Zach Rabiroff | September 18, 2025

Peter David, the writer known for a long and inventive run on The Incredible Hulk, his copious work on Star Trek comics and licensed novels, and a bewildering number of comics, prose stories, editorial columns, animation scripts, film and television treatments, news stories, and blog entries died in a hospital bed on May 24, 2025, having suffered the latest in a series of strokes and heart attacks that had mounted in severity over the course of 13 years.

Peter David, photo by Kathleen David

Peter David, photo by Kathleen DavidHere is what two fans on the internet said in 1985, after David had just published his debut story arc as a writer on Peter Parker: The Spectacular Spider-Man. “I felt a sad twinge…mostly due to the powerful scripting by Peter David,” wrote one. “With David as regular scripter on this title, I think I'll add it to my list. This guy's good.”

“David has got his characterizations down perfectly. His writing is on a par with [Frank] Miller's during his initial DD's,” wrote another. “I really don't remember a talent surprise like this since Alan Moore appeared on the scene.”

It’s strange 40 years later to see David’s name appearing in such company, but we have to remember that the writers of those comments had the benefit of surprise. Peter David, in 1985, still felt completely unexpected to Marvel Comics readers: he had emerged seemingly from nowhere, though not for lack of trying. The New Jersey-raised son of two immigrant Jews (Gunter, a newspaper reporter who fled Germany under Hitler, and Dalia, born in British Mandate Palestine), David inherited from them the hustling instincts of the new arrival in America: the thoroughgoing willingness to be a jobber in the name of a steady buck.

Clockwise from left: George Takei, Brad Takai, Peter David, and Caroline David. Photo by Kathleen David

Clockwise from left: George Takei, Brad Takai, Peter David, and Caroline David. Photo by Kathleen DavidComics were a part of this early life, but only a part: one aspect of a general interest in the sci-fi gestalt of the Baby Boom generation (Star Trek, The Adventures of Superman, Tarzan, Harlan Ellison), and always paired with an equal and opposite sense that creative passions had to be balanced by professional duties. In his late memoir Mr. Sulu Grabbed My Ass, David recounted his father’s verdict on David’s early interests: “Your hobbies are nice, but you can’t make a living out of science fiction and comic books.” So David’s early career consisted of a bewildering variety of freelance assignments as a hired gun with a typewriter: newspaper articles (thanks to a leg up from his reporter father), short stories, book and movie reviews, and a staff position in the sales department of Playboy Paperbacks (for which, his friends say, he also moonlighted writing erotic fiction under names other than his own). And it was thanks to that scattershot background that David ended up finding his way into the mildly lucrative field of comics journalism, through the pages of Comics Scene magazine.

The founding editor at the magazine, Robert Greenberger, who would go on to be a lifelong friend and professional collaborator of David’s, remembers the circumstances that led to David’s first work. “It was just about the time [Playboy Press] shut down the entire imprint,” Greenberger says. “So Peter was suddenly out of a job…I get in touch with Peter and I said, ‘Look, we're a nationally distributed newsstand magazine. Not everybody knows what the direct market is,’ – This is 1981– ‘Can you go interview some people? Go figure out how to explain what the direct market is, and how publishers are capitalizing on it to build their audiences.’

“And Peter said, ‘Sure, I can do that. I've got journalism training. Not a problem.’ He goes in, he interviews a number of people, including a really long lunch conversation with Carol Kalish, who at the time was heading up the direct sales marketing at Marvel, and they hit it off.”

And so, by a circuitous route, David ended up on the staff of Marvel Comics. Though not, as it happens, on the popular side of it. One of the curious realities of 1980’s Marvel, recounted by all of the veterans of the era, was the mutual rivalry between Jim Shooter’s editorial department and the three-person staff of the marketing team, on which David was stationed. “The only reason he was down on our floor, the 6th floor, was that he was scratching for work,” says Larry Hama, an editor at the time. “Everybody on the creative floor just thought of the 10th floor [corporate] people as being suits, and bean counters, and PR people.”

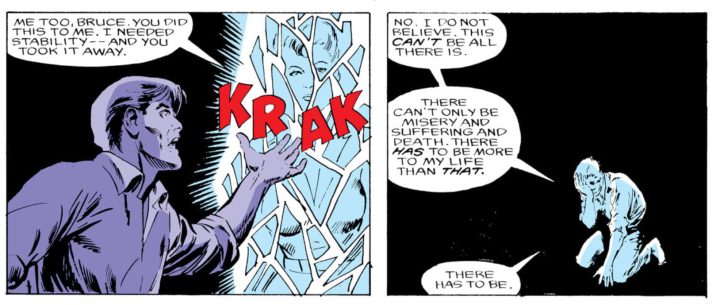

panels from "Piece of Mind" (Marvel, 1987) written by Peter David, pencils. by Dwayne Turner, inks by Tony De Zuniga

panels from "Piece of Mind" (Marvel, 1987) written by Peter David, pencils. by Dwayne Turner, inks by Tony De ZunigaDavid, consequently, found himself the recipient of a kind of low-key shunning when it came time to work with the editors, writers, and artists whose books David had to promote. Jealousy might have played some part of it: during the years David was on staff, the direct market’s share of Marvel’s total sales grew from 20% to 70% of the publisher’s total, according to retailer Chuck Rozanksi. But it could also lead to friction with colleagues and staff alike. When David promoted an issue of John Byrne’s Alpha Flight by distributing pages to retailers of a surprise character death, Byrne was incensed, sparking a rivalry between the two that would play out publicly in the fan press for the next decade. Likewise, when David and the marketing department participated in a hoax on the comics press about a fictitious “backward” Spider-Man issue (which readers would need to read by way of a mirror available at comic shops), he became the focus of a brief but intense fury of fan-press ire. It was an early example of a tendency to court controversy that David would keep up for the rest of his life.

But it was as a writer that David had increasingly focused his ambitions, and the fact that he achieved them was thanks to Larry Hama’s erstwhile assistant, soon to become the editor of the Spider-Man family of books, Christopher Priest (at that time still going by the name of Jim Owsley). Priest, by his own account, had the benefit of ignorance: as a young (hired by the company at age 17) editor and a protege of EIC Jim Shooter, Priest was himself something of a black sheep among Marvel editors. His willingness to hire the unhirable became an advantage.

“I liked Peter, and I think we went out to lunch at some point and we got off really well. And we became friends,” Priest says. “And I would occasionally hear complaints about Carol and I don't know if the complaints were grounded in anything. And because I really didn't care. And, sorry, I probably should have cared, but I just didn't pay a lot of attention to it. It was all just noise.” For all his guarded cynicism about unsolicited submissions, Priest was taken by surprise when his friend turned out to be an aspiring writer.

Spider-Man #103 (Marvel, 1984) written by Peter David, cover art by Rich Buckler

Spider-Man #103 (Marvel, 1984) written by Peter David, cover art by Rich Buckler“He just sprung it on me one day,” Priest says. “We're having lunch or whatever, and he goes, ‘Would you mind taking a look at one of my scripts?’ And I just go, ‘Oh, hell.’ I immediately thought, ‘How did I not see this coming? What's wrong with me?’ So it kind of came out of nowhere. In all of our travels, and our personal buddy time, at no point did he say, “By the way, I want to be a comic writer.’ But he's my pal and, all right, I’ve got to read this thing. So I took the script from him. It took me a while to get to it, but I started reading it and I was very surprised at his level of craft, and how readable the thing was. It had something to do with Leopold and Loeb, a murder mystery. I got to the end of the script, and there was some sort of twist that I didn't see coming. And that's hard to do with me. And I went down the hall and I said, ‘Here, fill out this voucher because you got me.’”

Response to the fill-ins was good, and in July of 1985, David became the new permanent writer on the Peter Parker: The Spectacular Spider-Man series, making his debut in the time-tested manner of killing off a notable supporting character in “The Death of Jean DeWolf.” Looking back from the distance of four decades, it’s not hard to see why fans responded the way they did. After decades of writers and artists playing variations on the basic jazz riff of Steve Ditko and Stan Lee’s Spider-Man, David’s interpretation was something else: street-level, claustrophobic, soaked in a genuine sense of tension underneath the steady stream of wisecracking one-liners.

It was, in other words, very much like Frank Miller’s top-selling run on Daredevil, and Priest doesn’t pretend the similarity was accidental. “That entirely came from me, because Peter was capable of writing anything I needed him to write,” he says. “He could do spectacularly funny, broad humor that would just leave you in stitches. He could do Galactus Eats, the Baxter building big action stuff…So Peter Parker, I wanted to make the more grownup book. [It] took place at night, and [Spider-Man] wore the black uniform, and they had more grownup stories.”

Giving the assignment to Peter David, whose inclinations then and later tended toward levity and winking mockery rather than grim drama, was more of a surprise. But the tension could work remarkably well on the page. At one point during his Peter Parker run, David came up with a story in which Spider-Man has to confront a super-powered pre-teen whose abilities have gone out of control. At Priest’s prompting, David’s initially happy ending instead closed with an abrupt set of final panels in which the young antagonist is killed. Peter David the lighthearted showman and Peter David the psychologically probing artiste were merging into an encapsulation of 1980’s superhero comics. The fans loved it.

Editor in Chief Jim Shooter, however, did not. By the mid-80’s, Shooter was taking an increasingly interventionist role in his company’s books, frequently revising, rejecting, and insisting on multiple rounds of changes within his various editorial offices. David’s cleverness as a writer was a part of his appeal – one story was modeled on the formula of Kurosawa’s Rashomon – but it was too much for Shooter to bear. Eventually, Priest found it easier to fire his star writer than to keep pace with his Shooter’s complaints. David, he says, still held the grudge three decades later: another distinctive Peter David trait.

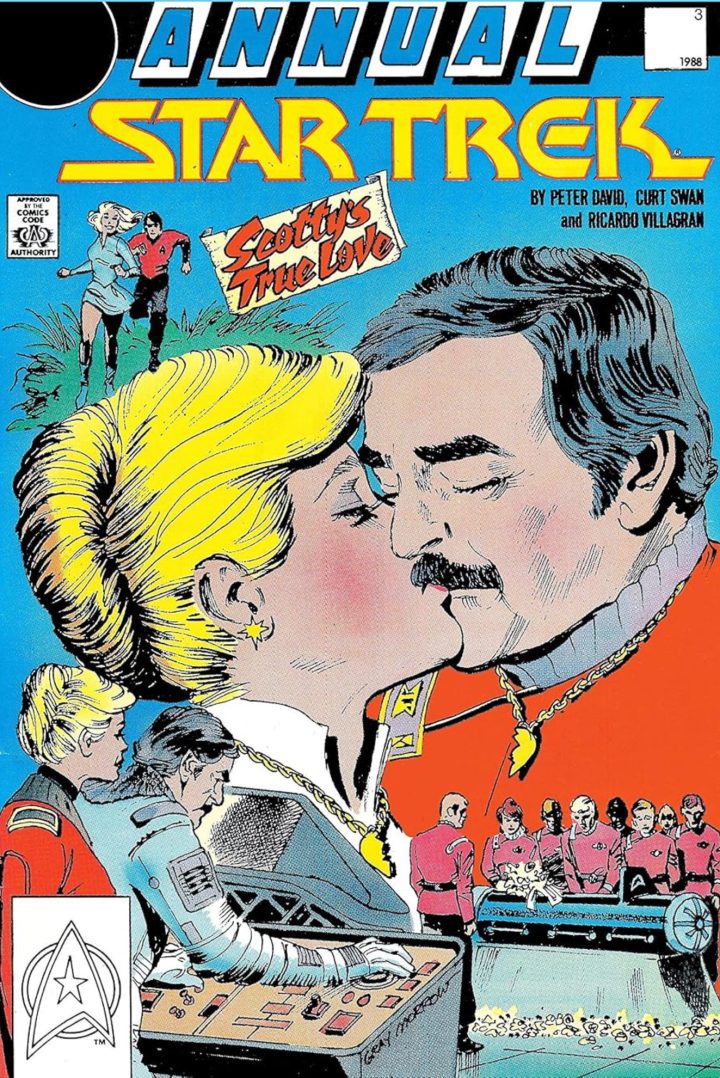

Star Trek Annual #3 (DC/IDW, 1988), written by Peter David, art by Gray Morrow

Star Trek Annual #3 (DC/IDW, 1988), written by Peter David, art by Gray MorrowBut no matter. David still had his staff job in the marketing department, but pretty soon he wouldn’t need it. Within a year of his firing from Peter Parker, David was making a living as a full-time freelancer. Almost immediately, any attempt to fully capture the range of his work becomes a fool’s errand: David’s output was almost implausibly prolific, encompassing not only freelance writing for nearly every major comic publisher in turn, but also licensed paperback novels (David was a longtime hand on the Star Trek franchise); original prose fiction; episodes of the Ben 10 and Young Justice animated series; live action scripts for Babylon 5; editorial columns; instructional books; and self-published memoirs. If genius were a game of numbers, David would have been unquestioningly in the first rank.

What set David apart, then and in retrospect, was the haunting sense that it never was just about the numbers for him. Robert Greenberger had been the inadvertent cause of David’s entering the comics industry, and in 1987 he was the proximate reason that David was able to go freelance, having offered him the assignment of the Star Trek comic series at DC where Greenberger had become an editor.

“Peter’s style varied,” Greenberger says. “He could really play into jokes and humor - that’s great because he sees the humor in the characters. But then he did the deadly serious stuff, and all the psychological stuff for Hulk or the quasi-religious stuff he did with Supergirl.”

David, in the introduction to one of his Star Trek novels, explained it this way: “I generally write two types of Star Trek stories. The first is your more standard type of adventure…The second is the more ambitious novel, in which I endeavor to look at the long history of Star Trek and try to tell a story that weaves together various threads and adds to the concept of Trek as a vast and infinite tapestry. Some fans love this sort of story, while others declare it to be ‘fannish’...which is odd, since I write all my books for myself and I am a fan.”

This, buried in introductory text to a prose novel, is as close to a confession of his modus operandi as David ever came. For all his veneer of winking irony, and all his knowing humor about the absurdity of pop genre fiction and its fans, David was himself a member of the club. If he could sneer at it, it was only to a point, and only with an affection that he couldn’t fully escape.

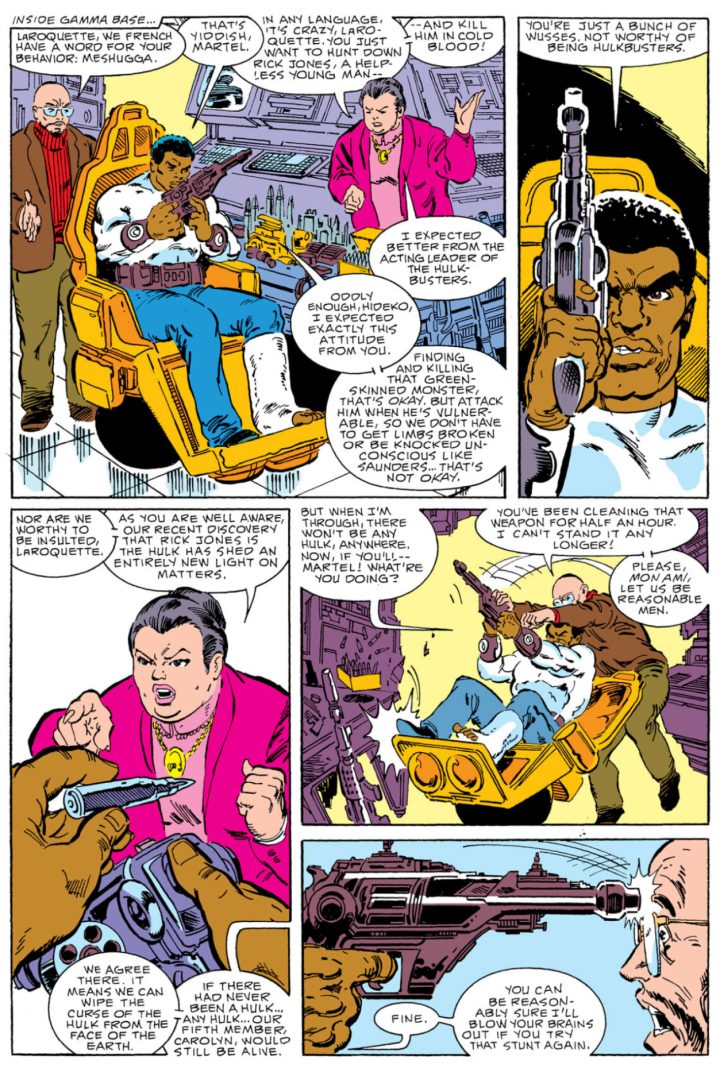

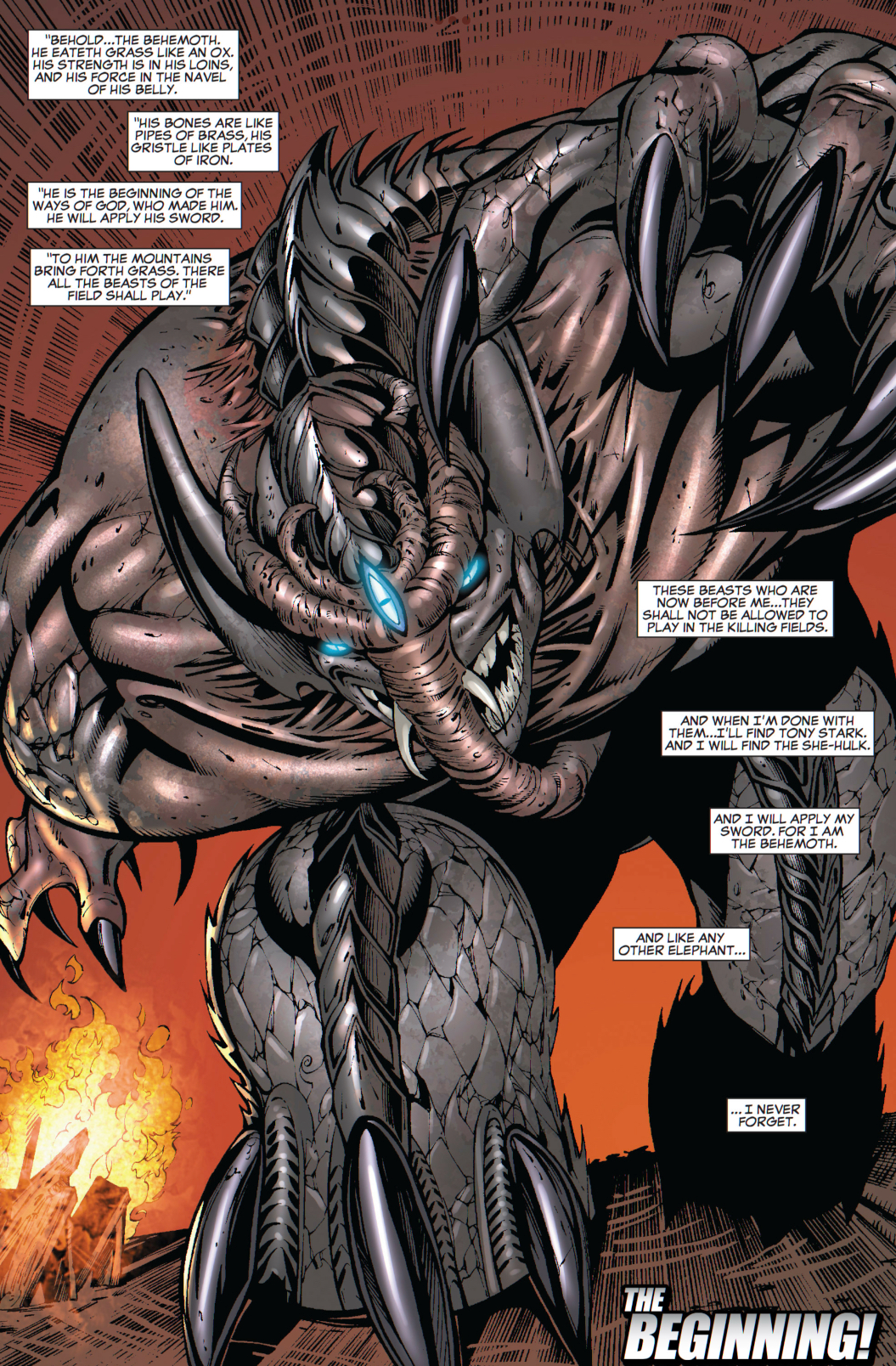

David’s hallmark series, and the one to which his legacy became inescapably tied, was The Incredible Hulk, which he took up the same year he left his staff position at Marvel. The run, which would last a full decade, was a bravura performance of skilful fandom: a remixing and reinterpretation of past history and lore that produced what felt, at the time, like a distinctively modern superhero comic. In a series formerly defined by rote reliance on a Hulk-smash status quo, David delighted in keeping his own fans off-balance, periodically upending the premise and characterization at center of the series whenever things threatened to become a little too comfortable: now the Hulk is a Las Vegas mobster in a three-piece suit; now he is merging elements of multiple personalities into a new professorial gestalt; now he is leading a would-be world government alongside a secret race that may or may not be Greek gods. This was clearly a writer who feared nothing more than becoming predictable.

That much was pure professional craft; the Peter David who was a veteran of Carol Kalish’s sales department. But there was a darker element, too, and it permeated the entirety of David’s long run. David’s first issue of The Incredible Hulk begins with the title character’s alter ego Bruce Banner standing alone in a desert, contemplating the possibility of suicide. His last story (in character chronology, anyway), the deeply unsettling Incredible Hulk: The End finds him again alone in a postapocalyptic wasteland, forever trying to end his life to escape the curse of his monstrous form, and forever failing to do it. In between, the changes of the title are marked by memorable sequences of loss and fear: the death of long-forgotten sidekick Jim Wilson from AIDS, a first in Marvel Comics; a protagonist struggling vainly to hold back the return of the savage beast locked in a literal door in his own mind; the Hulk returning to the site of his own creation to kill a future version of himself. Here is the superhero comic as metanarrative of the cyclical trap of the superhero comic: our own joy as fans and readers coming from the suffering of the characters as they must play out the beats of their origin again and again.

David with Fivish Finkle. Photo by Kathleen David

David with Fivish Finkle. Photo by Kathleen DavidBobbie Chase was David’s editor for the bulk of his time on Hulk, and it was she more than anyone who was responsible for pairing David with a remarkably talented string of artists over the course of his tenure (including, among others, Todd McFarlane, Dale Keown, and Gary Frank, all of whom vaulted from the run into 90’s hot-artist stardom that could eclipse David’s own). For Chase, like other editors who worked with him over the decades, David’s essential quality was his reliability: in a decade when the average Marvel comic was more notable for the quantity of foil and acetate in its cover than any of its literary content, David was unfailingly an oasis of solid readability.

“There was only so much you could do with the Hulk,” Chase says. “It's like Wonder Woman at DC. You don't necessarily want the icons. And Hulk was really hard at the time because he was just big, green, and dumb. How do you make stories about such a surface level character? So nobody cared beyond editorial what Peter was going to do. Gray Hulk, smart Hulk. If the book had been a really great seller and Peter had wanted to rock the boat, we might've gotten some pushback, but at the time it was just like, ‘yes, just do something with this character. Something needs to get done.’”

While David was building a following for his character, he was also building a following for himself – an unusual accomplishment for a writer in a decade of celebrity artists. It was very much by design. In 1990, he began writing a column, “But I Digress…”, for the Comics Buyer’s Guide. Modeling himself on his idol-turned-friend Harlan Ellison, David used the platform as a means of courting benign controversy, to the delight of readers and the fan press, though not always his employers at Marvel and DC. [Quote from Maggie Thompson]

In 1992, Peter David the character came to overshadow Peter David the craftsman. Todd McFarlane had once been David’s collaborator on The Incredible Hulk, but in 1991 he bolted Marvel with great fanfare to form Image Comics. David, from the perch of his weekly column, did his level best to stifle the enthusiasm, accusing McFarlane and his co-founders of repeating the same ideas in which they had trafficked at Marvel while claiming to be pioneers of a new breed of comics. Soon enough, a feud broke out, and just ahead of the 1993 Comicfest Convention in Philadelphia, McFarlane challenged David to bring the fight out in the open with a public debate. David the showman was all too happy to oblige.

“Well, thank God that’s over,” David wrote in his column the week after the debate took place. David had come, dressed in coat and tie, with index cards prepared for every eventuality of debate: well-rehearsed, well-prepared, and expecting to demolish McFarlane with quotes drawn from the artist’s own past statements to the press. McFarlane arrived shirtless and in boxer shorts, wrapped in a towel like a fighter entering the ring. He had prepared nothing, and took no question seriously. The overall effect was like two wrestlers who had each come prepared for a kayfabe match, but forgotten to coordinate their acts in advance – David the high school debate team captain charging, inexplicably, at Ridgemont High’s Jeff Spicoli.

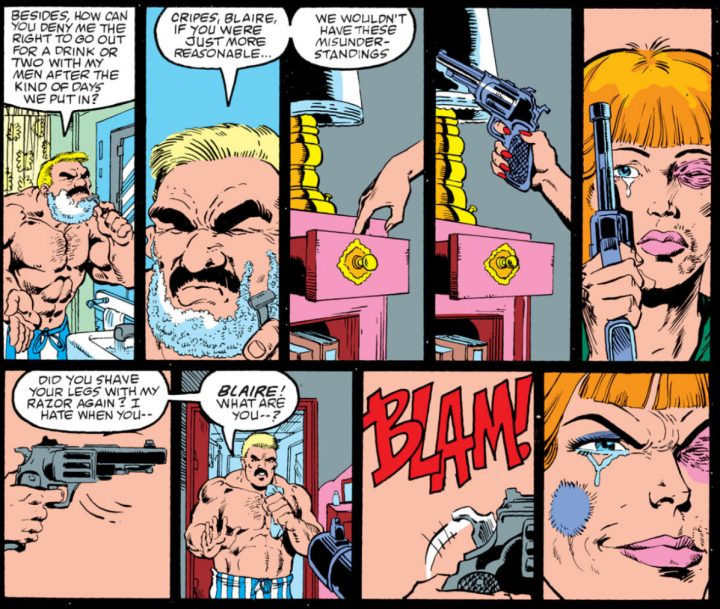

Panels from "Quality of Life" (Marvel, 1987) written by Peter David, pencils by Todd McFarlane, inks by Rick Parker)

Panels from "Quality of Life" (Marvel, 1987) written by Peter David, pencils by Todd McFarlane, inks by Rick Parker)“I’m told Peter literally spent the train ride to Philadelphia rehearsing,” says Bob Greenberger, who was in the audience that day. “Peter comes in, this guy has note cards, he's dressed and ready for a debate. Todd comes in with his boxing robe and the Rocky music, and whatever. And after one or two questions, Todd clearly was winging it. And then when Peter gave that long speech, equating Todd to Switzerland,Todd just gave in, and the audience was in stitches. Peter ran rhetorical rings around Todd, who thought he was going to be there for some fun, and wasn't prepared for a real bad day.”

The crowd laughed, and the judges gave David the victory with a 2-1 vote, but a curious thing happened as the event filtered through the rumor mill to fannish circles and the nascent world of online message boards: David started to look like the bad guy. From a distance, it turned out, the carefree, shirtless boxer looked a whole lot more sympathetic than the overprepared valedictorian. It was jocks vs. nerds writ large, and the world of 1990’s comics was, stereotypes notwithstanding, no place for nerds.

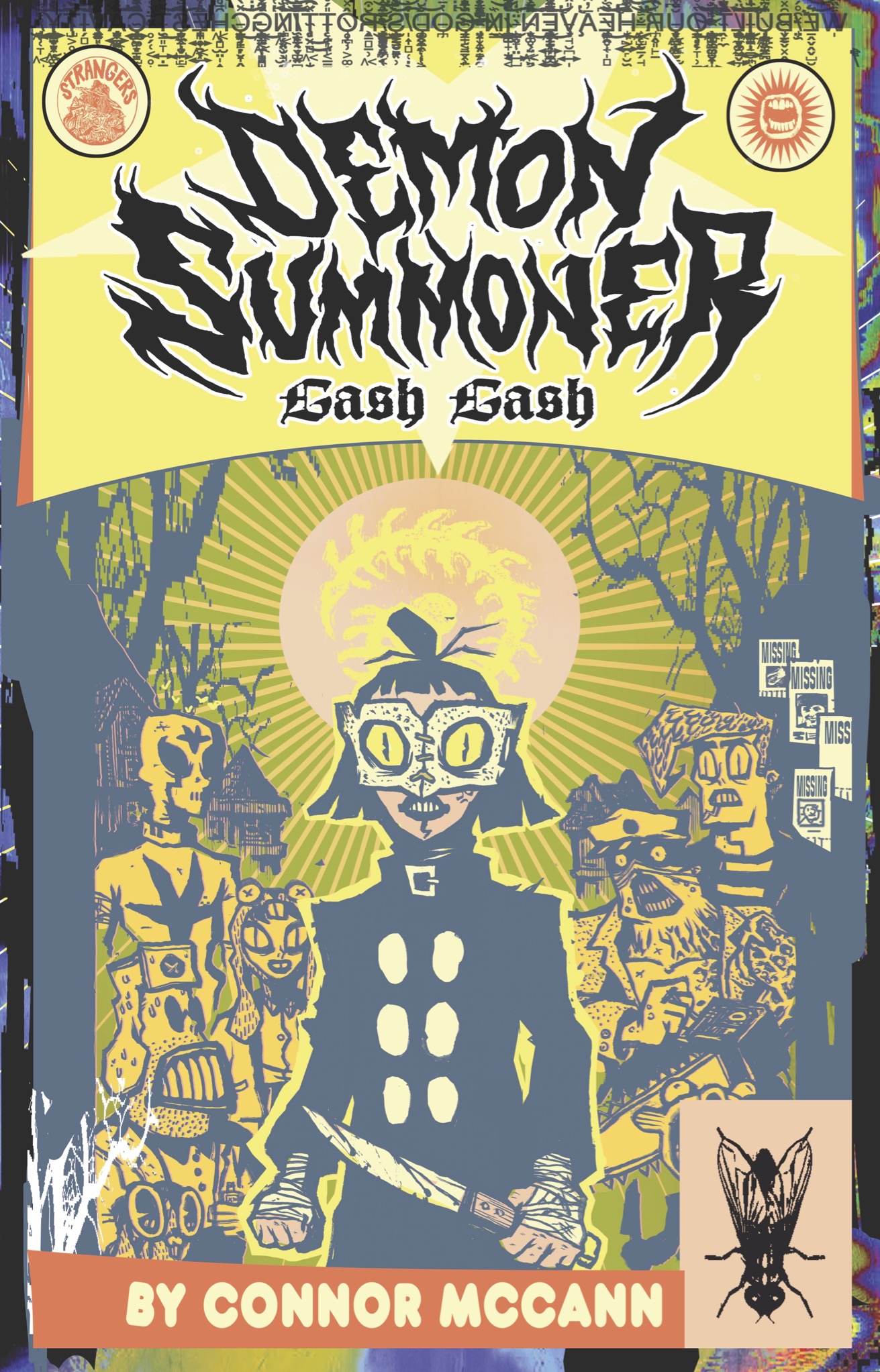

It would be very wrong to reduce Peter David’s biography at this point to a series of high-profile public feuds and controversies. Paramount, after all, were the comics David was writing: not only the Hulk, but Aquaman and Young Justice for DC, X-Factor and Spider-Man 2099 for Marvel, a smattering of creator-owned titles for various independent publishers, and vastly more one-shots and miniseries than would be feasible to enumerate.

The quality or the quantity of his work was never the problem: it was just that, more and more, the hoopla surrounding it started to become just as prominent. This was partly by design – David was, as ever, an incorrigible hype-man – but not always. His stint on the Star Trek comic ended ugly, with a simmering feud with Gene Roddenberry’s representative Richard Arnold at Paramount. His long run on Hulk ended uglier still: when Marvel insisted that David’s decades of character evolution be undone in favor of a more media-friendly status quo, David walked from both the title and the company. His bleak, grim final storylines for the comic (in which the Hulk’s wife Betty dies of radiation poisoning, and the Hulk himself is hunted into isolation) reflect the frustration of the moment, and are bracing to read even now.

Panels from "Dance with the Devil!" (Marvel, 1987) written by Peter David, pencils by Todd McFarlane, inks by Fred Fredricks

Panels from "Dance with the Devil!" (Marvel, 1987) written by Peter David, pencils by Todd McFarlane, inks by Fred FredricksIn 1999, he was enticed back to Marvel to helm a rebooting of the publisher’s Captain Marvel title. The book was a solid seller, if not a blockbuster, but a year later the company underwent a major change in editorial leadership with the arrival of Vice President Bill Jemas and Editor in Chief Joe Quesada, who jointly spearheaded a move toward an edgier, hipper, and more modern brand of superhero comics. For Jemas especially, David became a kind of bête noir; a living embodiment of the fan-centric, continuity-laden comics that the new Marvel was meant to escape.

When David complained in his “But I Digress…” column about a price hike on lower-selling Marvel comics, the gauntlet was thrown. Jemas’s brainchild was the U-Decide campaign: David, Jemas, and a third entrant (Ron Zimmerman, something of a hapless bystander in the affair) would go head-to-head with new series that they would each write. The winner, a la Glengarry Glen Ross, would get to keep being published. The loser would take a pie in the face in public.

It was a publicity campaign in good fun, but only up to a point: for a freelance writer, there was something genuine at stake. It was also, symbolically, a tug-of-war: Peter David and the fandom of comics past; Bill Jemas with the flash and sizzle of comics future. “Bill was a jock and Peter was a geek,” says Tom Brevoort, David’s editor on Captain Marvel. “As day follows night, there was a basic lack of empathy or respect there. And Bill was certainly prone to being, I’ll say, theatrical, publicly.”

So, however, was David. On a promotional conference call with comics retailers in which all the U-Decide competitors pitched their books, David fired off his coup de grace. “One by one down the line, each of the three of them sold their book,” Brevoort says. “And the call got done, and Bill and Joe high-five one another because they were like, ‘We totally smoked that guy. He came off as such a lunatic and a loser, and we are the geniuses of the world.’ And then a week later, coverage started to come out and all the coverage was like, ‘This new Captain Marvel book sounds great!’” Peter David, sales and marketing professional, had staged his comeback special.

At one point during the competition, Brevoort was talking to David on the phone. He recalls: “I said to him, ‘Peter, if I were you, I would just quit and walk away, because this game is rigged. They run the table, you're playing against the house, there's no winning here. Even if they lose, they're just going to say they won and do whatever they want. What the fuck are you doing?’

“And he basically said to me, “Look, they're paying me to write this book and I like to write it. And as long as they're doing that, I'm going to stick it out. I'm going to do it.’ And ultimately, everybody reneged. Nobody went in a dunk tank, and nobody got a pie in the face. They just stopped talking about it after it was clear that this contest wasn't going to go the way that Bill had hoped. And the end result is we got 25 more issues of Captain Marvel.”

It was a personal victory, albeit something of a pyrrhic one. David would remain on a Marvel contract for almost the rest of his life, but much of that time was spent in private corners of the Marvel publishing line, stewarding long-running books with cult followings (like the sturdy X-Factor) but little of the media zeitgeist of old. When David did make news, it wasn’t always for the right reasons. In 2016, a panel at the New York Comic Con on LGBTQ representation became a fiasco when David was confronted by a question from activist and educator Vicente Rodriguez about the representation of Roma characters in comics.

David’s response was shocking by any standards: an extended tirade laced with stereotypes and offensive canards about Romani culture that seemed to stun both the panel and the audience into silence. By that evening, the response in the comics press was brutal: “Anti-Romani statements made at X-MEN LGBTQ Panel,” reported Elana Levin, who had been present at the panel. “Peter David Talks to Bleeding Cool About *That* New York Comic Con Panel,” wrote Rich Johnston.

In less than a week, David had issued an extensive mea culpa on his website, writing, “I have to conclude I’m ashamed of myself.” But the damage was done. David, who had won a GLAAD Media Award in 2011, had always prided himself on his left-leaning politics. Now, it seemed, he had starkly revealed his limitations. Today, Rodriguez is still unconvinced by David’s apology. “I don’t believe the apology was sincere at all,” he says. “He did this because somebody [at Marvel] gave him a talking-to, but he didn’t mean it. It’s really an interesting case, because you have somebody that was obviously so intelligent, so smart, and so sophisticated in his talk about minorities and history, and suddenly he was unable to show any empathy for this group of people that are the largest minority in Europe.”

David with Bob Greenberger, Will Smith, and Mike Friedman, photo courtesy of Bob Greenberger

David with Bob Greenberger, Will Smith, and Mike Friedman, photo courtesy of Bob GreenbergerPerhaps history was outpacing David again. During the last decade of his life, he continued to write regularly for Marvel, but almost exclusively for short-run series reviving his hits of the past. “All of a sudden he had fallen out of mainstream Marvel and mainstream DC,” Robert Greenberger says. “If you look at the last handful of stuff he had written before he got sick this last time, they were the nostalgia acts, more stories of the Gray Hulk and more stories of the Maestro. And I have to give David Bogart at Marvel tremendous credit for sticking with him and keeping him under insurance under Disney.”

David’s home life was altogether less fraught. Shortly after his divorce in the late ‘90’s, David began dating Kathleen O’Shea, who frequented the same comic and sci-fi conventions at which David was a staple. The two were married in 2001, and by all accounts, the home life that ensued may have been the happiest David had known.

Unlike his first marriage, which had been strained under the pressure of David’s prodigious work habits, Shea was an active collaborator in David’s writing work, acting as a first reader, sounding board, and sometimes source of ideas. She recalls helping David craft the premise of his Madrox miniseries, which became the springboard of a decade-long run on a relaunched X-Factor: “Peter comes in and says, kind of in a grumpy voice, ‘They want me to write Madrox. He’s a guy who duplicates himself. How can you make that interesting?’ I said, ‘It's real easy. He's schizophrenic. Each dupe is an individual piece of his personality.’ And Peter went, ‘I can work with that.’” It was a warm relationship, and it would grow stronger during those last years when David’s health began to go.

In 2012, David experienced an ischemic stroke while returning from a trip to Florida, which for a time lost him the use of his right arm and leg, and part of his vision. He made a slow and difficult recovery, but in 2015 was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. The major blow, however, came in 2022, when it all seemed to fall apart at once: a series of rapid-fire strokes coincided with kidney failure, and left David hospitalized off and on for the remainder of his life. Kathleen launched a GoFundMe campaign on his behalf; it would remain open and posting periodic updates for the next three years.

Kathleen recalls that David’s initial response to the crisis was to try once again to recover by dint of writing. This time, as his health continued to give way, it was more difficult. “He went into rehab and it looked like he was going to have to walk with a walker for a while, but he was doing okay,” Kathleen David remembers. “And then his insurance ran out, and so they hurried the pace up to send him back home, which lasted for a grand total of 36 hours. And then he was back in the hospital…He desperately wanted to get out of there, and was always asking me, “When can I get out of here?’ And I would have to say to him, “Honey, you're not even close.’”

From the Shore Leave release panel celebrating the publication of They Keep Killing Glenn, co-edited by Peter & Kathleen. David, Peter, Aaron Rosenberg, me, Mike Friedman, Mary Fan, Russ Colchamiro, Kathleen David,. In the center: the not-quite-dead Glenn Hauman

From the Shore Leave release panel celebrating the publication of They Keep Killing Glenn, co-edited by Peter & Kathleen. David, Peter, Aaron Rosenberg, me, Mike Friedman, Mary Fan, Russ Colchamiro, Kathleen David,. In the center: the not-quite-dead Glenn HaumanFor someone like David, whose prodigious output had defined his work habits for five decades, the loss of his writing was a cruel blow. “He thought he could do it,” Robert Greenberger says. “It never seemed to take hold. As I understand it, he tried speech-to-text [software], but his illness left him with a bit of a slur in his speech that the text function just could not pick up, and it got frustrating. So he stopped.” He died on May 24, age 68, more published credits to his name than it would be possible to reliably count.

And will we remember Peter David? His friends think so. “He is what people should aspire to be,” says David’s friend and editor at the Comics Buyer’s Guide Maggie Thompson. “Creative, kind, generous, thoughtful, articulate. It's creative and practical. The combination of working through challenges to get the best possible result.”

“A really brilliant, volatile, funny, deeply talented guy,” says Colleen Doran, another of David’s collaborators and friends. “His heart was in the right place. I knew he had his detractors because he could just say shit. He had no filters, but his heart was always in the right place. I think he was essentially a good person.”

“His 12 years on the Hulk earns him memory because he did things that had not been done before with the character that have resonated and lasted,” Greenberger says. “The Maestro is a character creation that endures at Marvel. So yeah, I think that body of work alone earns him memory. But the larger career as a novelist, animation writer, live action writer, comics writer, and all that versatility is rare among writers in our field, and that should be celebrated.”

David was a kind of comic professional that almost seems quaint now: month after month, with clockwork dependability, producing a story that would entertain you, no questions asked. Beneath the feuds, and scandals, and the sad final days, that much remains true. In one of his more famous Hulk stories, an alien named Talos the Tamed challenges the Hulk to a fight in order to regain his honor, only to fail in his goal of dying in battle. Returning to his fellow Skrulls, he is prepared for disgrace. Instead, they tell him: “You…fought the good fight. What more can any Skrull do…”

And Talos the Tamed replies, “What indeed.”

English (US) ·

English (US) ·