Henry Holt.

The Horrors of Being a Human by Desmond Reed, published by Microcosm Publishing.

Tuck Everlasting: The Graphic Novel by K. Woodman-Maynard, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

This Beautiful Ridiculous City by Kay Sohini, published by Ten Speed Press.

Raised by Ghosts by Briana Loewinsohn, published by Fantagraphics.

Tales of Paranoia by R. Crumb, published by Fantagraphics.

Raymond Chandler’s Trouble is My Business by Arvind Ethan David & Ilias Kyriazis, published by Pantheon.

The King’s Warrior by Huahua Zhu, published by Bulgilhan Press.

***

Helen Chazan

I hate writing best-of lists. Even with the caveat of “favorite” over “best,” I feel these lists are often a testament to what I have not read and what I have overlooked far more than what I love. Nonetheless, I persist with these damn things, because telling people what comics I love is something I was put on this earth to do. Perhaps this is weakness, but nothing has made me gladder as a critic than the kind words from readers and artists alike that I've gotten over the years. I'll go on. (lol)

2025 was a bad year for human rights but arguably a good year for comics. A great argument in favor of it being a good year for comics is that I published a few. An even better argument is that we got the collected Dogtangle this year. My favorite comics are formally ambitious, ranging from literary work to literal pornography, all tied together by a persistent excitement for the medium they live in. I've listed out a few:

Dogtangle by Max Huffman, Fantagraphics

2025 is the year of Dogtangle. Social satire that collapses in on itself. Cartoon humor that verges on formlessness. A love story, perhaps. A very big dog. I should have more words about Dogtangle, but how can I sum up this mass of mutts? It speaks for itself, or, perhaps, barks.

A Garden of Spheres Vol. 1 by Linnea Sterte, Peow2

A vast, beautiful, curious book that demands revisitation. Wide open vistas for the eyes to drink.

What Happened After My Place Got So Humid It Grew Magic Mushrooms and I Ate Them and Got Super Horny by Karasu Chan, J18

I am dead serious, one of my favorite comics this year was this ero-manga with that title. Visually inventive and deeply funny pornography about a woman's delusional quest to make a real friend, bolstered by energetic mark-making and impeccable comedic timing. Likely the comic I have recommended to people in conversation the most this year, tied with the majesterial Dogtangle (usually brought up in different company, mind you ... Usually.).

Unsinkable Ship of Fools by Jonas Goonface, Iron Circus

Remaining on the subject of pornography (and we must!), nobody draws people fucking right now quite like Jonas Goonface. Ship of Fools is a brilliant work of folklore-by-way-of-sex-farce full of color and weight that should embarrass all other action cartoonists of any variety. Deep erotica that you will return to.

Aneido's Anthology 1: The Soul-Selling Corporate Drone & Other Fanciful Tales by Aneido, Red String Translations

Recency bias may be speaking here (I just read this one), but after trudging through a fair bit of yuri this year, green or otherwise, Aneido is the artist whose work has captivated me the most overall and this collection is my favorite yet. Their line is soft and pleasant, their stories hang dreamlike in a space between wish fulfillment and something more otherworldly. A reminder that queer comics and alternative comics share the same urge at their root, to do something better than the mainstream.

Idella Dell and Valley Valley by Audra Stang, Self published

There are a lot of comics I read on social media this year and some of them were even very good. Audra Stang is doing something else, the freshest comics-on-comics thing to come along in a long time. Stang loves her characters, and beats them over and over with deeply familiar grief and rage. Both of these women suck and I am rooting for them.

Szarlotka by Jas Hice, Frog Farm

A small, fucked up story, one of the most beautiful two-tone riso print jobs I've seen in a long time, a novella of a zine that cements Hice as an artist to watch. I can't get enough of the Hichcockian vice of voyeur and victim in this one. Troubling!

SF “Shorts Folio” Serialized Fragments of Supplementary Files #1 by Ryan Cecil Smith, self-published

Speaking of amazing riso printing, this comic is probably my favorite book as an aesthetic object this year. These colors, wow! It's been a while since Smith's cast of adventurers last graced spinner racks, and they are truly a sight for sore eyes. You simply have to love a comic about a mailman in space.

Round World Thinking by Ana Woulfe, Reptile House

Another beautiful riso artifact, that stands beside Dogtangle as a gag comic that is a universe unto itself, a liberatory trans-femme project in the Gendertrash tradition that gets into the weeds with plants and isn't afriad to let out a cackle. More comics like this forever!

In brief, I will also mention a few of my favorite reprints and localizations of “classics” from this year:

- Legend of Kamui by Sanpei Shirato, Drawn and Quarterly

- Beautiful Monster by Suehiro Maruo, Bubbles

- My Name is Shingo by Kazuo Umezz, Viz Media

- Ashita No Joe: Fighting for Tomorrow by Tetsuya Chiba and Asao Takamori, Kodansha

- Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist by Dianne DiMassa, NYRC

More ink will be spilled on these by yours truly in due time.

To take a brief dip in the conflict of interest reservoir, most of my favorite zines this year were by the Hamilton-based cartoonist Zoot, who I have published in my anthology comic Afternoon Affair and who tabled next to my press at Expozine in Montreal. Bias disclosed, nobody is doing it like them. Highlights this year included the informative How To Get Bit By A Werewolf, the furry dyke drama Butch Bait (published by the gods at Diskette Press), and the truly miraculous BL boner pill crack ship The Hardest Day Of My Life. Read those if you get a chance, and you'll understand why I couldn't not mention them.

And on that questionable note, I bid you adieu. Hopefully 2026 is a better year for everyone, and a lot of comics are good as well.

***

Michael Dooley

It's my second annual “Not-E*sn*r Awards by a Former Will Eisner Awards Judge (2020)," where I'll again bypass the nomination process and declare category winners based on my own "Best of the Year" opinions. Any relation between other, official Awards and mine is purely comical.

Ice Cream Man #43: One-Page Horror Stories by W. Maxwell Prince, Martin Morazzo, Zoe Thorogood, Grant Morrison, Matt Fraction, Kelly Sue DeConnick, Geoff Johns, Matt Fraction, Patton Oswalt, Jeff Lemire, etc. (Image) ~ Best Single Issue/One-Shot

You needn’t be familiar with Ice Cream Man and co-creators Prince and Morazzo’s bold, ongoing structural experiments with the medium to enjoy the rich variety of flavors offered, here served in tasty, single-page scoops. Prince adroitly authors multiple stories and writers like Johns, Morrison, DeConnick, and Fraction bring their own unique, terrifying sensibilities, each rendered in styles to enhance the stories, wonderfully told through a variety of narratives and formats. Among the most imaginative are a Candy Land-ish board game, a Gustav Doré-styled descent into Hell, and, most frighteningly: a New York Times front page. Creepy. And yummy.

Monkey Meat: The Summer Batch by Juni Ba (Image) ~ Best Limited Series

With stylized art reminiscent of Michael T. Gilbert, Monkey Meat immerses you in its hilarious, energetic asphalt-and-jungle world. Inside the Monkey Meat Company, feces are flung at capitalism, gods, tourism, the military, colonization, and even piloted robots. To emphasize his themes, Ba makes full use of his medium with such devices as selective coloring and frequent, intense, in-your-hairy-face splash pages. These absurd, endearing, despicable anthropomorphs have you hoping for further installments.

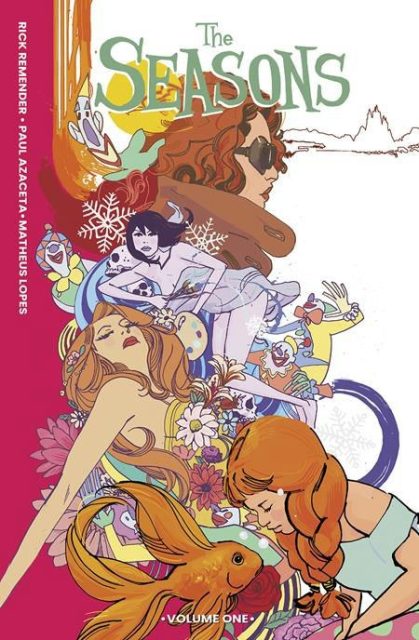

The Seasons, Volume 1 by Rick Remender and Paul Azaceta — Best New Series and Paul Azaceta, The Seasons #1-4 (Image) ~ Best Cover Artist

The Seasons, Volume 1 by Rick Remender and Paul Azaceta — Best New Series and Paul Azaceta, The Seasons #1-4 (Image) ~ Best Cover Artist

Seasons is a delightfully sinister adventure/horror/mystery, rendered in joyous, vibrant hues. Remender introduces us to the enchanting Season sisters, each bursting with their distinct personalities: Autumn, serious archaeologist; Summer, globe-trotting, temperamental superstar; Winter, passionate artist and mentor to the effervescent Spring, who kicks off a carnival adventure in a thrilling chase of… an envelope?

Artist/co-creator Azaceta treats us to bold visuals on every page, and each of his four covers has its distinctive appeal, such as a threatening skull-clown faux-collage and a bold graphic recalling Esteban Maroto and Bob Peak’s Camelot. When you’re in the mood for fun, scary adventure, Azaceta’s creative virtuosity bids you to welcome any time of the year.

Little Batman, Month One by Morgan Evans and Jon Mikel (Penguin/Random House) — Best Publication for Kids

In Little Batman, writer Evans offers smart and well-delineated answers to nagging questions such as “Why does Batman need to pose as Bruce Wayne?” from the point of view of Bruce’s son, Damian. The young Wayne wants Little Batman’s exciting life all the time — “Homework is a crime!” — but he also learns the importance of being himself. Mikel’s art, a delightful mix of Sergio Aragones and Kyle Baker, keeps things lively, with pastiches of Batman: Year One and Golden Age Batman. And his splendidly fun silent sections — drawn by “Damian” and dabbed with outside-the-lines “crayon”, courtesy of colorist Ian Herring — should inspire even the youngest future Bat-artist. This little Batman story is most enjoyable for big people as well.

Daisy Goes to the Moon by Mathew Klickstein and Rick Geary (Fantagraphics) ~ Best Publication for Teens

The history behind Daisy is a trip in itself. Briefly, the real Daisy Ashford (1881-1972) began amusing her family with stories beginning at age four. Eventually, J.M. Barrie (of Peter Pan renown) printed them complete with the misspellings and rambling logic of genuine childhood innocence. Here, Geary departs from his established panel format while still displaying his unmistakably endearing storytelling mastery to perfectly tell Daisy’s rocketing adventures. Young readers will delight in her lovable self-admiration, bravery, cleverness, and playful wordplay, as well as her lighthearted, endearing companions. Adults will appreciate the antiquarian science, as well as giggle at Daisy’s spirit and cheekiness. Read it together with the kids. You’ll love it to the moon and back.

Emma & Capucine, Volume 1 by Jérôme Hamon and Lena Sayaphoum (TokyoPop) ~ Best International Publication for Teens

In this elegant bande dessinée, the teenage Emma and her younger sister are aspiring prima ballerinas with their sights set on the prestigious Paris Opéra. Like a splendidly choreographed dance performance, Lena Sayaphoum’s art is rendered with grace, eloquence, and spirit. His soft, fluid illustration style and muted color palette hit all the right notes to intone this tender tale of discovery, growth, and familial relationships.

The Art of Milt Gross Vol. 1: The Judge Magazine Comics 1923–1924 by Paul C. Tumey (independently published) ~ Best Humor Publication

Humor knows no decade. Or century, for that matter. The screwball cartoons of cartoon virtuoso Gross show that the best humor is still fresh and hilarious after 100 years. This, the first in a series, presents hundreds of rare, revolutionary cartoons from Judge during the early 1920s, which formed the foundation for Nize Baby, Count Screwloose, He Done Her Wrong, and numerous other successes (for the definitive compendium, see Tumey’s Gross Exaggerations: The Meshuga Comic Strips of Milt Gross, 1926-1934, from Sunday Press). Everyone will identify with the schadenfreudenly-funny frustrations of Gross’s everyman characters who deal with life’s simplest incidents that hilariously snowball from bad to worse to worser to worsest. Plus, the enlightening commentary by historian Tumey adds insight and depth, noting how Gross often reworked his gags, basically stealing from and improving upon himself. With the master of cartoon pantomime, words can’t fully express our enjoyment. And that’s no Banana Oil.

Cornelius: The Merry Life of a Wretched Dog by Marc Torices (Drawn & Quarterly) — Best European Humor Publication

Never mind the Marvel and DC Universes. The best way to enjoy – and challenge – yourself this year is to tumble into the anarchic, delightfully absurd Cornelius Universe. At nearly 400 pages, Spanish artist Torices gleefully explores the entirety of the comics medium through deliriously shifting eras and spaces, which he renders in a madcap array of styles and textures. Cornelius gleefully homages and vastly expands upon everything from Frank King’s Gasoline Alley to European bandes dessinée. And humor knows no boundaries: as proven here, it can be both merry and wretched, hilarious and unsettling. It’s also a celebration of the art of comics, skillfully pushing the very boundaries of the medium. Rich with multiple interpretations, Cornelius generously rewards repeated re-readings.

Drawn to MoMA: Comics Inspired by Modern Art by Jon Allen, Gabrielle Bell, Barbara Brandon-Croft, Roz Chast, Liana Finck, Ben Passmore, Walter Scott, Chris Ware, others. (MoMA) — Best Anthology

Beginning in 2019, the Museum of Modern Art commissioned an array of comics creators with diverse styles and sensibilities to create new strips, using visits to MoMA as their inspiration. And this book rewards us with fresh, thoughtful short stories offering a variety of approaches – literal and internal – and perspectives – sometimes playful, often poignant – from talents such as Roz Chast, Gabrielle Bell, Ben Passmore, and Liana Finck. Each, in their way, offer insights on the many diverse modes of art appreciation: aesthetic, social, personal, etc. Truly praiseworthy is the book’s ability to inspire and incentivize readers to experience and engage with gallery works as well, and bring back their own stories. Oh, and did I mention that the book also comes with a tall, spectacular Chris Ware fold-out poster, suitable for homes and galleries alike?

The Novel Life of Jane Austen: A Graphic Biography by Janine Barchas & Isabel Greenberg (Black Dog & Leventhal/Greenfinch) ~ Best Reality-Based Work

Whether or not you’re an Austenite, you’ll find this book as an elegant, captivating study. Barchas’s astute and affectionate devotion to Austen plays out on every page. And Greenberg’s delicate art and soft color palette affords the reader a captivating tour of 18th century London society and a fascinating glimpse into the Pride & Prejudice author’s life from young lady with nascent writing skills to struggling scribe to acclaimed novelist. Projections of Austen’s inspirations for her fictional scenes and character are well defined via her family’s heartbreaking economic and literary struggles. As she comes to realize that she’s “never alone”, we can all be rewarded by so positive a view of life. (Incidentally, Austen’s 250th birthday was just celebrated on Dec. 16)

Precious Rubbish by Kayla E. (Fantagraphics) ~ Best Graphic Album–New

Visually striking and contextually disturbing, this book is ultimately cathartic. Daringly designed with vignettes, ads, and games – Kayla E.’s remarkable tribute to the versatility of the medium – it bluntly explores the author/artist’s life as she endures abuse, emotional and physical, and mostly from her sadistic mother. Her simple, almost cutout-like art is unquestionably moving, capturing her heartbreak and growth. And its bright, vivid colors – especially the shocking red – are intensely penetrating in every unsettling scenario. There’s a creepy familiarity to the surroundings, which a check of the end notes reveals to be true: many pages are inspired by the more wholesome, sanitized 1950s comics like Archie and Little Dot. If you can handle the emotional excursion, you may find some precious hope amidst the rubbish.

Paul Auster's The New York Trilogy by Paul Karasik, David Mazzucchelli, Lorenzo Mattotti (Pantheon Graphic Library) — Best Adaptation from Another Medium

City of Glass was revolutionary when it was first published back in 1995 – as an exceptionally well-done collaboration between Karasik and extraordinary artist Mazzucchelli – and the term “graphic novel” was relatively unknown. And on its own it’s justifiably considered a masterpiece, due in no small part to Karasik’s influence from Harvey Kurtzman, who he had as an SVA teacher, and Art Spiegelman, who he apprenticed for on Raw. And now we have all three of Auster’s brilliantly interwoven postmodern existential pulp detective stories in graphic novel form, with Mattotti’s art acting as center-story transition in illustrated novel and Karasik himself skillfully providing full-circle closure. These stories are essentially about writing – words – which Karasik and his two sterling collaborators have transformed into stories about words and images, so skillfully structured as to become most valuable as tutorials on communicating complex, intricate narratives – of loss, obsession, even meaninglessness – through creative, evocative visual storytelling.

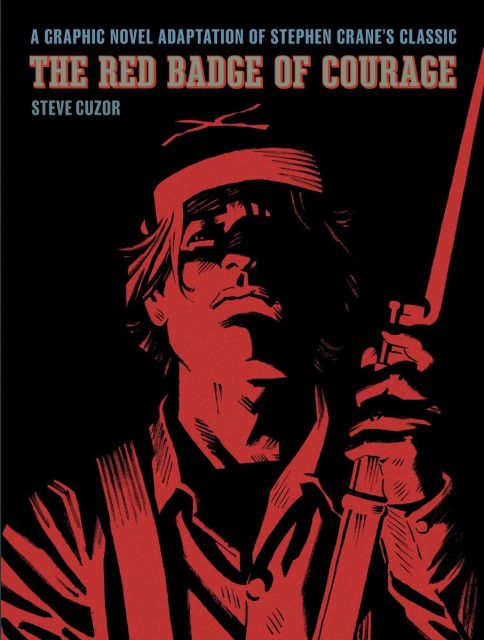

The Red Badge of Courage by Steven Crane, adapted by Steve Cuzor (Abrams) ~ Best International Adaptation from Another Medium

The Red Badge of Courage by Steven Crane, adapted by Steve Cuzor (Abrams) ~ Best International Adaptation from Another Medium

Sorry, kids: Cuzor won’t help you write your book report. Instead, he’s given us one of the most powerfully illustrated adaptations of a book you may ever read or see, capturing Crane’s emotional shock of combat as if Civil War photographer Matthew Brady was reporting on that very battlefield. This is an excellent, primal condemnation of soldiers’ terror of dying, of cowardice, and of the damned depersonalization of men reduced to nothing more than fodder. Stark yet subtle chiaroscuro drives home the story’s violent misery, enhanced by Meephe Versaevel’s nuanced coloring, rendering days with muted browns and moonlit nights with soft blues. Crane makes this story real, terrifying, and profoundly human.

Muybridge by Guy Delisle and Helge Dascher (Drawn & Quarterly) — Best U.S. Edition of International Material

For 25 years, Canadian cartoonist Delisle has been producing first-person graphic travelogues through Asia and the Middle East. Muybridge is something completely different, a classic American story of a ambitious immigrant coming to America, embracing innovation, then fame, rising and eventually falling. It’s a huge-scale biography of one of the greatest influences on early filmmaking, art, and comics, while reading like a Dickens novel. Delisle follows a Canadian tradition of conveying more information, more detail, with far fewer lines, and he uses this to great effect in illustrating Eadweard Muybridge's film and motion experiments while revealing them as prototypical comics. In fact, it’s not just a brilliant biographical novel: it's also a visual treatise on sequential movement that belongs in the hands of any student of comics as well as cinema.

Kylooe by Little Thunder (Dark Horse) ‚ Best U.S. Edition of International Material—Asia

This trilogy of intimate, intensely emotion-driven stories, unified through a cute, white monster named Kylooe is a heartfelt gem. First is a psychedelic fantasy of an outcast high schooler, a Princess Camille seeking her Little Nemo. Next is a melancholy romance for anyone who’s ever broken up with someone they wish they hadn’t. And finally there’s a father/son tale about government-mandated emotions that hints of Harlan Ellison. This deeply moving, eminently shareable book is smartly rendered by Little Thunder, a pseudonymous Hong Kong author/illustrator, with deeply moving stories that’ll make you wish for a Kylooe in your own life.

The Smythes by Rea Irvin, edited by R. Kikuo Johnson and Dash Shaw (New York Review Books) — Best Archival Collection/Project — Comic Strips

Irvin’s artistic legacy goes far beyond Eustace Tilley, his iconic monocled dandy and butterfly enthusiast who graced The New Yorker’s very first cover, with his Smythes among his more obscure works, most unfortunately, as it’s been an unheralded masterpiece. But this has been rectified by Johnson and Shaw with this gorgeous, deluxe, oversize highlighting from the strip, which originally ran Sundays in the Herald Tribune in – of course – New York in the 1930s, post-Market Crash. Every page is a chuckle and a half of clever and endearing banter between milquetoast John and Margie of the outrageous fashion sense. This collection reprints the best of five years of Irvin’s sweeping art and highlighting his eye for playful, innovative design as well as his graceful line. Of the millions of jokes about henpecked husbands and pretentious, social-climbing wives – hello, Maggie and Jiggs! – this is an undeniable classic. And among the back-page miscellany is Irvin’s witty 1943 Sunday funnies parody, Superwoman, which ran once before receiving a cease and desist notice from National, now DC Comics.

Lore Remastered by Ashley Wood and T.P. Louise (Simon & Schuster/Image) — Best Archival Collection/Project—Comic Books

Louise and Wood’s acclaimed, groundbreaking Lore is now reassembled for your reading pleasure. Part mesmerizing comic narrative, part text with intensifying illustrations, all serve as an engrossing and terrifying story of a woman searching for her father’s killer who discovers that mythic creatures, once banished from the world, are demanding to return. Newcomers to Wood’s art should find themselves enraptured by every image. This collection has added art pieces that astonish on their own. This is one for all lovers of fantasy.

Jordan Crane, Goes Like This (Fantagraphics) — Best Writer/Artist

You’ll find this in the twisted-mind section of your local bookstore. Within its trip-inducing cover is a daring compendium of narratives that span genres from warped Western to distorted Hitchcock to familiar, bitter relationships to oddly adroit wordplay and more. Crane’s wide variety of experimental, offbeat tales, splash pages, and interstitials evoke Frank King, Geoff Darrow, Seth, Warhol, William Morris, Shag, and, well, his own memorably sensation-inducing genius.

Elsa Charretier, The City Beneath Her Feet (Dstlry) — Best Penciller/Inker and Jordie Bellaire, The City Beneath Her Feet — Best Coloring

In this bloody action/thriller/romance, Charretier’s layouts explode and just keep exploding, right from the “La Femme Nikita”-style opening. Even in seemingly simple straight-on camera monologues, her slightest of strokes give us telling expressions with bits of business that reveal the character’s pain – tiny tears welling – or bitter joys in suffering smiles. The foregrounds and backgrounds meld into moods you can feel. This is nonstop breathtaking exhilarating, storytelling.

And Jordie Bellaire’s in top form. Her colors are brilliant, as in both vivid and radiant. She breathes intensity into the drama and the action by choosing colors you don’t often see, in line holds and panels in specific tones that yell at you to pay attention! Throughout the whole book there’s never a dull page. Never.

Jakub Rebelka, The Last Day of H.P. Lovecraft #1-2 (Boom Studios) — Best Painter/Multimedia Artist

Red can be a raw, intensely disturbing color, and French artist Rebelka uses it to express the slow demise of horror master Lovecraft. Disconnected, bloodshot eyes are awash in crimson goo. A red-striped lighthouse morphs into a torrential scarlet sea. Blood courses down a hospital wall. A ruddy Cthulhu haunts the background. Lovecraft himself is perpetually presented – in the hospital, with his wife, with Houdini – in unsettling vermillion. Then there are the grays: the gloom that consistently surrounds Lovecraft’s psychological distress. In paint and ink, Rebelka unnerves us to our very heart on each and every page. After having read The Last Day … you may never view red the same way.

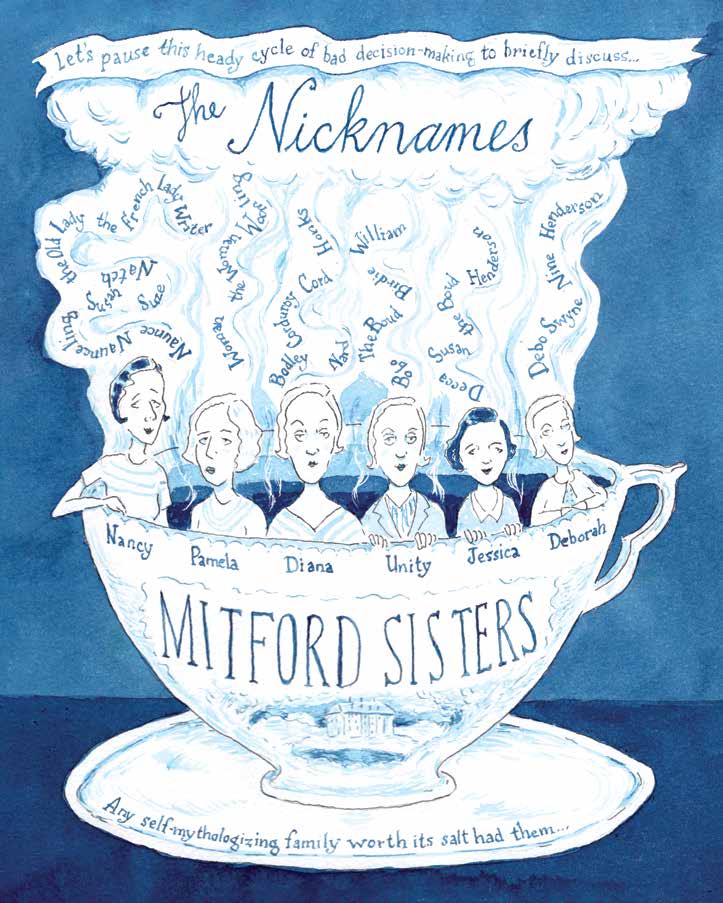

Do Admit: The Mitford Sisters and Me by Mimi Pond (Drawn and Quarterly) — Best Graphic Memoir and Mimi Pond, Do Admit — Best Lettering

Best Memoir Awards aren't typically given to a true tale of six sisters in England, starting at the turn of the 20th century, but there you go. A study in contrasts, Pond has smoothly and skillfully woven her 1960s working-class San Diego childhood into the lives born to British aristocracy.

Also, Best Lettering Awards aren't typically given to works that aren't Todd Klein variations, but every single letter of every word in Do Admit is exquisitely hand-lettered on every page, from cover to end. And I defy any other graphic novel this year to claim anywhere near the skill, imagination, and wit Pond's put into the variety of expressive texts and talking, serif, sans, script, blackletter. And she further enlivens her narrative with illustrations of newspaper and magazine covers, movie posters, maps, and hand-written... memoirs, all bursting from panels and pages, designed, sized, and styled with the greatest dexterity as well as spirit and verve. Best Graphic Novel of the Year? Yes, and not just admittedly but absolutely!

ImageTexT, v. 15 #3, edited by Anastasia Ulanowicz — Best Comics-Related Periodical/Journalism

ImageTexT’s most recent online journal has four exceptionally solid, smart, illustrated features with a diverse array of relevant political themes: an exploration of Chris Ware’s New Yorker covers about school shootings; a critical study of anthropomorphism in Soviet political cartoons during WWII; a tough examination of Australian cartoonists’ brutal attacks on Chinese men in the late 19th Century; and an in-depth analysis of the blurred lines between mainstream and underground in the 1970s, citing Denis Kitchen’s Arcade, Bill Griffith/Art Spiegelman’s Comix Book, and Steve Gerber’s Howard the Duck. And hey, it’s absolutely free for you to read right now.

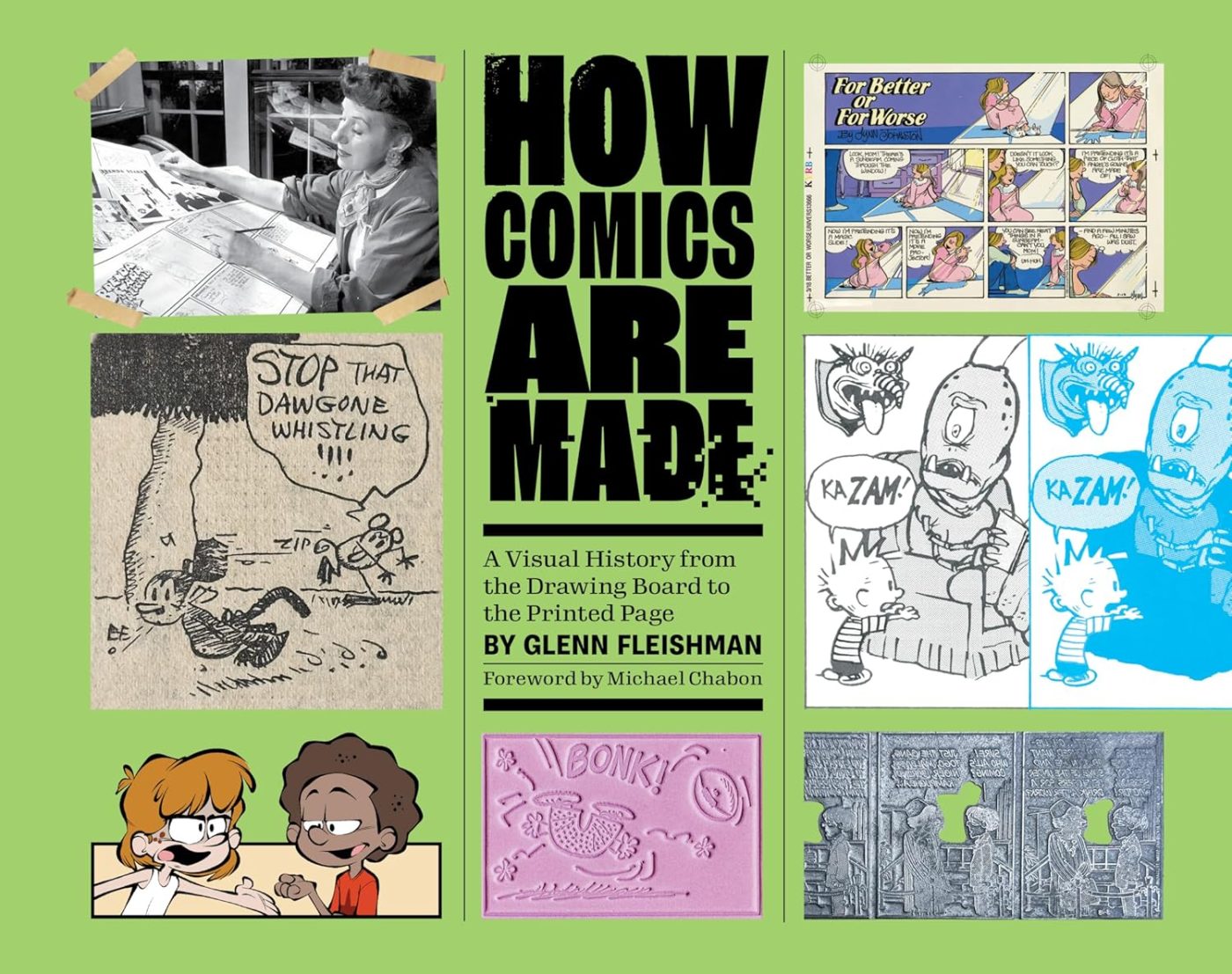

How Comics Are Made: A Visual History from the Drawing Board to the Printed Page by Grant Fleishman (Andrews McMeel) — Best Comics-Related Book

When reading a newspaper comic strip, how often have you wondered about the physical process of how they’re created? This question is hardly recognized, much less explored in-depth, in most comics histories. Well, throughout this informative, entertaining book Fleishman provides everything you need to know about the technical mechanics of the medium, which does a great deal enlighten us and enrich our enjoyment. His intelligent, humorous commentaries, with anecdotal asides, are simply a delight. All the information is presented in straightforward style, and expertly enhanced by hundreds of photos of massive machines and other tangible materials of mass reproduction of strips from classic – lookin’ at you, Yellow Kid – to contemporary to web. And as our Sunday funnies fade into the digital aether, why not spend a few post-paper weekends curled up with a comfortable copy of How Comics Are Made?

Back to Black: Jules Feiffer’s Noir Trilogy by Fabrice Leroy (Rutgers University Press) — Best Academic Work

The more the opportunity to introduce Feiffer to the world, the better the world becomes. And Leroy deserves the highest praise, not only for astutely situating this three-volume loving homage to noir within the broader context of his extraordinarily prolific and diverse art careers but also for his detective work on these detective stories, with insightful analysis of the ways in which Feiffer's loving homage to noir astutely uses American history from the Great Depression through the McCarthy era to incisively satirize and subvert our present culture. Also noteworthy is Leroy's appreciation of Feiffer's visuals: hiscreative reconfigurations of hard-boiled cinema devices into his subtle, sophisticated layouts and unique graceful, limber linework.

Comic Book Apocalypse!: The Death of Pre-Code Comics and Why It Happened, 1940–1955 by David J. Hogan (Schiffer) — Best Scholarly Work

This informative, engaging history takes an unblinking, insightful analysis of midcentury America's evolving culture, from the start of WWII to the institution of the CCA, which explores beyond the usual sex, crime, and horror comics suspects. Visually rich, with its clean page layouts and hundreds and hundreds of large, sharp color reproductions, this is the most attractive study of that censorious era to date. More scholarly books should be gifted with such luxurious design.

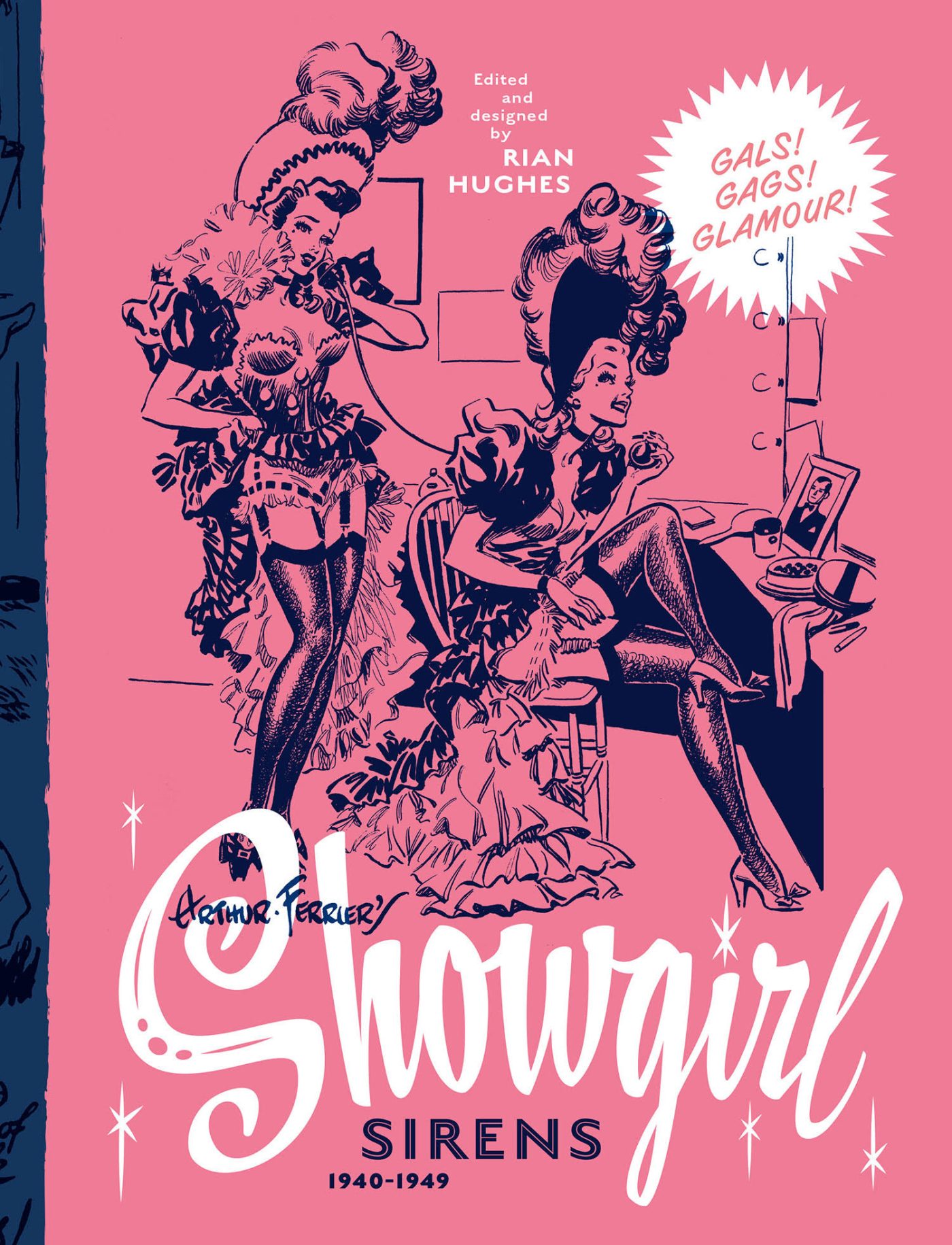

Arthur Ferrier’s Pin-Up Parade! by Rian Hughes (Korero Press) — Best Publication Design

America can count Russell Patterson, Dan DeCarlo, Bill Ward, and George Petty as its top echelon among classic cheesecake pin-up artists, and in the UK, Scotsman Arthur Ferrier is most highly – and rightfully – held in the highest esteem for his elegant, sophisticated renderings of the female figure during pin-up’s golden age. His prolific output ran from the 1930s to the ’60s, often in humor magazines such as Punch and Blighty over several decades. And now, Korero Press has released a magnificent, oversize, comprehensive, three-volume compendium with nearly 1,000 pages, including hundreds and hundreds of his brilliant illustrations, primarily single-panel gags but also comic strips and a variety of publication covers, adverts, and other ephemera. Ferrier's fluid linework – capturing his women's joyous spirit, expressive gestures, and even their evolving fashion styles - is simply a delight to behold. Plus, a couple dozen pages of each book are devoted to his own essays and correspondence course lessons on his craft. Most impressive for me is the superlative skill with which this dazzling, deluxe collection has been luxuriously packaged to a fare-thee-well with the highest production values by Britain’s master graphic designer/comics artist Rian Hughes. In 2020 Hughes merited two Eisner nominations, “Best Publication Design” and “Best Comics-Related Book” for his superb Logo-a-Gogo, also published by Korero. And here, he’s outdone himself. He’s combined Ferrier’s art with marvelous midcentury colors and typography onto the solid, sturdy cloth-textured slipcase box as well as each of the hardback covers. And then there’s the ribboned bookmarks, patterned endpapers, and luxurious cotton matte paper stock and crisp inks to enhance the vintage aesthetic. Pin-Up Parade! is easily the most spectacular publication of the year, bar none. It’s available in its entirety in England but at this time the first, Showgirl Sirens (1940-1949) – which includes an insightful intro into Ferrier’s career by Hughes – can be purchased in the U.S., with the other two, Burlesque Bombshells (1949-1954), and Cabaret Cuties (1954-1968), in the offing.

Best Digital Comic — C’mon: it’s the 21st century and this category is totally irrelevant. Onward!

***

Alex Dueben

The Ephemerata: Shaping the Exquisite Nature of Grief, Book One by Carol Tyler

Breadcrumbs by Kasia Babis

Spent by Alison Bechdel

Where There's Smoke, There's Dinner by Jennifer Hayden

Simplicity by Mattie Lubchansky

Paul Auster's New York Trilogy by Paul Karasik, Lorenzo Mattotti, David Mazzucchelli

The Weight by Melissa Mendes

Tongues by Andres Nilsen

Ethel Carnie Holdsworth's This Slavery by Scarlett and Sophie Rickard

The Once and Future Riot by Joe Sacco

The Complete C Comics by Joe Brainard, et al.

Hothead Paisan by Diane DiMassa

Terminal Exposure by Michael McMillan

Mafalda: Book 1 by Quino, translated by Frank Wynne

***

Malcy Duff

As another year comes to an end, inside my home there are no seasons, and my bookshelves look like they contain the beautiful, ripened fruit of a perpetual stagnated tree. Returning though, I fear that the fruit will finally fall before being picked. Captain Carrot and the Amazing Zoo Crew still swing from the branches of these bushes, as if their powers of flight were just shenanigans on a bungee cord, awaiting the lost weekend in their company I crave. And too many other tomes are still, so very still, and silent, just their bright spines remaining joyful and noisy unfaded from elsewhere sunlight. As I look again in my bookshelf’s direction however, I am safe in the knowledge that some pages have been turned. I realise this year’s reading has been mostly focused on reading about cartoonists. They have inspired me in different ways:

- What Cartooning Really Is: The Major Interviews with Charles M. Schulz has reduced my swearing dramatically.

- Lynda Barry's interview in The Comics Journal #132 has encouraged me to find a friend I can phone when I’m inking.

- The Daniel Clowes Reader has made me want to take up badminton again.

- And Three Rocks by Bill Griffith has prompted me to start saving for three more drawing boards to get to the magic number of 4.

Recently I have been following the line of David Berman on lucky lyric sheets and his Portable February collection. And I have been returning to The Angriest Dog in the World, celebrating that special man.

Sometimes we don’t get around to eating all the apples on my Dad’s apple tree, and they land on the ground and start to rot. And that’s ok.

Still ... I’m glad comics never go rotten.

***

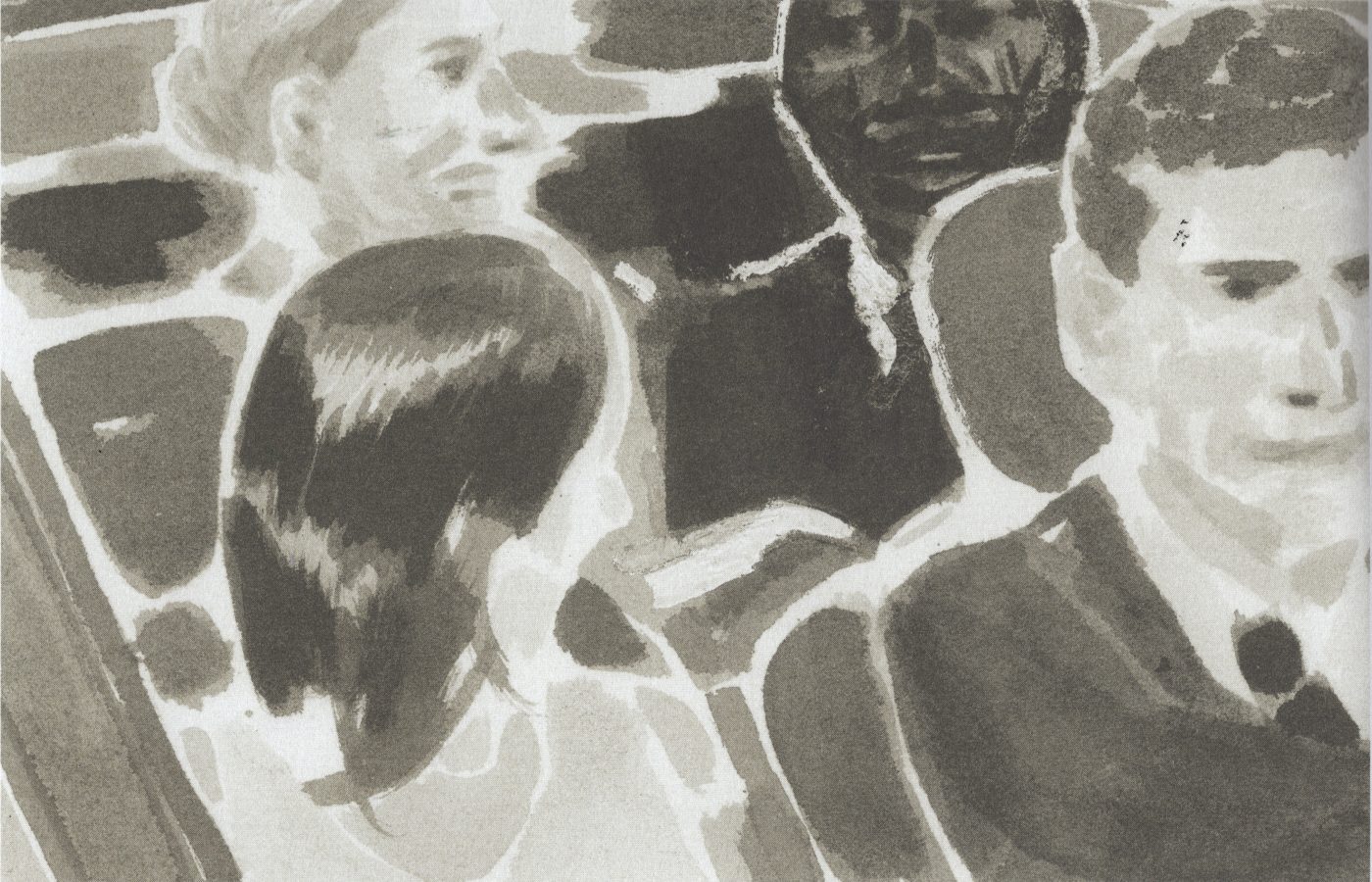

Panel from Misery of Love.

Panel from Misery of Love.Austin English

Below, I've picked 3 books that were all important to me for the same reason: when you have been involved with comics for a long time, as an artist or reader , there will be inevitable moments where you question if the medium is capable of all that you want from it, you begin to doubt your deep involvement in the artform---then, if you're lucky, at just the right moment, works like the ones listed below emerge and affirm all your most utopian hopes for the artform. If your faith is wavering in comics (and if you really love them, you must have this crisis from time to time), read any of these books:

Misery of Love by Yvan Alagbé

I will be writing about this book at length in the upcoming print edition of The Comics Journal, here is small excerpt of what I wrote there:

In a New York Times review of this book by Sam Thielman, a character named Michel's worse transgressions are listed, including that he "was in love with a woman who wasn’t his wife." Thielman read Misery of Love sensitively, but I found far more potent moments of Michel’s violence (both sexual and otherwise) in my readings of the book. Here we see how this work can be made anew upon each reading. Thielman stresses that he read the work multiple times (and recommends other readers do the same), but finds different fault lines than I did. Alagbé, in my reading, suggests that Michel has engaged in far worse transgressions, which Thielman ignores or does not see. In one sequence, his daughter Clare’s childhood self is confronted by cries from her mother "it was you who wanted him to be in love with you," "it was you who led him on," "little fool! how did you come up with all this?" One might expect an insinuation like this to occupy the climax of a narrative, but for Alagbé it is one note in the whole blink-and-you-will-miss-it focus and you’ll feel the tragedy, only for it to vanish by the next image — with the mist of it lingering back and forth across the book. One (to me, horrible) image shows Michel cradling Clare, during her childhood, in his arms. Alagbé uses the soft ink wash he employs throughout the book to a shocking effect here: the weight Michel applies to Clare is forceful, his face a distorted mess of wash, his hands cruel. This image communicates brutality, even in isolation. If we looked at it apart from the rest of the narrative, it would still provoke and we would draw conclusions from it, though more visceral than certain. Placed alongside 463 other images, all of them with their own unique weight, it pulsates. As we approach our fourth or fifth reading, the image lodges in our mind, infecting how we look at previous and subsequent sequences. The miracle of Misery of Love is that all 464 images carry the same force of reverberation.

Alagbé presents us a "graphic novel" that defies the way in which we have grown comfortable reading graphic novels, which is as prose. This work is actually graphic, in that the images contain meaning independent of textual assistance. In a non-poetic work of art, there are times when information is presented artlessly: "he got in the car," "he ate dinner," etc. An elegant prosaic entertainer can make dead moments like these part of his rhythm, with meaning beyond what is necessary left aside. The plot, after all, must move forward at times. Misery of Love denies itself such license. One image gives us Alain (Clare's boyfriend, who is of African descent) in a car, next to Clare. Alagbé, without telling us, without prodding us, without begging for our understanding, depicts Alain’s at a remove from Clare. His stance, the tension of those seated in front of him, the contrast between Clare’s face and his, an ever so subtlety exaggerated ratio of proportions between Alain and his fellows — it’s as if Alagbé collages Alain into the picture, the expression he wears believable but at the tip of total remove from the scene he occupies. This is how the picture confronted me on my fifth reading. In my earlier attempts, I ignored it entirely. The anger within this drawing is all the more remarkable for how it can be shoved aside until the reader breathes life into it.

The book concludes with a smile, one that, once more, throttles us back through the earlier graphics, casting new perspectives on all that we have just witnessed. The greatest works, in thought and in art, are not systematic but living organisms inviting participation of the heart and mind. With Misery of Love, what this final smile means can never be solved, but can be felt with increasing depth the more that is given to the book.

The Devil's Grin Vol. 1 by Alex Graham

I truly think this is one of the best comics of the past decade, maybe one of my favorite comics ever. With graphic novels as the dominant delivery system for comics going strong for over a decade, most GN's remain single-issue comic ideas stretched out to an undercooked 200 pages (or more). Devil's Grin is worth the pages it's printed on, there's no padding. And while it is long, ambitious and dense, this is a comic much more than it is a novel, its writing is in the drawing (a cliche we hear all the time in comics, but this book can explain the truth at the heart of the cliche) and I love how it's drawn. While certain panels don't match the hyper-perfection of alt comics at their most ascendant, there's no way anyone else besides Alex Graham could draw this: she gets the expressions exactly right in a way that a more "perfect" drawer could never do, all of Noel Sickles printed work (which I adore) combined can't equal the writing (and by that I mean comic drawings) that Graham's cartooning is built on. It's as if Graham figured out how to make the "great American alt comic" by synthesizing the approaches of alt comics literary ambitions with the "draw in your own way" mini-comic movement, which are more opposed than people think. If I was to show a panel from this work to a comics person who swears by the craft of, say, an Archer Prewitt, it may leave them cold. But Graham has, I believe, outdone so many cartoonists who wrestled with a dual loyalty to airtight craft and ambitions of "writerly" comics. Devil's Grin is wrestling with neither of those things, it lays down a gauntlet of its own excellence. Unlike your normal book-of-the-moment faux sensitivity, this work contains a level of emotional intelligence that so many cartoonists struggle to even approach let alone ever come to achieve. While there are intense/"transgressive" moments happening in Devil's Grin, this should not obscure that the book has, as its main focus, an investment in how people treat each other and a sense of moral clarity that most muddled graphic novels never even bother to broach.

From the Complete C Comics.

From the Complete C Comics.The Complete C Comics by Joe Brainard (and many more). Essay by Bill Kartalopoulos, Foreword by Ron Padgett.

Looking at this new C Comics collection brought up some thoughts. Since the early '00s, poetry comics DID happen, but they did NOT happen in publications like Ink Brick. There is the famous Jean Cocteau quote about a child prodigy poet, Minou Drouet. When asked what he thought of her, Cocteau said "all children are poets, except Minou Drouet." That's how I feel about Ink Brick. All comics [have the potential to be] poetic, except those published in Ink Brick, comics that just graft cartooning onto outdated and conservative poetic forms. What's happening now, at the heart of comics fringes, is something different than simply breaking up a sentence over many panels and calling it "comics poetry." Instead, many young artists focus on publishing work that is a short exploration of a thought or a feeling, and this exploration unifies text and imagery in the pursuit of eliciting feeling from the reader. Instead of naturalistic fiction (which dominated alternative comic spaces in the '80s and '90s) we begin to see less and less focus on characters. Even autobio seems to be disintegrating. Self-publishing art cartoonists now often begin with an unnamed person speaking directly to the reader, with great focus on how such a person poses on the page, how they carry their weight. We see, in these kinds of comics, an avoidance of epiphany and an avoidance of resolution, though (crucially) without an avoidance of feeling.

If we attempt to trace the origins of this, I'd say Doucet looms large, though I'd narrow her influence to before her concessions to alt comic conventions got the better of her (New York Diary and everything that came after, until her return to form with Time Zone J). In an early Doucet strip, called "Month of December," Doucet stands on a bridge and says "Christmas is coming." She sniffs her nose, "it's cold." In the final panel, she hurls herself off the bridge: "... and I'm gonna die?" That is the entire strip. Is it about suicide? Depression? Maybe, but no simple prosaic judgement can contain the strips power. So many emerging cartoonists work in this way today. This makes sense, as pure comics get at the core of poetry better than poetry itself could. Poetry strives to make expression new while working with an inherited set of symbols, the letters of the alphabet you write your poetry in. A comic like Doucet's goes farther, she does not write "I stood on the bridge and began to speak to you." She draws the bridge, her description of this specific bridge is already charged with a poetry that the letters themselves could never contain, no matter how you place them or rearrange them (all the tortured word placement of modernist poetry could have been solved, it seems, with drawing). Traditional cartoonists worked hard to make the bridge disappear. If Milton Caniff's story required him to draw a bridge, he'd do it perfectly, but so perfectly that you would not notice it or linger on it, the bridge merely a prosaic detail to connect point A to point B, no matter how proudly he drew it. Doucet allows the charge of her expression to be seen in every line, you ignore nothing, it's all part of the whole, just as nothing can be discarded or ignored in poetry.

Doucet, and the generation that embraces her approach, is not like the group of avant-garde poets who made C Comics. Joe Brainard and his ilk lived and breathed what poetry was and is, they devoted their life to it. When they sought to make comics, the tools of poetic expression were already on call within them, and the tools were finely honed. The work in C Comics feels mature and exact, work made by people conscious of what they were doing. Poetry comics circa 2025 are most often made by those with no (or little) interest in orthodox poetry, but instead in how comics can be used for self expression. This search for how to use comics in a mature way has been subverted and derailed for a century. When someone taps into the poetic potential of comics, you see it happen on the page, you feel the charge, "finally, this is how it can be done!" Lately, I see this moment of conception everywhere, all the parts coming into place organically and the thrill of artistic gestalt happening in a way that it has really never happened before, the absolute triumph of raw artistic discovery. You'd think C Comics would connect to this, but it feels oddly distant, not so much a relative to today's explosion as it is an acquaintance who, if you come to think of it, you never actually met.

And yet, despite this disconnect: as contemporary underground and fringe comics lean deeper into their poetic destiny, it is very important that this book is out now. C Comics is a tome that can now be corresponded with, there is enough strength in contemporary and organic poetic comics that the community making them won't be bulldozed by what is within this book ("it's already been done"). Instead it can act as a prophecy that you missed, and reading it now is exhilarating in its affirmation but not so influential as to change the flow of where we are already headed.

Post Script: I haven't finished Melissa Mendes' The Weight yet, but I read the early chapters years ago and found them incredible. This list wouldn't be complete without mentioning this book that I look forward to reading in full in the new year.

***

Jim Falcone

I’ve been on a monthly comic embargo since I left high school, but 2025 was the year to reel me back in. Kieron Gillen and Caspar Wijngaard started knocking down the dominos they’ve been setting up for the past 10 issues of Power Fantasy. Christopher Priest's essays at the end of Marvel Knights: The World to Come have been just as engaging as Joe Quesada’s art. But without a doubt Absolute Martian Manhunter was the mainstream comic of the year.

Deniz Camp and Javier Rodriguez are working in the Vertigo-tradition: reimagine a dusty DC IP, let the writer cram in as many purple prose captions as they need to describe the human condition, and pair them with an artist who can work outside the current house style. Probably their greatest achievement is making a comic with art that communicates instead of just illustrates. The fourth issue of the series starts with the cosmic-bringer of bad vibes known as “The White Martian” drawn like the silhouette on a men’s bathroom sign, with a black body and white circle head. In the next panel he lifts his head from his neck, then in the third he places it into the sky on the fourth panel, creating a heat wave that drives an entire city into a homicidal frenzy. Later in that same issue, the metaphorical enlightenment-golem known only as “The Martian” grabs a ray of white sunlight reflected in the protagonist’s eye, stretches it in his blocky hands, and separates it into three circular colors: red, green, and blue, the three colors that make up visible light. He overlaps the red and green–coincidentally the same colors used to signify the presence of The Martian throughout the comic–to create the color yellow, which he then places onto the city’s horizon as a setting sun, calming the madness and making everything right. It doesn’t make much sense explaining it, but you’ll love it when you see it.

In the indie scene, I read some great stuff this year. Harper B’s Bring Me the Head of Susan Lomond was an extremely enjoyable one-shot that proves that funny comics usually have funny art. Corinne Halbert’s still finding fresh and funky ways to express her psychological journey to happiness in her newest installments of Scorpio Venus Rising. Audra Stang’s Another Year comics on Instagram are expanding the lore of Valley Valley and Idella Delle in tiny snippets that leave me wanting something longer. I also had the pleasure of picking up the first issue of Monograph Magazine at this year’s MICE Expo: a fanzine edited by Ivy Lynn Allie, E.B. Sciales, and Warren Bernard focusing on single panel cartoonists. This inaugural issue goes over the life of single panel cartoonist and first woman member of the National Cartoonists Society Hilda Terry. These were all small press triumphs, but if I had to choose a favorite indie of this year, I’m going with the obvious choice.

I might be one of the four people currently reading Love and Rockets who’s closer in age to Tonta than Maggie. Life Drawing is the second trade starring Jaime’s new protagonist and her circle of friends/family. It’s nice to see Tonta get some breathing room after her last story, which felt like she was competing for attention with her pulpy family drama. Here we get an intergenerational crossover with Maggie and Ray while also getting to meet some of Tonta’s peers — I’m personally attached to the bug-eyed comic-lover Gomez, whose life feels closer to where I was at as a teenager than the more free-range Tonta. It’s a little disappointing that we only have 130 pages after ten years. Even two back-to-back weddings felt understated, but this collection gives the feeling that Jaime’s working up to something big. Until then, I’ll be reading and rereading what I have, just like with all of Jaime’s other comics.

***

From Do Admit!

From Do Admit!Andrew Farago

2025 was a terrible year in many, many ways, but it was a great year for comics. Here's a dozen or so of my favorites from the past year:

Do Admit: The Mitford Sisters and Me: Mimi Pond's books are always great, and she just keeps getting better.

Spent: Enter the Bechdelverse? Alternate reality Alison Bechdel hangs out in Vermont with the Dykes to Watch Out For cast and it's an amazing read.

Raised by Ghosts: Briana Loewinsohn's been one of my favorite minicomics creators for years, and her graphic novels are even better.

Life Drawing: Jaime Hernandez has been so consistently great for so long that people don't even comment on it when he drops another classic. The Love and Rockets curse.

Absolute Batman: Extreme in all the best ways. Just a blast.

Transformers: Another nostalgia trip, but a fun one. The '80s Transformers comic book we see in our heads when we think of what we were reading 40 years ago. The G.I. Joe and Void Rivals tie-ins from Skybound have been a lot of fun, too, and I'm glad that Larry Hama's still writing a monthly G.I. Joe comic and hope he gets to keep on doing that as long as he wants.