Brian Nicholson | September 18, 2025

Once there was a publisher by the name of Slave Labor Graphics. That name wouldn’t fly these days, but for 25 years, cartoonists accepted it on the basis of it being unrepresentative of their payment practices. At least by Evan Dorkin’s account, they paid a greater royalty on reprints (60%) than anyone does now. Dorkin was one of many cartoonists — including Derf Backderf, Jim Rugg, and Bernie Mireault — who worked with the publisher at the beginning of their careers. That list does not include any of the women — such as Megan Kelso, Rebecca Dart, and Jessica Abel — published in Sarah Dyer’s anthology Action Girl Comics, surely an important part of the company’s contribution to comics history. We can consign to the dustbin of trendhopping pandering such titles as Attitude Lad, Slacker Comics, and Emo Boy; works which might’ve gotten the house dismissed as corny by their peers at the time. Still, people do not really talk about Slave Labor in terms of their legacy, or consider their output as a collective whole.

Perhaps it is my bias towards self-preservation as a critic that thinks it probably helps a publisher if they have a critical apparatus attached to them, if not to write their hagiography, then to at least explain what it is they’re trying to do. Fantagraphics had The Comics Journal to contextualize the work they published within a broader context of comics history, arguing that Los Bros Hernandez were artists the equal of Cliff Sterrett, thus paving the way to later handle reprint projects for Charles Schulz and Carl Barks. More recently, Strangers offered a sort of post-Bubbles take on the fanzine to cover a Cartoonist Kayfabe-approved vision of genre comics, establishing expectations for what Eddie Raymond was interested in once they began publishing comics. For a brief time, Slave Labor published the magazine Destroy All Comics which offered a window into the world of Bay Area minicomics, but the perspective of editor Jeff Levine was not indicative of the company as a whole. While they were tied to the Bay Area, and were one of the major sponsors of the now-defunct APE, the Alternative Press Expo, if you were not from the area, you wouldn’t necessarily think of them as Californian.

Most likely you think of them as goth. Goth in a different way than that of Caliber Press and The Crow. Slave Labor was mall-goth, for those not old enough to get a tattoo yet. Caliber’s work was characterized by tendencies to intricately delineated ink work vs. Slave Labor’s brute outlines. Evan Dorkin wasn’t goth, but with features like Milk And Cheese, the Devil Puppet, the Murder Family, and strips that appeared in a comic book adaptation of the zine Murder Can Be Fun, he showed you didn’t have to be goth to revel in the quasi-comedic potential of naked misanthropy. But while Dorkin placed upon the covers of Pirate Corp$ the telltale two-tone checkers of ska fandom, the breakout hit cartoonist of Slave Labor Graphics was Jhonen Vasquez, and he wore a Skinny Puppy tee.

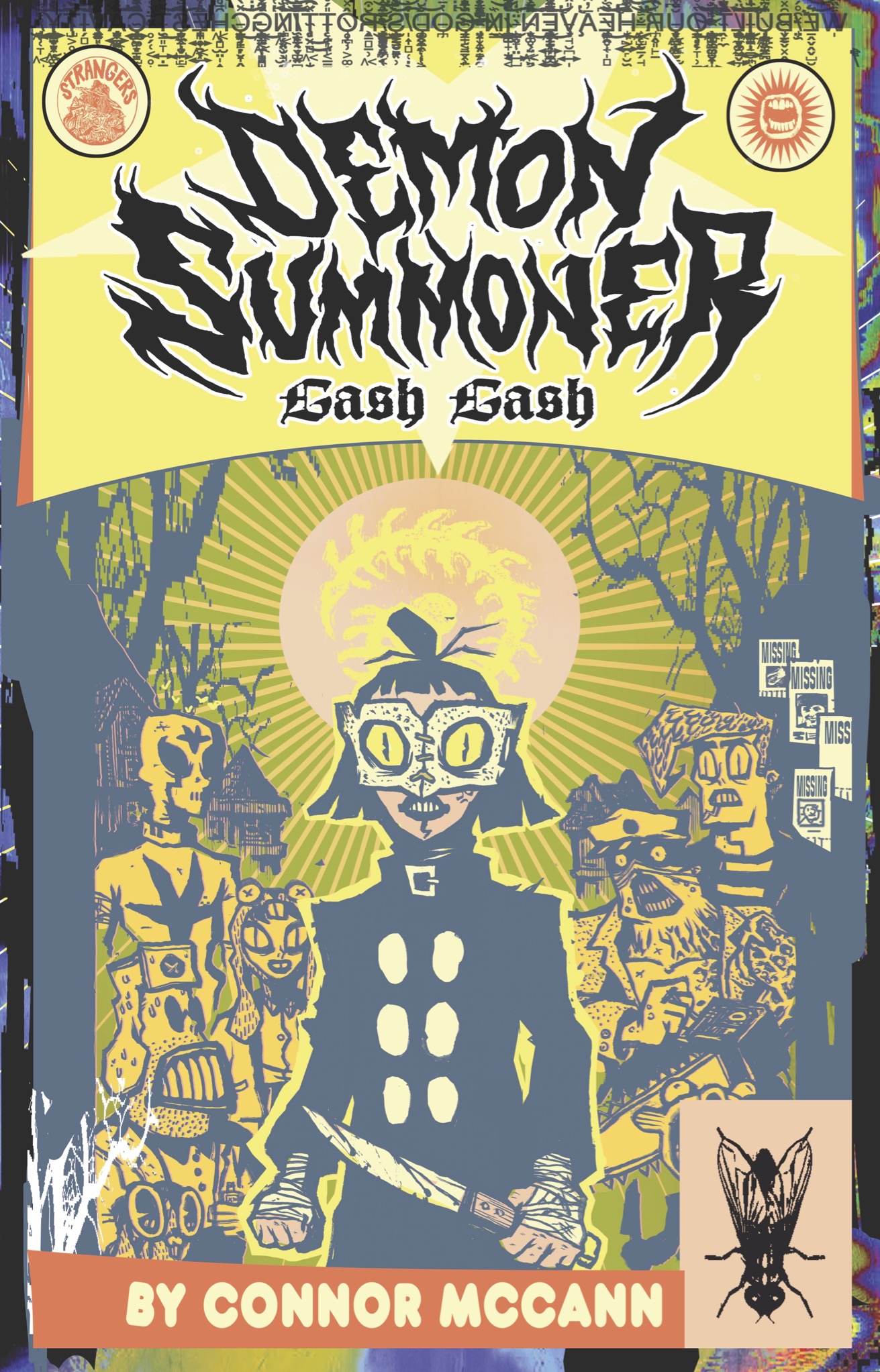

I could not read Connor McCann’s Demon Summoner Gash Gash, newly published by Strangers, without thinking of Vasquez’s Johnny The Homicidal Maniac. Listed on his back cover are his chosen reference points: Devilman, Cormac McCarthy, and Gummo; and to all that I say, “Get the fuck out of here if you’re trying to act like you weren’t wearing a JTHM shirt at least once a week for a full year of high school.” Look at the front cover, with the buckle around the main character’s neck, and the long stabby knife streaked with blood made of the same marks as the bandages wrapped around the hand that grips its hilt.

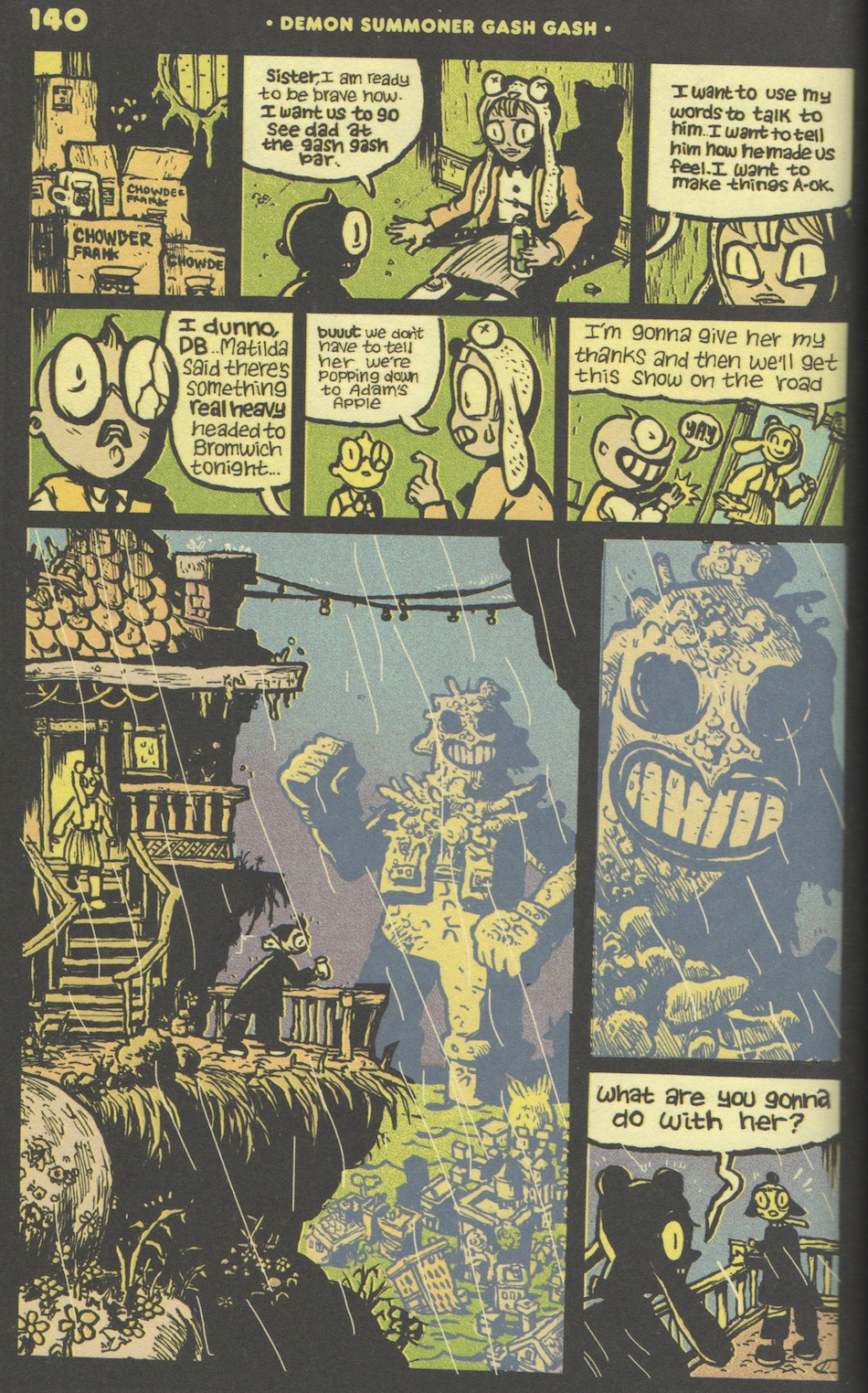

But while I presume to know the backstory of the artist’s youth, I could not infer the supernatural lore that serves as the backdrop of this comic, the metaphysics of the hellscape from which the titular demons are summoned. "Gash Gash" seems not to refer an onomatopoeia of stabbing and bloodletting. People in the town of Bromwich Bay, we are told in an opening bit of exposition, kill each other in the name of Gash Gash. This seems like the belief system of all the inhabitants of the book’s world but our protagonists are also outcasts bullied in their youth for being freaks; the whole thing is extremely goth-coded. McCann doesn’t delight in drawing his enemies receiving their ruin in violent fates. Times have changed and we’re too depressed for that. The humor is one of a deadpan stoicism. While there is the wish-fulfillment of being a powerful witch, it is still a world where more malignant forces lurk.

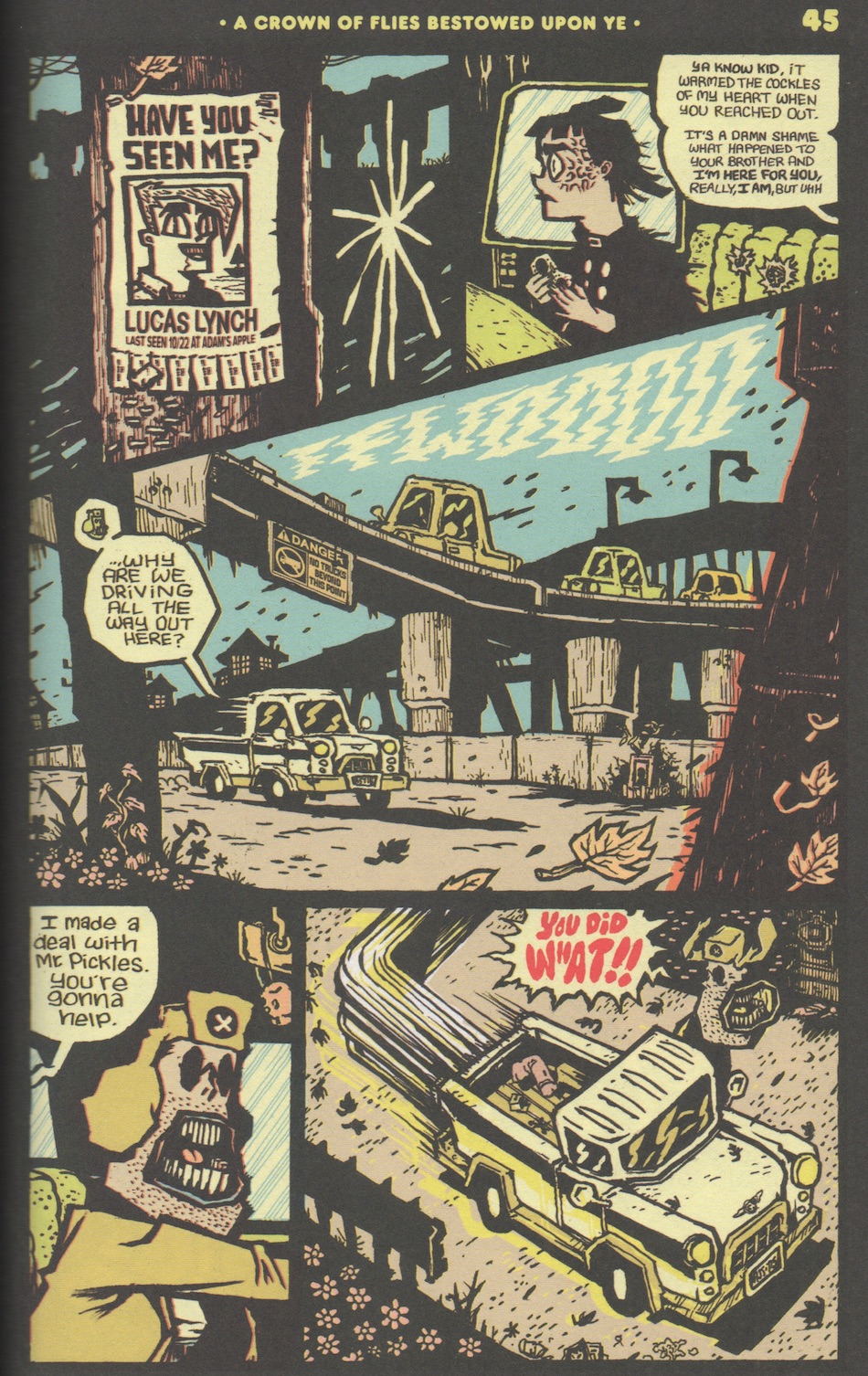

Demon Summoner Gash Gash is split up into chapters, with bits of ancillary material that suggest the book collects four issues of a series I missed the serialization of. Perhaps it was digital-only, that would explain a lot. The repetition in the title is explained by McCann being, as all cartoonists should be, a fan of alliteration. The town is called Bromwich Bay, the two leads are siblings Matilda and Mason Marrow. The school they don’t attend is called Harrow Hill. It is comic book magic that alliteration is the way you make both a hook and a worm.

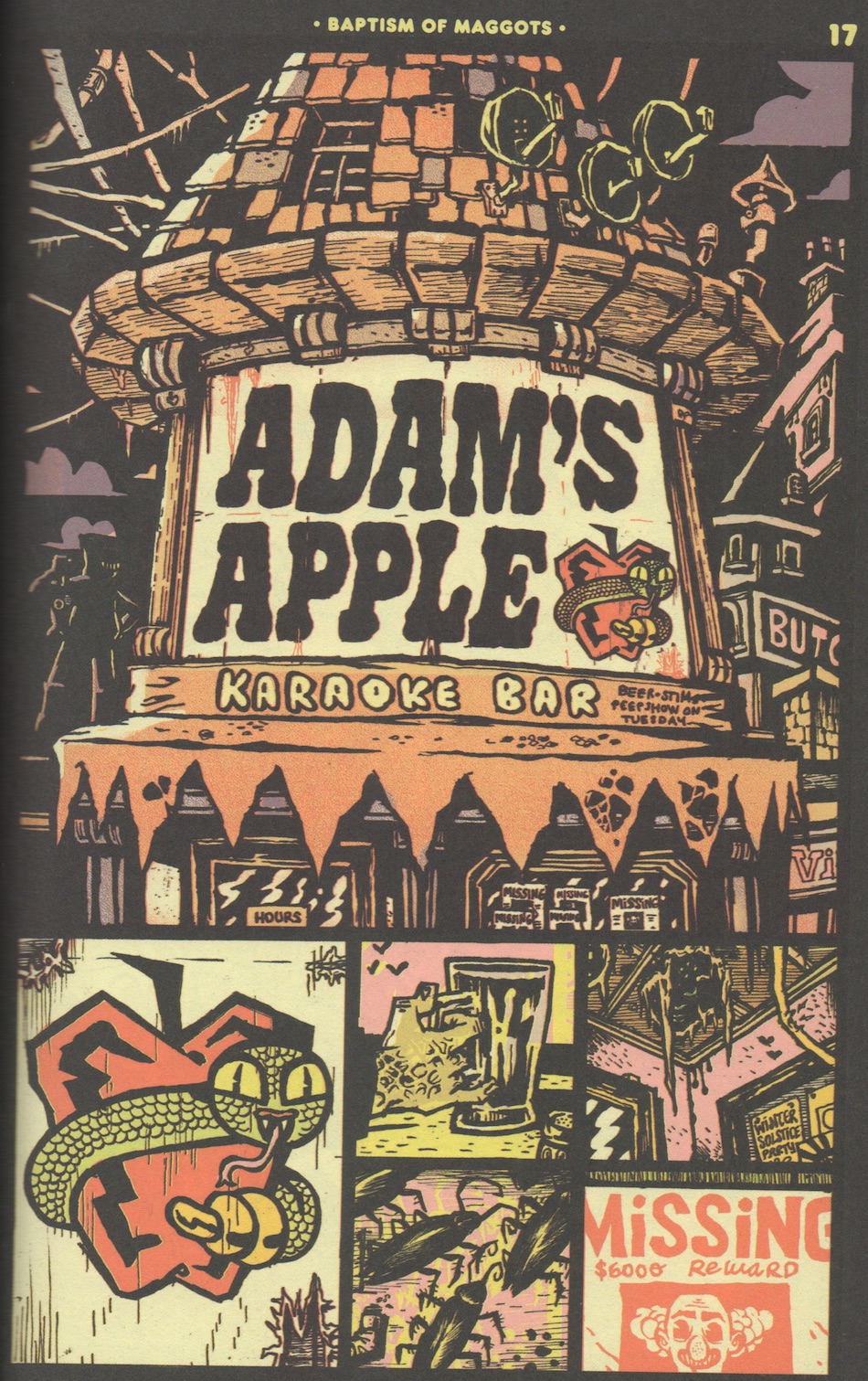

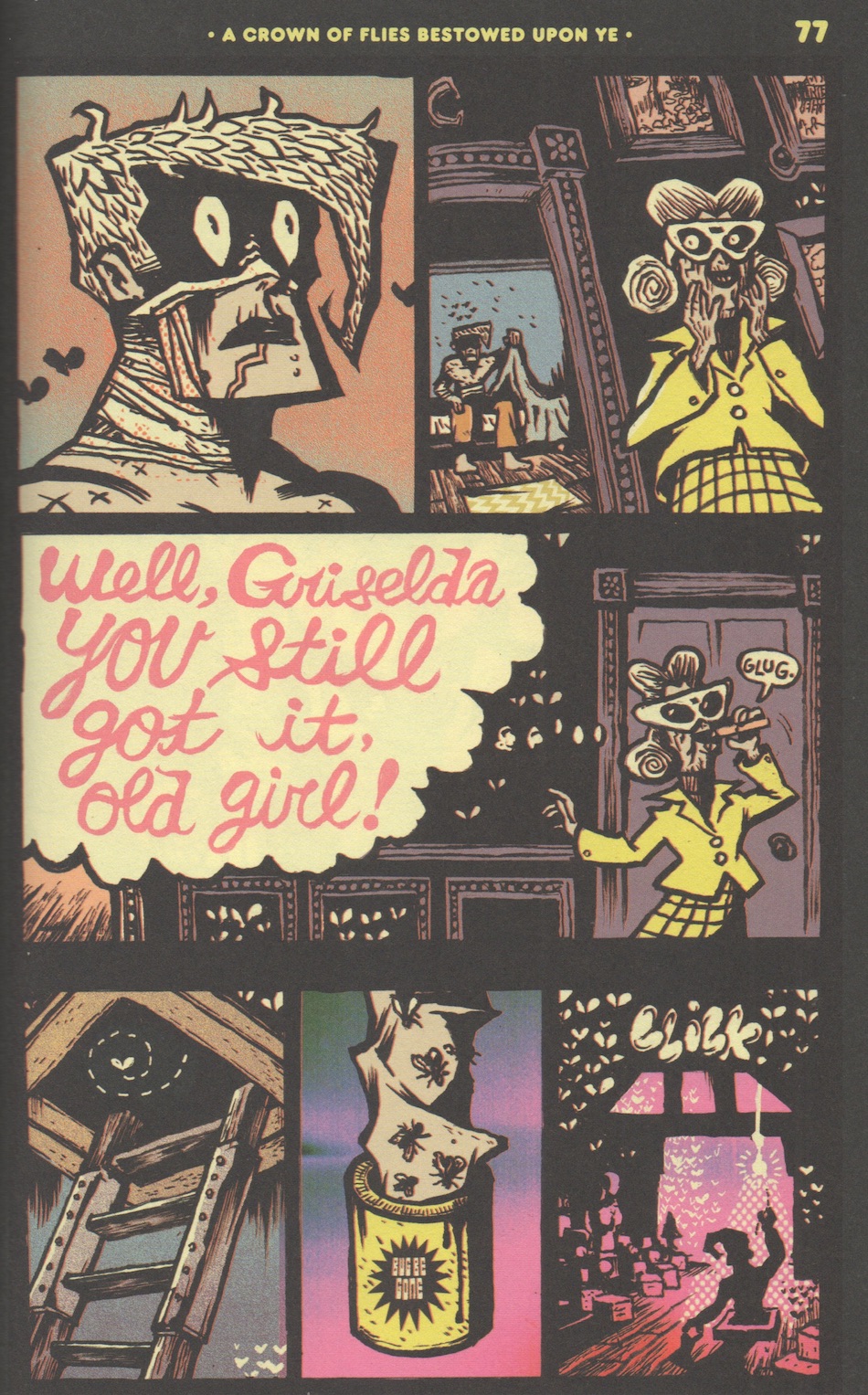

McCann slashes his black ink onto the page with little spermy squiggles coming off the edges of oversized lettering. Slave Labor and Caliber Press were both black-and-white publishers, a financial decision of the era today’s cartoonists need not reckon with. McCann’s color sense, strong and simple, corresponds to standard printmaking. McCann is a RISD alum, and some might want to connect the frenetic linework, genre overtones, and metal-adjacent demonic invocations to Fort Thunder’s comics made by noise rockers. However, the comics of that crew are marked by a sense of moment to moment storytelling to move a figure through the physical space of a page, and it is perhaps the greatest mark against McCann’s comics that they do not do that. Far too many pages feel dominated by design elements rather than reading in terms of fluid motion. Pages are bordered in black, with the subtitle of the “issue” displayed at the top to remind the reader of it, a decision I have not seen in any other comic, likely because it is so purely distracting.

Maybe it is the influence of black metal band logo lettering that makes McCann choose to make his lettering so prominent. It is not a question of there being too much dialogue on the page, but a tendency to make pages look like they’re title pages, occasioned by a stray bit of verbiage, a sense that a phrase could be evocative, and the best way to make that known is to plaster it. It is likely just a coincidence that the font used on page 160 for the name Matilda Morrow is the same font used on the logo of Gregory Benton’s Hummingbird, published in 1996 by Slave Labor, but if McCann hasn’t read that comic he would like it. It’s the story of a young girl whose mom has a mental breakdown, making any point Demon Summoner Gash Gash may have wanted to make about facing chaos with real world referents rather than elaborate fantasy. While Demon Summoner offers up the refrain “Everything eats and must be eaten” — as a line of dialogue early on then writing it in huge lettering and spreading it across six pages at the book’s climax — Benton begins his story with a mentally ill woman biting into a house cat and later gives us a dream sequence where a car is filled with entrails, showing instead of telling. Both comics also engage in similar graphic design techniques in terms of digital borders and fonts, but with Benton having as an excuse that it was 1996, the year McCann was born.

For all of the popularity of Johnny The Homicidal Maniac, all the sales made at Hot Topic franchises nationwide, Vasquez’s Nickelodeon series Invader Zim found a larger and younger audience. There is a heavy animation influence to McCann’s art, and this too is part of the Slave Labor legacy. Few titles suggest the sense of humor of their era quite like Life Of A Fetus, created by Andy Ristaino, a future Adventure Time staffer whose approach to composition suggests he's a clear predecessor to McCann. Years before that, Ristaino’s fan art of The Maxx got printed on an issue’s back cover — all of these things are part of a tapestry: To stop the tears streaking mascara in a mall from disappearing like tears in the rain they must be preserved in a history like this.

McCann’s overly designed approach perhaps works if the reader grants the grace to perceive the page as a storyboard: When an elaborate sign, in the foreground on the left of a panel, is dwelt upon for long enough we can see the right side of the image, with its greater depth, as the would-be continuation of a pan in a television-sized frame. The reader must move through the page to see the world, it does not feel like the characters are moving and you are following them through it. This world is pleasingly jagged and ramshackle, and the viewer often alights onto a close-up of a face: Sweat-streaked, veins throbbing, wrinkled, pustule-ridden. Teeth are almost always visible, except when you are meant to know someone is pursing their lips in upset. You can see the big eyes as a Cartoon Network stylization, kin to Dexter’s Laboratory and The Powerpuff Girls, but they are also bulging out, the same way the teeth do, the same way the landscape swells with putrescence.

For all the book’s irreligiousness, I must conclude on a note of confession: I have never actually read Johnny The Homicidal Maniac, nor have I ever seen an episode of Invader Zim. I could say they passed me by, if that wouldn’t imply I hadn’t been aware enough of their existence to avoid them deliberately, knowing they were not for me. You could know the deal without deep investigation. When I make this comparison to a thing I admittedly know nothing about, I do have to offer the disclaimer of my ignorance, but I do not have to couch that comparison in an admission of its lesser light. There are so many comics about which I can say “It is doing a modern version of a thing that existed thirty years ago” I nonetheless believe could never mean as much to a young audience as its predecessor did, and so must interpret it as a nostalgia act for a dwindling audience. It is hard for me to imagine any of the quasi-independent genre comics coming out from the likes of Image or Boom today ever hitting readers as hard as Grendel or Preacher would have in their respective eras, for instance. I have read those comics, and knowing how their myriad strengths translate to emotional investment, I know they exceed expectations. Not being as familiar with the appeal of Johnny The Homicidal Maniac, I can imagine Demon Summoner Gash Gash hitting its marks with ease. I would assume it has greater narrative construction: Even as I was confused as to what exactly was happening and why, it seemed like a lot was going on. Demon Summoner Gash Gash is something I can in good faith recommend to people who like things I do not. Many of the stylistic decisions I object to in this book are present in the work of Juni Ba, for example. McCann’s work does not feel like it’s written for children, nor is it transparently digitally drawn to an off-putting degree, but both cartoonists make work that strikes me as over-designed. It seems likely McCann likes comics I also enjoy. Richard Sala, while too cool for Slave Labor, was a Bay Area cartoonist, and you can see in McCann’s work that if you took the cute girls and nebbishes out of Sala’s giallo homages you’d arrive at something with more of a Rob Zombie vibe. I do mean this in a derogatory way; that’s why it’s good to keep that stuff in there.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·